HIGHLIGHTS

Globally – 25 years

• In the past 25 years, the

overall percentage of

women in parliaments

has more than doubled,

reaching 24.9 per cent

in 2020, up from 11.3 in

1995. In lower and single

houses of parliament, the

percentage of seats held

by women increased from

11.6 to 24.9 per cent. Upper

houses saw the percentage

increase from 9.4 to

24.6 per cent.

• In 1995, no parliament had

reached gender parity. In

2020, four countries have

at least 50 per cent women

in their lower or single

chambers, and one has

over 60 per cent of seats

held by women (Rwanda).

• There are countries in all

regions except Europe

that still have lower or

single parliamentary

chambers with less than

5 per cent women: three

in the Pacific, three in the

MENA region, one in the

Americas, one in Asia and

one in sub-Saharan Africa

– nine in total. In 1995, the

total was 52 such chambers

spanning all regions.

• Over a 25-year span, the

largest progress in women’s

representation has been

achieved by Rwanda, the

United Arab Emirates,

Andorra and Bolivia, with

+57 +50, +42.8 and + 42.3

,

percentage points gained

between 1995 and 2020,

respectively, in their lower

or single houses.

Women in parliament:

1995–2020

rs

ea ew

y i

25

rev

in

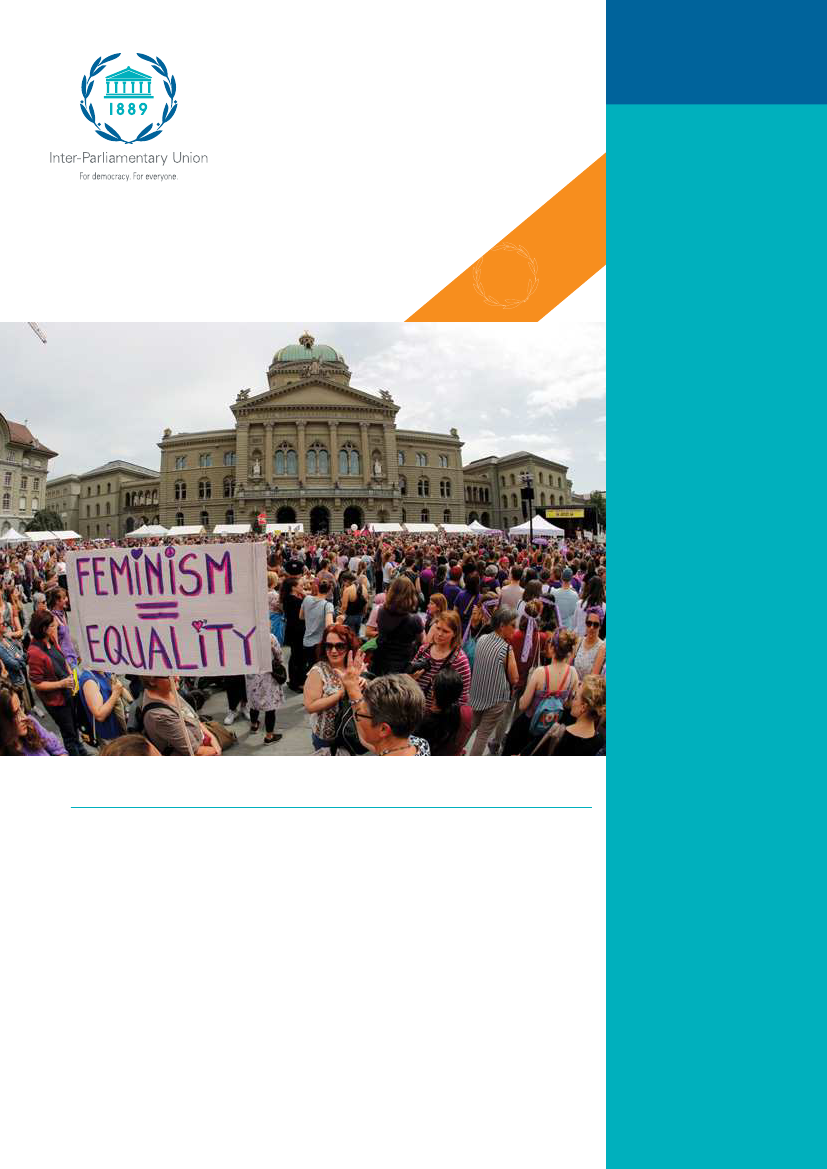

Women protest in front of the Swiss Parliament during a nationwide women’s strike for gender

equality on 14 June 2019. Elections later that year saw an unprecedented number of women elected to

parliament. © Stefan Wermuth/AFP

A quarter of a century after the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in

Beijing, expectations regarding women’s participation in politics have grown in ambition.

Achieving a critical mass of 30 per cent of seats held by women is no longer the objective.

Shifting the paradigm towards full equality has been the biggest achievement of the past 25

years. With such a bold goal ahead, active steps are needed to accelerate the change that will

lead to gender parity in parliaments.

The last 25 years have seen a significant increase in the proportion of women in parliaments

around the world. In 1995, just 11.3 per cent of seats held by parliamentarians were held by

women. By 2015, this figure had almost doubled to 22.1 per cent. And

although the pace

of progress has slowed in the past five years, in 2020, the share of women in national

parliaments is close to 25 per cent.