NATO's Parlamentariske Forsamling 2010-11 (1. samling)

NPA Alm.del Bilag 5

Offentligt

CIVIL DIMENSIONOF SECURITY208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1Original: French

NATO Parliamentary Assembly

SUB-COMMITTEE ONDEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE

THE WESTERN BALKANS, 15 YEARS AFTERDAYTON: ACHIEVEMENTS AND PROSPECTS

REPORTMARCANGEL (LUXEMBOURG)RAPPORTEUR

International Secretariat

19 November 2010

Assembly documents are available on its website, http://www.nato-pa.int

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

i

TABLE OF CONTENTSI.II.INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1ACHIEVEMENTS: TRANSCENDING CONFLICT TO BUILD A ZONE OF SHAREDSTABILITY AND PROSPERITY............................................................................................. 2A.ESTABLISHING A ZONE OF SECURITY AND STABILITY IN THE WESTERNBALKANS: FROM BLOODY ARMED CONFLICTS TO REFORM OF THE DEFENCEAND SECURITY SECTOR ........................................................................................... 2B.CONSOLIDATING INDEPENDENT STATES’ IDENTITY AND STRUCTURES............ 5C.PUNISHING THE GUILTY............................................................................................ 5D.DEVELOPING REGIONAL CO-OPERATION............................................................... 6STABILISATION OF THE WESTERN BALKANS AND EURO-ATLANTIC INTEGRATION:LESSONS FROM 15 YEARS OF INTERNATIONAL INTERVENTION .................................. 7A.OPERATIONAL ACHIEVEMENTS: THE SPECIFICITY OF INTERNATIONALINTERVENTION IN THE BALKANS ............................................................................. 71.Conflict prevention and resolution........................................................................ 72.Post-conflict: experience of international civil administration in the Balkans......... 83.NATO and EU operations in the Balkans ............................................................. 9B.POLITICAL ACHIEVEMENTS: GRADUAL INTEGRATION OF THE BALKANS INTOEURO-ATLANTIC INSTITUTIONS ............................................................................. 11HOW TO ENSURE THAT THE LEGACY OF 15 YEARS OF PEACE CONSOLIDATION INTHE WESTERN BALKANS BECOMES IRREVERSIBLE .................................................... 13A.GUARANTEEING THAT INSTITUTIONS ARE TRULY MULTIETHNIC...................... 13B.TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE RECONCILIATION ......................................................... 15C.STATE FRAGILITY: THE CASE OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA.......................... 16D.KOSOVO .................................................................................................................... 18

III.

IV.

APPENDIX 1: PRINCIPAL NATO AND EU OPERATIONS IN THE BALKANS FROM 1995 TO THEPRESENT............................................................................................................................ 24APPENDIX 2: PROGRESS IN THE PROCESS OF INTEGRATION OF BALKAN COUNTRIESINTO NATO ....................................................................................................................... 276APPENDIX 3: PROGRESS IN THE PROCESS OF INTEGRATION OF BALKAN COUNTRIESINTO THE EU ...................................................................................................................... 27

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

1

I.

INTRODUCTION

1.The year 2010 will mark the 15thanniversary of the Dayton Accord, which put an end to theconflict that had its origin in the break-up of the former Yugoslavia. There have been far-reachingchanges in the Balkans in fifteen years. Nonetheless, there are still areas of fragility in some partsof the region, as well as in certain areas of political, economic and social life.2.The international community has made a substantial investment in the stabilisation of theregion. The lessons learned from this experience have led the UN, NATO and the European Union(EU) to rethink their role and how they intervene in crisis management.3.The requirement now is to complete the task that begun 15 years ago. Completenormalisation of the situation in the region will be achieved only when the international civil andmilitary presence has finally withdrawn and the region is fully and completely integrated intoEuro-Atlantic institutions. This is the ambitious vision which governments in the region and theirinternational partners must pursue together. To achieve this, the problems and challenges thatremain in the region, particularly in Serbia/Kosovo and in Bosnia and Herzegovina, must betackled.4.This report tries to assess the results of 15 years of stabilisation and reconstruction in thewestern Balkans. The first chapter deals with the transformation of the region into a zone of sharedstability and prosperity. The second chapter sets out the lessons learned in internationalintervention in the western Balkans. Lastly, the final chapter examines some of the main obstaclesto complete normalisation of the region.5.The analysis presented in this report is based principally on several previous reports by thisCommittee, as well as on the findings of the Rose-Roth seminar held in the former YugoslavRepublic of Macedonia*on 19-21 October and of the visit of a delegation of the Sub-Committee onDemocratic Governance to Serbia on 22-23 October 2010.

*

Turkey recognises the Republic of Macedonia with its constitutional name.

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

2Western Balkans Map

The map is reproduced here with the kind authorisation of theInternational Committee of the Red Cross

II.

ACHIEVEMENTS: TRANSCENDING CONFLICT TO BUILD A ZONE OF SHAREDSTABILITY AND PROSPERITY

6.The following sections examine some of the major achievements in the last 15 years whichhave enabled the western Balkan countries to transcend the bloody conflicts that rocked the regionand to build a zone of shared stability and prosperity. The issue of integration into the EU andNATO is considered in the next chapter.

A.

ESTABLISHING A ZONE OF SECURITY AND STABILITY IN THE WESTERN BALKANS:FROM BLOODY ARMED CONFLICTS TO REFORM OF THE DEFENCE AND SECURITYSECTOR

7.Without doubt, the most important achievement in the last 15 years in the western Balkanshas been the establishment of a zone of security and stability in which the prospect of armedconflict has become unacceptable. This has been accompanied by a process of reform of thedefence and security sector in the various countries, culminating in the radical transformation of

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

3

local security institutions, which are now capable of contributing to international security as part ofmultilateral peace operations.8.The break-up of the former Yugoslavia led to the bloodiest conflict in European territory since1945. It came to an end in the autumn of 1995, having taken a very heavy toll: between 100,000and 200 000 dead in Bosnia and Herzegovina alone according to estimates, and nearly 2 milliondisplaced persons. The Dayton Accord, concluded on 21 November 1995 and signed in Paris on14 December 1995, marked the end of hostilities.9.Less than four years later there was a resumption of violence, this time in Kosovo, whereBelgrade had stepped up its repression of the actions taken by the Albanian population towardsindependence. The rejection by the Serbian authorities of the Rambouillet Accord - the peace planproposed by the international community – led to the launch of an intensive bombing campaign byNATO, which continued for 78 days between March and June 1999. The UN Refugee Agency(UNHCR) estimates that 860,000 Albanians from Kosovo fled or were deported to neighbouringStates during the period 1998-99 and that many soon returned at the end of 1999. This movementof population was followed by a second mass exodus of some 230,000 Serbs and Roma, who leftKosovo in fear of reprisals.110. The period that followed the armed conflicts in the Balkans was not free from tensions, butevents which might have affected the stability of the region – interethnic tensions in the formerYugoslav Republic of Macedonia, the independence of Montenegro, the failure of negotiations onthe final status of Kosovo and its unilateral declaration of independence – were all managedpeacefully. The profound effect of the recent violence on the collective consciousness of peoples inthe region, the punishment of the principal offenders, the strong commitment and presence of theinternational community in the region, the reform processes initiated, in particular in the securitysector, and the re-establishment of close ties – in particular economic ties – between neighbouringcountries are all factors that helped to make the prospect of a new armed conflict in the Balkansunacceptable to an overwhelming majority of the population and of the political class.11. Reform of the defence and security sector, and consequently the reform of the institutionswhich had been directly involved in the armed conflicts, was a crucial stage in consolidating peacein all the countries in the region. NATO and the EU, recognising that the Balkans’ future lies in theirfull and complete integration into Euro-Atlantic structures, made this reform a key element in theirrelations with countries in the region and so have played an essential part in steering andsupporting the reform process. We will concentrate here on defence reform. However, it should bestressed that restructuring the police in the post-conflict phase has been a fundamental element inthe consolidation of democratic institutions respecting the rule of law. The establishment of amultiethnic police force was also a key factor contributing to reconciliation among communities.Nevertheless this process was not without incident and is still incomplete, particularly inBosnia and Herzegovina.12. Although the criteria and procedures in defence reform were relatively similar in the variouscountries, the challenges which they faced differed greatly. Thus, in Bosnia and Herzegovina therequirement was to unify two completely separate armies, each with its own chain of command, atotal of 400 000 men, with strong ethnic and political allegiances and almost no democratic control.Montenegro was another special case, where the army was one of the rare prerogatives of theState Union of Serbia and Montenegro, which operated jointly up to independence. Since Serbiainherited by far the greater part of the military resources, both in men and materiel, after theseparation of the Union, Montenegro was faced with the challenge of constructing its nationaldefence rather than reforming it.

1

Some 205,000 persons are still displaced, despite efforts by the UNHCR and its local partners tofacilitate their return.

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

4

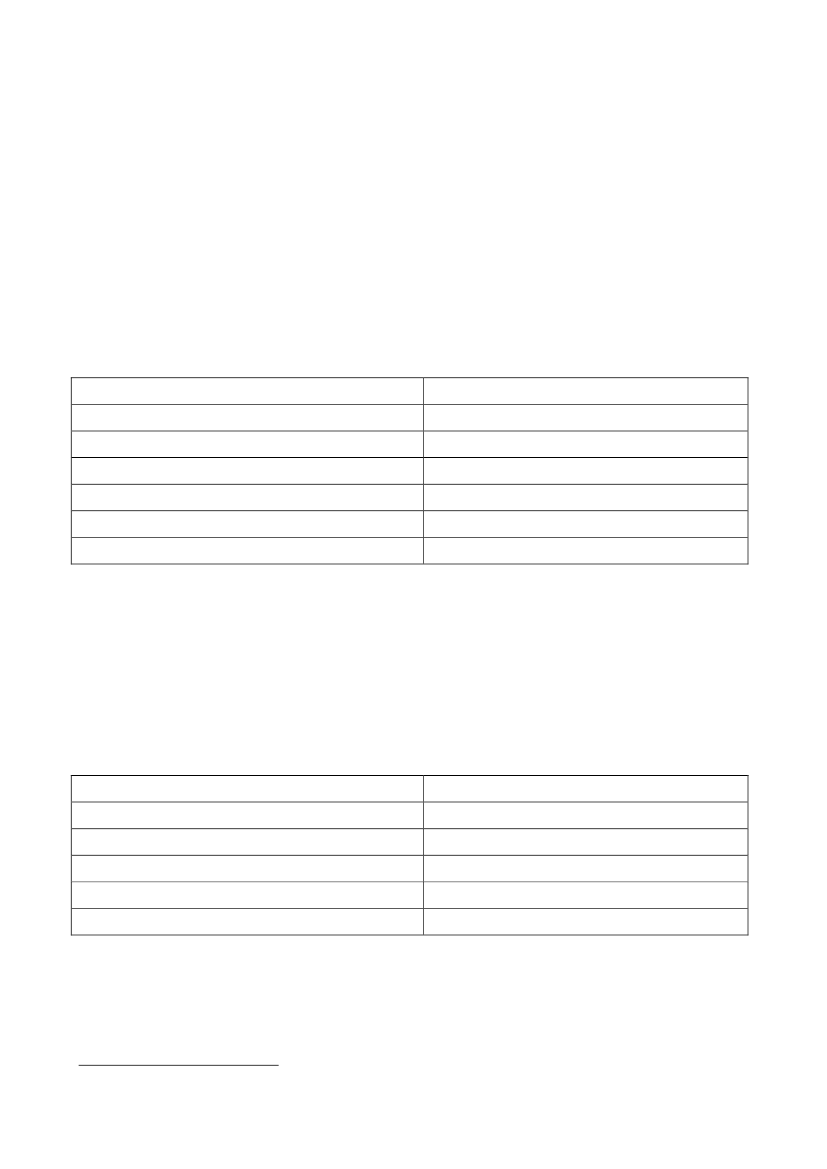

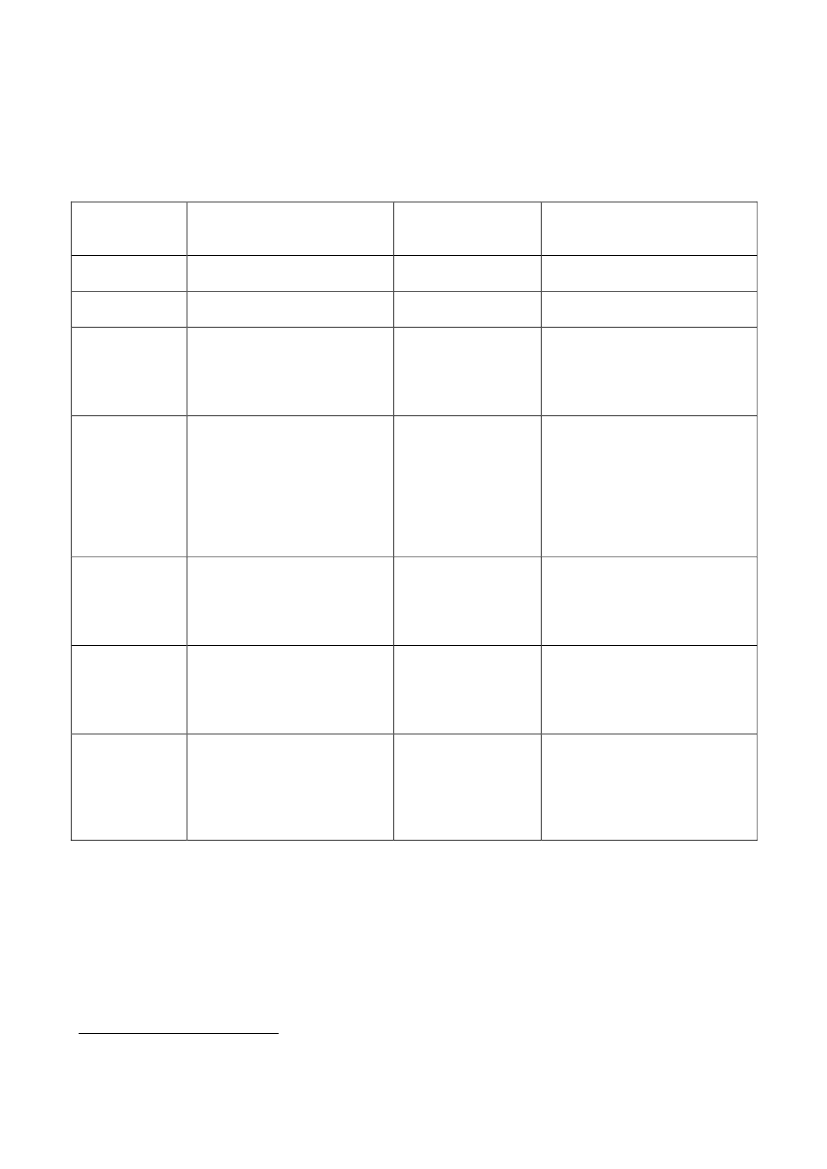

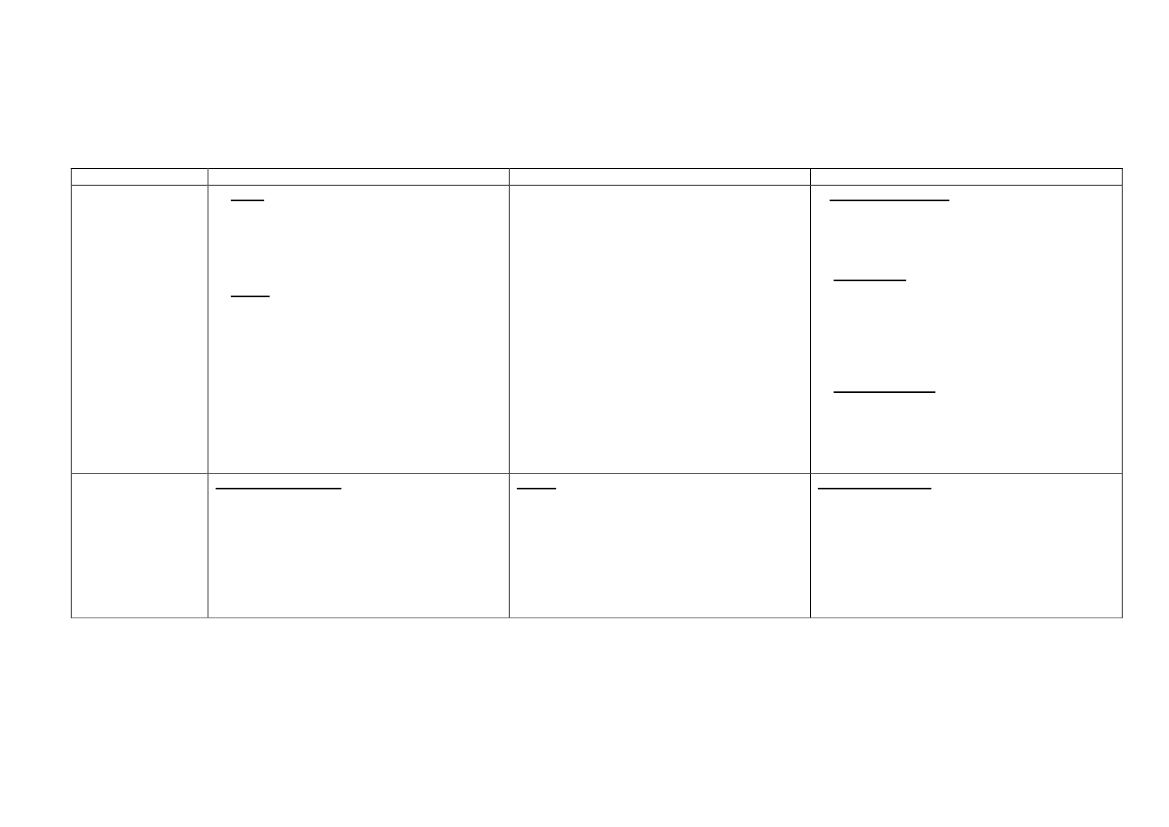

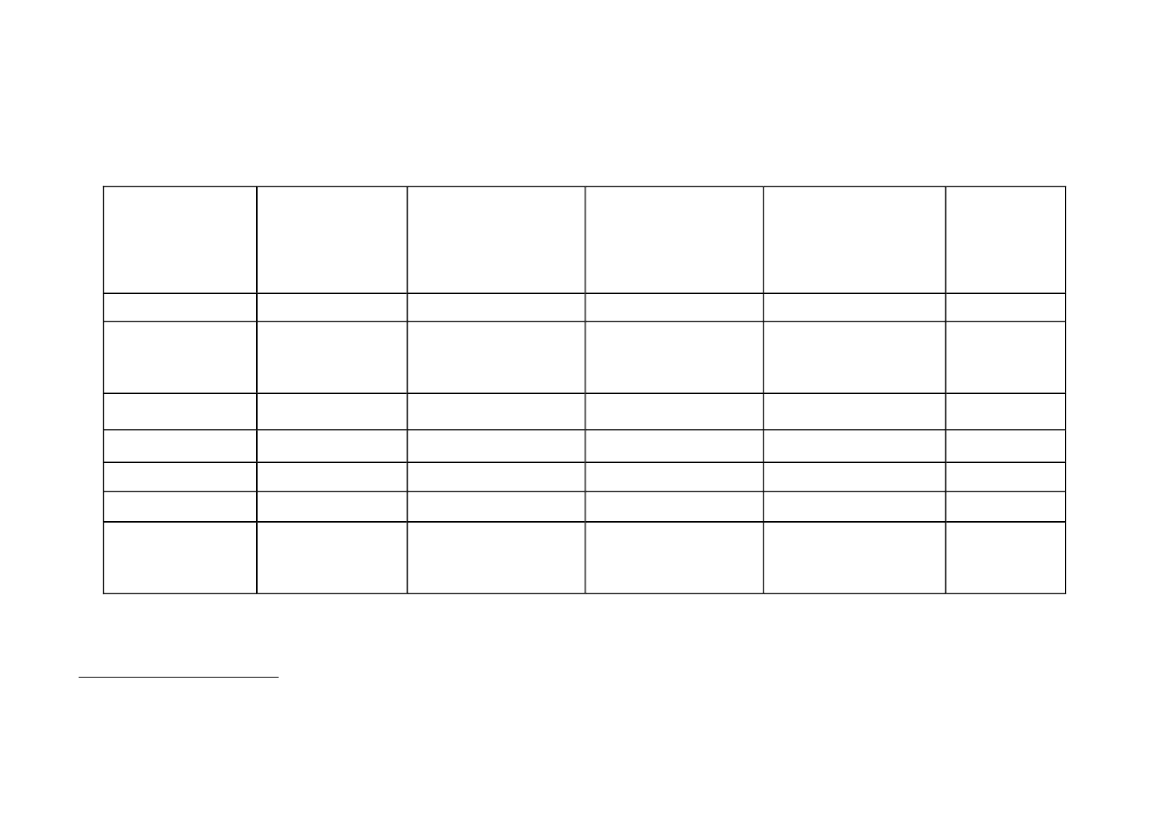

13. It was necessary to redefine defence policy principles and priorities everywhere by adoptingstrategic documents taking account of the new security environment. All countries in the regionhave decided to abolish conscription in favour of a professional army, reduced in size andmodernised2, a transformation that has been completed in some countries in the region but that isstill ongoing in others. Moreover, the key element has been to promote the interoperability of thesenew armies with NATO and to prepare them for deployments in multilateral operations. Thesefundamental changes have confronted governments in the region with a whole series of difficultchallenges: retraining of personnel, funding military retirements, modernisation of training, etc.Other important measures have also been adopted: strengthening of democratic control, and inparticular parliamentary control, revision of defence budgets, modernisation of equipment, anddestruction of obsolete and surplus weapons.Table 1: Western Balkan Countries’ Armed Forces (active)AlbaniaCroatiaSloveniaBosnia and HerzegovinaThe Former Yugoslav Republic of MacedoniaMontenegroSerbia16,50025,0009,00010,0008,0002,50028,000

Source:International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance2010 and NATO14. Today, defence reform may be regarded as a real success, as shown by Albania andCroatia’s recent accession to NATO. In particular the armies of the Balkans have demonstratedtheir willingness and their capability to be not just consumers but also contributors of security.Thus, the fact that all the countries in the region – with the exception of Serbia – are nowcontributing to NATO operations in Afghanistan is to be welcomed.Table 2: Contribution by Western Balkan Countries to the NATO International Security andAssistance Force in Afghanistan (troop numbers as at 6 August 2010)AlbaniaBosnia and HerzegovinaCroatiaMontenegroSloveniaThe Former Yugoslav Republic of MacedoniaSource: NATO295102953070240

2

Thus there has been a transition from an army of 400,000 to 10,000 men and 5,000 reservists inBosnia and Herzegovina, and from 120,000 to 16,500 men in Albania.

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

5

B.

CONSOLIDATING INDEPENDENT STATES’ IDENTITY AND STRUCTURES

15. The consolidation of independent States in the region may be regarded as anotherfundamental achievement in the last 15 years. The break-up of the former Yugoslavia has led, inseveral phases, to the creation of six new States: Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, theformer Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro3. The special case of Kosovo willbe dealt with below.16. In the early years of independence, all the States emerging from the former Yugoslavia facedthe challenge of defining their new independent State identity and establishing all the attributes oftheir statehood. The adoption of a new Constitution, the organisation of elections and theinstallation of new institutions at the central level were some of the essential stages in this process.17. Although all the States in the region reached a threshold of “State maturity” in a relativelyshort time – with the exception of Bosnia and Herzegovina, as will be seen below - this processwas still not trouble-free. In particular the definition of national and State identity raised manydifficult issues. The new States, born from interethnic conflicts, had to find a satisfactory balancebetween affirming the identity of the majority group and recognising the contribution of minoritycommunities to the national identity. This involved difficult choices as to the official language orlanguages, the place of the various communities within State structures, State symbols, etc.

C.

PUNISHING THE GUILTY

18. Punishing those guilty of crimes committed during the Yugoslav conflicts was anotheressential stage in consolidating peace in the region. To a large extent, this process was initiatedand boosted from outside, with the creation in May 1993 of the International Criminal Tribunal forthe former Yugoslavia (ICTY) by resolution of the United Nations Security Council4. However, thiswork has also been gradually taken up at local level by new national courts with specificresponsibility for trying war criminals.19. In March 2005, the date of publication of the last indictments, the ICTY had indicted161 persons, most of them for crimes committed during the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. InJune 2010, 89 cases had been decided, involving 125 persons5. Two of those accused are still atlarge, one of whom is Ratko Mladic, the military leader of the Bosnian Serbs and a major figure inthe conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. According to the targets which it set for itself in mid-2010,the Tribunal should have completed all the cases at first instance at the end of 2012 and all appealproceedings at the end of 20136.20. The ICTY experiment has been a major innovation. The Tribunal has created a precedent ininternational criminal justice and has acted as a role model for the creation of the InternationalCriminal Court. It has indicted a head of State while in office for the first time. It has contributed to3

4

5

6

Although Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedoniawere all regarded as new States, joining the United Nations between 1992 and 1993, the views as towhether Serbia-and-Montenegro was the successor State or was also a new State were far fromunanimous. The status of Serbia-and-Montenegro remained uncertain until the fall of the Milosevicregime in 2000 and until the new government’s decision to apply for membership of the UnitedNations. Montenegro became a member of the United Nations in 2006 after gaining its independence.The mandate of the ICTY is to try persons indicted for certain violations of international humanitarianlaw (serious violations of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and violations of the laws and customs of war,crimes against humanity or genocide) committed on the territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991.Its jurisdiction has also been extended to crimes committed during the Kosovo conflict.Among these 12 were acquitted, 64 were sentenced and 26 were referred to national courts for trial; inaddition, proceedings against 36 persons were abandoned, either because the charge was dropped orbecause the accused had died.Nevertheless longer time-limits have been set for the proceedings against Radovan Karadzic, theleader of the Bosnian Serbs, brought before the Tribunal in July 2008.

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

6

the development of international humanitarian law and has defined its key concepts. It has made itpossible to throw light on some of the darkest episodes in Europe’s recent history and has giventhe victims a voice. Lastly, it has contributed directly and indirectly to strengthening the rule of lawand the legal system in countries in the Balkans.21. However, punishing the guilty has not been a purely international matter; States in the regionhave also played a more and more active part in it. First of all, after an initial phase of distrust, oreven defiance, co-operation by governments in the region with the Tribunal has steadily improved,even though some problems remain. Moreover, States in the region have gradually been setting upcourts with specific responsibility for war crimes trials. These local courts have an essential role,especially having regard to the impending closure of the ICTY.

D.

DEVELOPING REGIONAL CO-OPERATION

22. The steady integration of the Balkan countries into Euro-Atlantic institutions has gone hand inhand with the development of a dense network of regional co-operation structures. This processhas sometimes suffered from a lack of interest on the part of governments in the region, and fromblockages linked to various political tensions and problems. Some people have also observed,quite rightly, that the proliferation of structures does not necessarily guarantee actualachievements, neither is it an indicator of the quality of co-operation. The fact remains, however,that the installation of all these frameworks for regional co-operation has indisputably contributed tothe success of the peace consolidation process in the Balkans, by increasing the number ofpolitical, economic, social and security links between countries in the region. Although the initialimpetus came from the international community, priority has gradually been given to localownership, a development which should be welcomed.23. Until recently, the Stability Pact for South-Eastern Europe (SPSEE), adopted in June 1999 by39 countries and 17 international organisations, was the principal tool used by the internationalcommunity to promote regional co-operation in the Balkans. The Pact provided a framework withinwhich several regional initiatives in trade, energy, combating organised crime, populationmovements, etc. could be developed. Moreover, the European Union’s Association andStabilisation Process and NATO’s South-East Europe Initiative have played an important part inpromoting regional co-operation as a complementary dimension of the European and Euro-Atlanticintegration process.24. Among the purely regional initiatives, the South-East European Cooperation Process(SEECP) deserves a special mention. Set up in 1996, it still provides today the main forum forregional political dialogue. It was under the aegis of the SEECP that the Regional CooperationCouncil (RCC), which took over from the Stability Pact in February 2008, was created. Unlike thePact, the RCC is controlled by the countries in the region, and therefore likes to regard itself as thesymbol of local ownership. Council activities are concentrated on six priority areas: economic andsocial development, energy and infrastructures, justice and internal affairs, security co-operation,the development of human capital and parliamentary co-operation.25. Several noteworthy initiatives have been taken in the field of security. In particular theSouth-Eastern Europe Defence Ministerial (SEDM), launched in 1996, has made it possible tostrengthen military co-operation and interoperability, supplementing the efforts made in NATO. Theflagship initiative in this area is the South-Eastern Europe Brigade (SEEBRIG), a multinationalforce available for peacekeeping missions. Special reference should also be made to theco-operation between Albania, Croatia and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, with theaddition of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro in September 2008, within the framework ofthe Adriatic Charter, an initiative developed in partnership with the United States with the aim ofstrengthening co-operation among participating States with a view to joining NATO.26. The successful implementation, under the auspices of the OSCE, of the 1996 FlorenceAgreement on Sub-regional arms control, adopted in accordance with Article IV Annex 1-B of theDayton Accord, has also made a decisive contribution to achieving balanced and stable defence

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

7

force levels within the geographical area of the Agreement (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia,Montenegro and Serbia). This document provides a framework for establishing numerical limits ofheavy weapons and voluntary limitations on military personnel, as well as implementing anintrusive arms control inspection regime.

III.

STABILISATIONINTEGRATION:INTERVENTION

OF THE WESTERN BALKANSLESSONS FROM 15 YEARSTHESPECIFICITY

ANDOFOF

EURO-ATLANTICINTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL

A.

OPERATIONALACHIEVEMENTS:INTERVENTION IN THE BALKANS

27. Experience gained in intervention in the Balkans has made a substantial and directcontribution to the evolution of methods of crisis and conflict management in the post-Cold Warworld. Thus, the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia have led the UN to rethink its peacekeepingoperations. They have also contributed to changes in NATO’s role and to the steady emancipationof the EU in the area of defence and security policy.28. Although the international community has been involved in all the conflict and post-conflictphases in the former Yugoslavia, its achievements have been mixed, to say the least. In particularthe interventions in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo have highlighted the weakness of conflictprevention machinery and the many difficulties, both political and operational, that may erode theeffectiveness of a multinational military intervention. The post-conflict phase has seen a substantialdeployment of resources and the establishment of legal and institutional mechanisms with manyexceptional features, which made some notable achievements possible. The fact remains,however, that after over 15 years of international presence in the Balkans it has not yet beenpossible to meet all the requirements for complete normalisation.1.Conflict prevention and resolution

29. Conflict prevention and resolution is undoubtedly the area in which international action hasbeen least successful.30. The escalation of the conflict in Kosovo in particular has shown the international community’sinability to foresee and prevent the crisis, in spite of intense diplomatic activity in the monthspreceding military intervention. Consequently the political deadlock in the UN Security Councilcompelled NATO to take the initiative in military intervention alone, in order to end the violence.The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia is the only example of real success in preventingconflicts in the region. Here reference should be made to the support given to the authorities in thecountry at the time of the Kosovo conflict to manage the influx of refugees and to avoid indirectdestabilisation. The active contribution by NATO and the EU to the conclusion and implementationof the Ohrid Framework Agreement should also be emphasised: this agreement helped dampdown the interethnic violence which had broken out in the country early in 2001.31. The conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina has revealed the many weaknesses in thepeacekeeping operation set up by the United Nations: an unsuitable mandate, giving preference tointerposition and neutrality to the detriment of imposing peace; reluctance of member-States toprovide the necessary troops on the ground; late and limited use of the threat to use force; andineffective sanctions, which altered the balance of forces on the ground. The internationalcommunity finally managed to put an end to hostilities only by making the transition to a peaceimposition phase, in particular through NATO air strikes.32. Experience in the Balkans has prompted a far-reaching reappraisal of UN peacekeepingoperations. The 2000 report by the group of experts led by the Algerian diplomat Lakhdar Brahimi

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

8

seeks to learn from the failure of UN interventions in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Rwanda. Itstresses the necessity for UN peace operations to have a clear, credible and realistic mandate,supported by a strong and sustainable political consensus among Security Council members andimplemented by troops in sufficient numbers and with robust rules of engagement. Today,however, UN peace missions still meet these requirements but rarely.2.Post-conflict: experience of international civil administration in the Balkans

33. The post-conflict phase has seen a remarkable deployment of resources. This timeinternational action was able to rely on a broad political consensus and robust mandates. Thecreation of the ICTY is one of the noteworthy factors in international intervention. Here, however,we will concentrate on another essential and remarkable aspect of international experience in theBalkans, namely the establishment under the aegis of the United Nations of internationaladministrative and supervisory mechanisms in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Kosovo7. In bothcases a representative of the international community with binding powers was given the task ofsupervising the implementation of the peace agreements8.34. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, these duties are performed by the High Representative.Pursuant to the Dayton Accord, the High Representative has ultimate authority in respect ofinterpretation and implementation of the civil aspects of the Accord. He is totally independent of thelocal authorities and is answerable only to the Peace Implementation Council (PIC), the principalco-ordinating authority for implementing the civil aspects of the Dayton Accord. The “Bonn powers”granted to the High Representative in 1997 enable him to quash decisions taken by the localauthorities, to impose certain decisions and to dismiss local officials.35. In Kosovo, interim civil administrative duties are performed by the United Nations InterimAdministration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), under the leadership of the United Nations SecretaryGeneral’s Special Representative, who acts as the ultimate authority in Kosovo. The internationalcivil presence in Kosovo has been reconfigured since the declaration of independence in February2008 in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 1244, which continues to provide thelegal framework essential to international action in Kosovo. This reconfiguration has ledinter aliatoa substantial reduction in the role of UNMIK. At the same time, the institution of InternationalCivilian Representative (ICR) was established which, pursuant to the Kosovar Constitution, isresponsible for supervising implementation of the principles of the Ahtisaari Plan9by the Kosovarauthorities, and has ultimate authority regarding interpretation of the civil aspects of the plan.7

89

It should be noted, however, that the exercise by the UN of territorial civil administrative functions didnot begin in the Balkans and is not characteristic of this region. In particular, the United Nations interimadministration missions in Cambodia in 1992-1993 and in East Timor in 1999-2002 may be cited asexamples.It is important to stress that in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as in Kosovo, the local authorities expresslyconsented to the installation of such international administrative mechanisms.In November 2005 the United Nations Secretary General had given Martti Ahtisaari, the formerPresident of Finland, the task of devising a plan to solve the problem of defining the final status ofKosovo. After months of fruitless negotiation Mr. Ahtisaari had submitted his plan, consisting of aReport and a Comprehensive Proposal, to the Secretary General. Although there was no expressreference to independence this plan, passed to the Security Council on 26 March 2007, provided thebasis for the creation of an independent State of Kosovo, with a Constitution, its own symbols of Stateand security forces, as well as the right to membership of international organisations. It alsoreorganised the international civil presence in Kosovo. The Ahtisaari Plan had been welcomed by theKosovo Albanians, NATO, the European Union and their member States individually. In contrast,Kosovo Serbs, supported by Belgrade and Moscow, strongly opposed it. As a result, it had not beenpossible to find any agreement within the Security Council to ratify the plan. In their declaration ofindependence the Kosovar authorities nevertheless undertook to implement the Ahtisaari Plan, andthe Kosovar Constitution is strictly in accordance with the criteria set in the Comprehensive Proposal.On the history of the negotiations on the final status of Kosovo and the Ahtisaari Plan see the twoReports submitted to this Committee by Vitalino Canas: “Kosovo and the Future of Balkan Security”[163 CDS 07 E rev. 2] and [155 CDS 08 E].

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

9

However, the office of ICR is not endorsed by the UN, and his authority is acknowledged only byPristina and by States which have recognised the independence of Kosovo. UNMIK and the ICRthus continue to operate in parallel, a coexistence which is unfortunately detrimental to theconsistency of international action in Kosovo.36. Although the UN has provided the essential framework for the international civil presence inBosnia and Herzegovina, as in Kosovo, certain tasks have also been passed on to otherorganisations, in particular the OSCE and the EU. The good co-operation among these variousorganisations is generally regarded as one of the factors to the credit of international action in theregion.37. In 15 years of intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina and over 10 years in Kosovo, theinternational civil presence has had a key role in securing political stability and laying thefoundations for interethnic reconciliation. It has also initiated and directed the process of creatingand consolidating institutions and, more widely, political, economic and social reforms.38. However, international action has also encountered several major problems. By making theinternational presence primarily responsible for reforms, the international administrativemechanisms have indirectly contributed to undermining the local authorities’ sense of responsibilityand encouraging apathy in a population which has difficulty in identifying with decisions seen asimposed from outside. In such a context it is easy, and a good move politically, to impute errorsand failures to the international community. Thus, Bosnia and Herzegovina has gone throughseveral phases in which the international presence, and in particular the binding powers of theHigh Representative, have been challenged, a challenge which is re-emerging today, particularly inthe Republika Srpska (RS). UNMIK also has regularly been the target of criticism by localauthorities, criticism which has grown stronger after the declaration of independence. Moreover,while the authority of the ICR is recognised and accepted by Pristina, Belgrade on the contraryregards this office as illegal.39. These challenges to the international presence have also highlighted the limits on the use ofbinding powers by the international community and the importance of having positive incentivesavailable which can supplement and reinforce the negative incentives linked to the power ofsanction. In this sense, the prospect of European and Euro-Atlantic integration and implementationof the conditionality principle have played an essential part in support of the measures taken by theHigh Representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina and by UNMIK in Kosovo.40. However, it is important for international bodies to be accountable for their actions anddecisions in order for the international community to be seen as legitimate. This presupposes theestablishment of clear audit and accountability mechanisms, a dimension that should receive moreattention in future.41. It is yet too early to pass definitive judgement on the international action in the post-conflictphase in the former Yugoslavia. The international community’s ability to “orchestrate its departure”,i.e. to arrive at a situation in which the abolition of the international supervisory mechanismsculminates in the transfer of authority to local stable, democratic, multiethnic and economicallyviable institutions, is what will govern the success or failure of international intervention in the finalanalysis.3.NATO and EU operations in the Balkans

42. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, as in Kosovo, the task of ensuring security in the post-conflictphase was initially given to NATO by the UN Security Council. The Alliance also made an activecontribution to stabilising the situation in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. However, theEU has gradually taken over in these three theatres as it developed its capability to mount civil and

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

10

military operations as part of the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP)10. The Table inAnnex 1 shows the principal NATO and EU operations in the region since 1995.43. As discussed in the previous chapter, the re-establishment of a stable and safe environmentis one of the indisputable successes of international intervention in the Balkans. In addition to theirimpact on the ground, NATO and EU operations have also contributed to far-reaching changes inboth organisations and helped to make them indispensable players in the region.44. It should be borne in mind that NATO’s intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina was theAlliance’s very first use of armed force, as part of operationDeny Flightprotecting air exclusionzones. This is also NATO’s first out-of-area intervention. More generally, with the deployment ofIFOR (Implementation Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina) and then SFOR (Stabilisation Force),NATO went beyond its central mission of collective defence and was involved in crisismanagement for the first time. The operations conducted by the Alliance in Bosnia andHerzegovina and in Kosovo have profoundly influenced discussions on the future of NATO in thepost-Cold War world. They have highlighted the fact that the security of the European continent isdirectly dependent on the stability of its immediate neighbourhood. They have also helped to definenew roles for the Alliance,inter aliain the area of crisis stabilisation and management. The 1999Strategic Concept, which is the outcome of these discussions, reflects the various lessons learnedfrom NATO’s experience in the Balkans.45. In the same way the Balkans have transformed the EU by leading to the development of civiland military crisis management capabilities as part of the ESDP. The EUPM (EU police Mission) inBosnia and Herzegovina is the very first ESDP mission and the EUFOR-Concordia operation(European Union Force operation) in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia the very firstmilitary operation. In December 2008, the EU also deployed its largest ESDP mission in Kosovo,EULEX (European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo).46. Increasing participation by partner countries in operations has been another noteworthyaspect of NATO and EU interventions in the Balkans, a trend which has since become even morewidespread and significant. Participation by Russian troops in SFOR and KFOR (Kosovo Force)has been a noteworthy precedent in this respect11.47. NATO and EU operations in the Balkans have also been an opportunity to lay the foundationfor institutional co-operation between these organisations, which was formalised in the March 2003Berlin Plus agreement. This agreement provides a framework allowing the EU to use the planningcapabilities and other resources of NATO to conduct its own operations. Thus, Berlin Plus hasbeen used successfully for EUFOR-Concordia operations in the former Yugoslav Republic ofMacedonia and for EUFOR-Althea in Bosnia and Herzegovina and has facilitated a handoverbetween NATO and EU operations in the two countries. Moreover, in July 2003 the EU and NATOjointly published a “concerted approach for the Western Balkans”, which defines the main lines ofco-operation between the two organisations and stresses their joint commitment to stability in theregion. Joint meetings of the North Atlantic Council and the EU Political and Security Committeeare held from time to time to consider developments in the situation in Bosnia and Herzegovinaand implementation of EU-NATO co-operation within the Berlin Plus framework.48. In January 2010, the EU Council took note of “decisive progress by the ALTHEA operationtowards fulfilling its mandate, and in particular the completion of the military tasks and stabilisation10

11

The ESDP has become the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) since the entry into force ofthe Lisbon Treaty. In this Report the title ESDP will continue to be used regarding operations launchedbefore the adoption of the Lisbon Treaty.Partner countries’ contributions today account for some 20% of KFOR strength, with contributions fromAustria, Finland, Ireland, Morocco, Sweden, Switzerland and Ukraine. As for the EU, particularreference may be made to the American contribution to the EULEX mission in Kosovo, or toparticipation by Albania, Chile, Switzerland, Turkey and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia inEUFOR-Althea.

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

11

set out in the Dayton/Paris Peace Agreement” and therefore decided on an adaptation of theEUFOR mandate. While retaining certain executive tasks, from now on EUFOR will also help tostrengthen capabilities and contribute to training as part of the reform of the security sector, afunction already fulfilled to a large extent by the NATO presence in the country. During the visit bya NATO-PA delegation to Sarajevo in June 2010, the EUFOR Commander nevertheless stressedthat the EU-NATO relationship in Bosnia and Herzegovina was a model of mutually beneficialco-operation, especially in capability building and training. In his view, EUFOR has identified theminimum resources necessary for maximum effect without duplicating existing initiatives.1249. However, it should be noted that while the achievements of EU-NATO co-operation in theBalkans are on the whole positive, this remains to a large extent an isolated precedent. SinceEUFOR-Althea, the EU has no longer made use of the Berlin Plus agreement for another ESDPoperation. Moreover, NATO and EU operations are more and more frequently deployed side byside, a situation not covered by the Berlin Plus agreements. This is the case, for example, inKosovo or in Afghanistan, where a NATO military operation and an EU civilian mission coexist, orin Somalia, where both NATO and the EU have a military presence. Admittedly ad hoc methods ofco-ordination have been established on the ground, but we are far from the “strategic partnership”set out in the December 2002 EU-NATO joint statement on the EDSP. The EU should beencouraged to reciprocate NATO’s positive steps with a view to taking NATO-EU relations furtherin accordance with the agreed framework50. The principal challenge for NATO, as it is for the EU, in the future will be managing thegradual withdrawal of international forces. In Bosnia and Herzegovina the EUFOR presence hasalready been reduced substantially since 2007, from some 7,000 men to about 1900 today. In June2009, Alliance Defence Ministers acknowledged that the improvement in the security situation inKosovo was making gradual adjustments to KFOR dispositions towards a deterrent presencepossible. In practice this takes the form of a reduced presence – about 10,000 men – and greatermobility. The first phase in this process was completed in February 2010. It should be stressed thatthe transition to the next stages in the deterrent presence is not automatic, but will have to beapproved by the North Atlantic Council on the basis of an assessment of the situation on theground.13For the time being the Council has taken the view that these conditions had not yet beenmet.

B.

POLITICAL ACHIEVEMENTS: GRADUAL INTEGRATION OF THE BALKANS INTOEURO-ATLANTIC INSTITUTIONS

51. The process of gradual integration of the Balkan countries into Euro-Atlantic institutions hasindubitably been a crucial factor in promoting regional stabilisation and the reform process in thepolitical, economic, social and security fields. At the Feira European Council in June 2000, the EUendorsed the prospect of future membership of all the countries in the western Balkans. This goalwas confirmed at the Thessaloniki European Council in June 2003. NATO’s open door policy alsorecognises the eligibility of these countries to join the Alliance in accordance with Article 10 of theWashington Treaty, which states that the Alliance is open to any European State “in a position tofurther the principles of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area”.14The countries in the region have all made integration into NATO and the EU a key goal of theirforeign policy. Only Serbia still rules out any prospect of joining NATO for the time being15, but the121314

15

See the mission report [194 DSCFC 10 E].Stages 2 and 3 should lead to additional phased force reductions, 5,700 and 2,500 troopsrespectively.The Heads of State and Government of the Alliance also reaffirmed at the Strasbourg-Kehl Summit inApril 2009 that “[w]e remain committed to the Balkans, which is a strategically important region, whereEuro-Atlantic integration, based on democratic values and regional cooperation, remains necessary forlasting peace and stability”.Belgrade’s position on the issue of NATO membership was explained to the delegation of theSub-Committee visiting Belgrade on 22-23 October 2010. See the mission report [263 CDS 10 E], andin particular paragraph 9: “Parliamentarians noted that the 2007 parliamentary declaration on neutrality

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

12

country takes an active part in the Partnership for Peace, has adopted a new Security Strategywhich provides for greater participation in peacekeeping operations, and is considering concludingan Individual Partnership Action Plan (IPAP) in 2011. In 2004, Slovenia became the first country inthe region to join the EU and NATO. Albania and Croatia joining NATO in April 2009 markedanother major stage in the process of Balkan integration into Euro-Atlantic institutions.52. In their relations with the Balkan countries, NATO and the EU have been able to rely onexperience gained in the previous rounds of enlargement to central and Eastern Europe. However,both organisations have also had to develop new political and institutional tools to assist candidatecountries along the path to integration. The tables in Appendices 2 and 3 set out in detail theprincipal stages in these processes in the context of NATO and the EU and the progress made byeach of the Balkan countries.53. On the whole, it can be said that the parallel processes of integration into NATO and the EUhave been complementary and mutually reinforcing. As in central and eastern Europe, joiningNATO is widely seen by governments in the region both as a goal in itself and as an importantstage on the way to integration into the EU. Both organisations have also adopted similarapproaches, based on consideration of the merits of each candidate rather than on a regional orcountry bloc approach. Both of them have also left plenty of room for the principle of conditionality,whereby the transition to future stages in integration depends on measurable progress in thereform process and full and entire co-operation with the ICTY.54. However, the integration process has not been trouble-free. First of all, it is regrettable thatno real EU-NATO co-ordination exists at the political level, either in defining or in monitoringenlargement policies, although criteria for accession are highly complementary, especially in theareas of political reform. The implementation of conditionality has also proved to be especiallytricky. Too strict a conditionality is likely to erode the support of the local population for integrationas well as the positive effect that the integration process has in encouraging the implementation ofreforms. Too flexible or inopportune application of the condition is likely to call the credibility of theEU and NATO into question and to cast doubt on their members’ political will to defend the criteriaand norms that are the foundation of the accession process. Lastly, the discussion that hasemerged in recent years as to the EU’s absorption capacity has been seen in the region asindirectly calling the Thessaloniki promise of integration into question. The entry into force of theLisbon Treaty should now enable the Union to end the institutional debate and facilitate impendingenlargements.55. However, the full and complete integration of the Balkans into Euro-Atlantic institutions is stilla relatively distant prospect, due in particular to the specific difficulties raised by certainapplications. This is the case with, for example, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia: inspite of indisputable progress in the reform process, the country’s application to NATO, and to theEU, continues to suffer from the failure to resolve the difference with Greece over the name.Political blockage and a slowdown in the reforms in Bosnia and Herzegovina have also held up theintegration of the country and prevented the closure of the Office of the High Representative andthe transition of the international civil presence, a transition which is regarded as an essentialprecondition for accession. Lastly, Serbia and Kosovo are a particularly difficult case for the EUand NATO, having regard to the fact that certain member States of both organisations have notrecognised the independence of Kosovo. The EU has stated several times that the issue of Kosovoand that of Serbia’s integration are not linked and will continue to be treated separately. In fact theEU is continuing to encourage Serbia’s integration while at the same time maintaining its supportfor the reform process in Kosovo and recognising Kosovo’s “clear European perspective”. Althoughthe question of Serbia’s joining NATO does not arise for the time being because of the presentstrategic orientation chosen by Belgrade, in the long term the Alliance will have to manage the

was binding on the current government, and that the issue of NATO membership would have to bedecided jointly by state authorities and the population.”

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

13

aspirations of Pristina, which has already made joining NATO one of the priorities in its foreignpolicy.56. However, the extent to which the prospect of integration into NATO and the EU is still amagnet and a key factor in stability for the region should be emphasised. To continue in this role,this prospect must remain open and credible for all the countries in the region. The membercountries of these two organisations have an historic responsibility to complete the process of fulland complete integration of the Balkans into the transatlantic area of peace, stability andprosperity.

IV.

HOW TO ENSURE THAT THE LEGACY OF 15 YEARS OF PEACECONSOLIDATION IN THE WESTERN BALKANS BECOMES IRREVERSIBLE

57. In the sections that follow we will tackle only some of the most serious problems which,failing a suitable solution, would be likely to erode the remarkable progress made in the region inthe last 15 years. However, reference might also be made to other challenges that call for closerattention: completion of the reform of the security sector, in particular with regard to police reformand democratic control; continuing political reforms, including consolidation of the politicallandscape and combating corruption; combating organised crime.

A.

GUARANTEEING THAT INSTITUTIONS ARE TRULY MULTIETHNIC

58. Building societies and institutions that are truly multiethnic is an essential condition for peaceconsolidation in the region, but is still a substantial challenge in several countries. Interethnicrelations pose specific challenges in Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as in Serbia, in connectionwith the situation in Kosovo. These special cases will be considered below. In other countries inthe region problems persist, varying in extent, in several areas:-implementation of the constitutional and legislative framework for the political representationand participation of minorities in institutions of central government;-implementation of decentralisation and local government measures;-minority representation in the principal public services: the armed forces, the police, the legalsystem, etc.;-non-discrimination and respect for minority rights (culture, language, education, access toemployment, etc.);-resolution of problems connected with refugees and displaced persons.

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

14

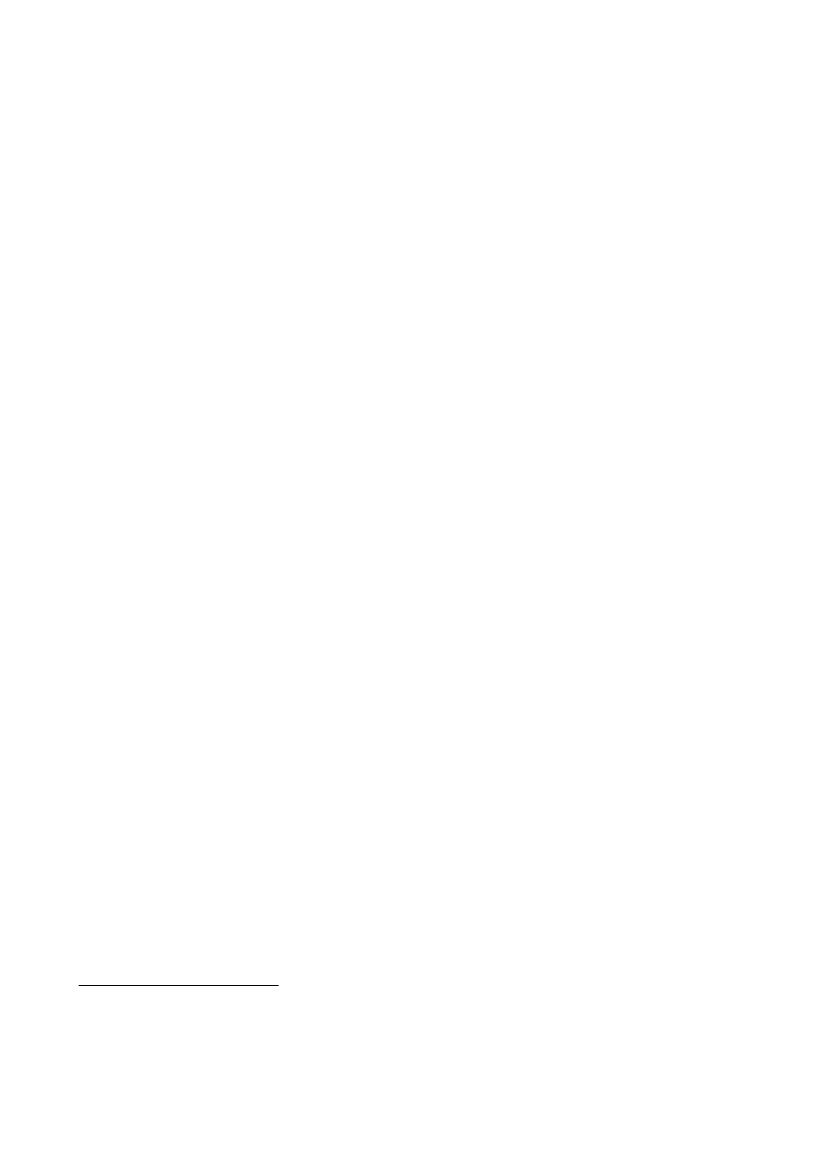

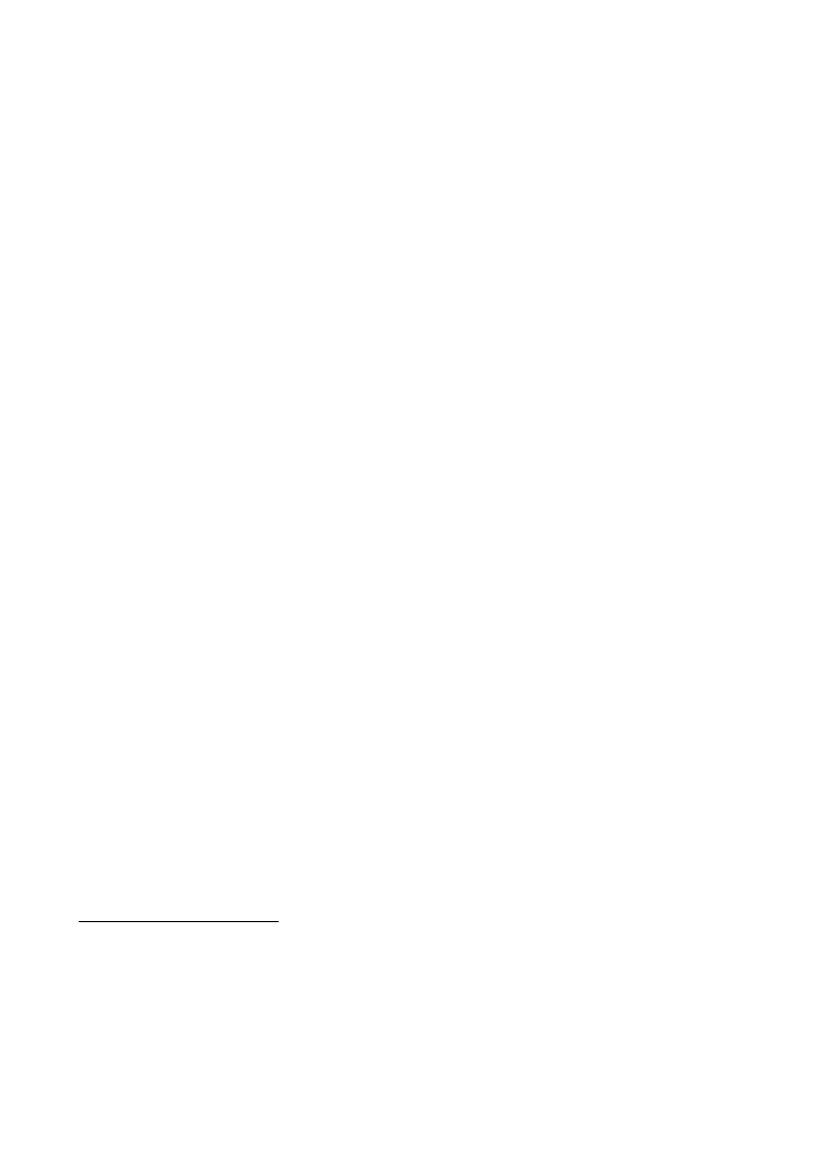

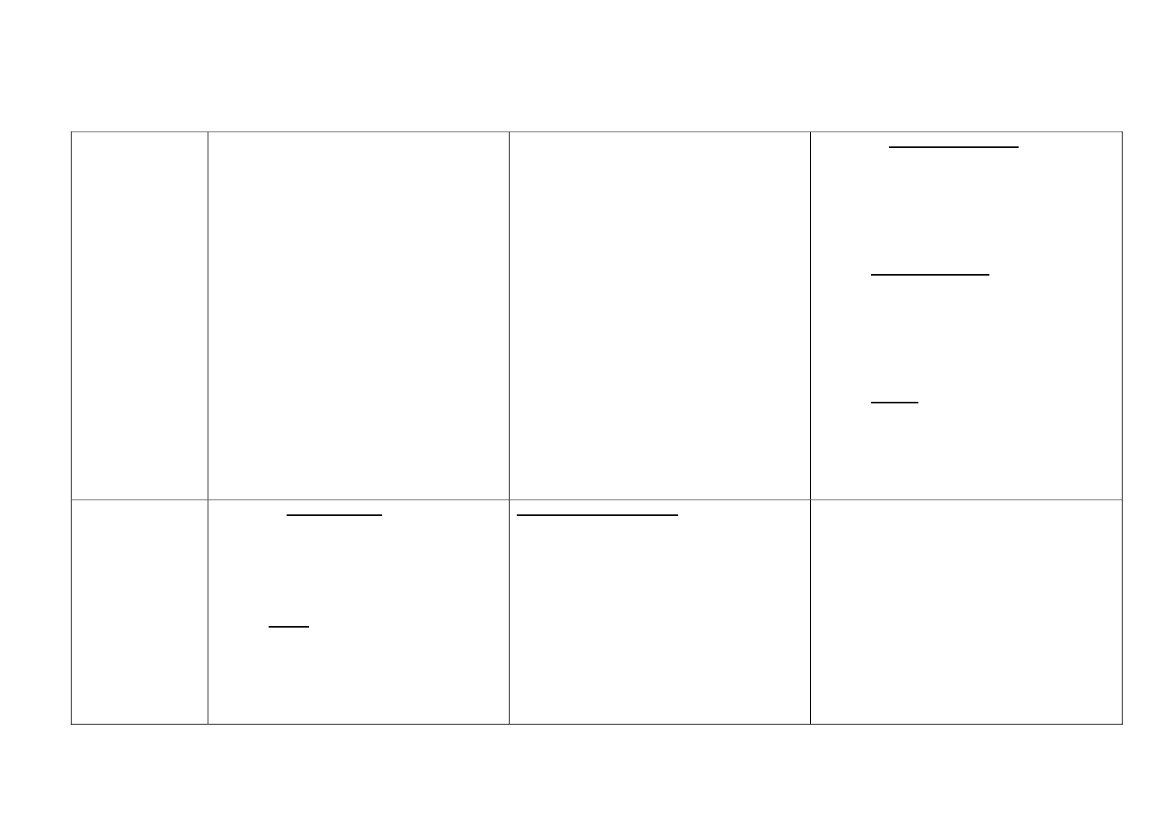

Table 3: Official language(s) of Western Balkan Countries and Demographic Data16(Note:the designation used for the languages and ethnic groups are as per local authorities; thisdoes not necessarily represent the official view of the Assembly)Official language(s)AlbanianPopulationEthnic composition(Source:NationalStatistics Offices)3.2 million95% Albanians (source:Foreign Ministry)and 3.8 millionNo census since 19914.4 million89.6% Croats, 4.5% Serbs,others (2001census)

AlbaniaBosnia andHerzegovinaCroatia

the formerYugoslavRepublic ofMacedonia

Montenegro

Serbia

Slovenia

Bosniac,CroatianSerbianCroatianMinority languages are alsoused officially under theconditions prescribed by thelaw.MacedonianIn municipalities where over20% of the populationbelongs to an ethnic groupother than Macedonian, thelanguage of that group alsohas the status of an officiallanguage.MontenegrinSerbian, Bosniac, Albanianand Croatian are alsorecognisedasofficiallanguages.SerbianMinority languages are alsoused officially under theconditions prescribed bylaw.SlovenianItalian and Hungarian arealso recognised as officiallanguages in municipalitieswhere Italian and Hungariancommunities reside.

2 million

64% Macedonians, 25%Albanians, others (Turks,Roma, Vlachs, Serbs,Bosniacs)(2002census)

0.62 million

43% Montenegrins, 32%Serbs, 7.7% Bosniacs, 5%Albanians, others(2003census)82.8% Serbs, 3.9%Hungarians, 1.8% Bosniacs,others(2002census; excludingKosovo)83% Slovenes, 2% Serbs,1.8% Croats, 1.1% Bosniacs,others(2002census)

7.3 million

2 million

59. The case of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia deserves special mention. Despiteconsiderable and indisputable achievements, implementation of the Ohrid Accords, concluded inAugust 2001 and seeking to put an end to interethnic violence, still gives rise to problems. It alsoremains a reason for tension with political parties representing the Albanian minority; the DUI(Democratic Union for Integration) in 2007, then since August 2009 the DPA (Democratic Party ofAlbanians), have taken it in turns to boycott parliament to denounce the failure to implement certainprovisions in the Ohrid Agreement. The October 2009 Progress Report by the EuropeanCommission lays stress on progress in implementing laws on languages, on decentralisation andon equitable representation, but notes that “further efforts in a constructive spirit are needed to fulfil16

The demographic data for Kosovo are extremely unreliable, in view of the fact that there has been nocensus since 1991. According to estimates by the Kosovo Statistics Office for 2010, the Kosovarpopulation is 2.18 million, 92 % of whom are Albanian. The Kosovar authorities are hoping to organisea census in April 2011. The Kosovar Constitution recognises two official languages, Albanian andSerbian: Turkish, Bosnian and Romani are also used officially under the conditions prescribed by law.

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

15

the objectives of the Agreement” and that “continued efforts to deepen political dialogue includingon interethnic issues would consolidate the engagement of all parties”. The Membership ActionPlan for the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia for 2009-2010 refers to the same areas ofprogress and the same weaknesses.

B.

TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE RECONCILIATION

60. As described in Chapter II, the ICTY and the local courts responsible for war crimes trialshave played a remarkable part in ensuring that serious crimes committed during conflicts in theformer Yugoslavia do not go unpunished. However, this process still has to be brought to an end.Several important questions remain in this respect:-two individuals with a key role in the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia are still on the run;their arrest must remain an absolute priority and calls for increased efforts by governments inthe region, in co-operation with the ICTY; the question also arises whether the ICTY will bemaintained in its present form or with a streamlined structure to allow the two accused to betried, or whether an alternative solution can be found;an appropriate solution should also be found to the problem of preserving the legacy of theICTY and in particular the storage of its archives;the resources of the local courts responsible for war crimes trials must be increased stillfurther;improving co-operation by governments in the region with the ICTY and regionalco-operation in police and legal matters should also continue.

---

61. Alongside the completion of individual proceedings, reconciliation also comes through thesettlement of the genocide cases pending before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) involvingCroatia and Serbia. Unfortunately, negotiations between the two governments for the withdrawal ofthe Croatian Application filed in July 1999 have still not been successful and Serbia filed aCounter-Application in January 2010.62. The case filed by Bosnia and Herzegovina against Serbia in March 1993 ended in February2007 with recognition by the Court that Serbia has no committed genocide, but was responsible forfailing in its obligation to prevent the commission of genocide17. The positive reaction of theSerbian authorities to the judgment, and in particular the adoption by the Serbian Parliament on 30March 2010 of a resolution condemning the atrocities in Srebrenica, should be welcomed. Thisresolution, and the discussions preceding its adoption, mark a fundamental stage in the publicdebate on crimes committed during the Yugoslav conflicts, an important and necessary debate inall the countries in the region.63.The question of the Advisory Opinion of the ICJ on Kosovo is touched upon below.

64. The settlement of the missing persons issue is another essential stage in the reconciliationprocess. According to the July 2010 estimates by the International Committee of the Red Cross(ICRC), there are still 10,419 unsolved cases connected with the conflict in Bosnia andHerzegovina and 1,839 connected with the conflict in Kosovo. It is essential that governments inthe region continue to keep this issue under close scrutiny and, with the support of the ICRC, bringthe efforts to settle all the still unsolved cases to a successful conclusion.65. In general, it is the implementation of a whole range of long-term internal and externalmeasures that will secure firmly established and sustainable reconciliation in the region. Internally,17

However, the Court rejected the application for financial compensation, taking the view that “[s]ince theCourt cannot therefore regard as proven a causal nexus between the Respondent’s violation of itsobligation of prevention and the damage resulting from the genocide at Srebrenica, financialcompensation is not the appropriate form of reparation for the breach of the obligation to preventgenocide”.

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

16

special priority must be given to education and to strengthening truly multiethnic societies.Externally, the enhancement of regional co-operation in all areas must be continued. Moreover, thefundamental role of the process of integration into the EU and NATO in offering the peoples of theregion the prospect of a common destiny within the European and Euro-Atlantic family cannot beoverstressed.

C.

STATE FRAGILITY: THE CASE OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA18

66. Although the process of institutional consolidation is well advanced in most of the countries inthe region, recent developments in Bosnia and Herzegovina demonstrate the continuing fragility ofthe institutions.67. The present Constitution, in Annex 4 to the Dayton Accord, establishes a weak and dividedState under close international supervision, in which two Entities – the Federation ofBosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska and three constituent populations –Bosno-Croat, Bosno-Serb and Bosniac - coexist. Central State attributes are reduced to aminimum and a whole series of instruments, such as the right of veto when vital interests areaffected, seek to prevent one community from dominating the others.68. Substantial reforms were nevertheless introduced during the years after the end of the war,inter aliato strengthen central institutions. The creation of a common currency, a common customsarea and common indirect taxation were important stages in progress towards the unification of thecountry. Defence reform may also be regarded as a major success. However, this process of Stateconsolidation has been slow and difficult and many reforms could not have succeeded withoutstrong pressure exerted by the international community.69. Furthermore, the rejection in April 2006 by two votes or so of the draft revised Constitutionopened up a new phase, marked by a clear slowdown in the reform process, which continuestoday. Constitutional reform is still blocked. Negotiations in Butmir in the autumn of 2009 underAmerican and European mediation seeking to break the deadlock were unsuccessful. In addition,in December 2009 the European Court of Human Rights confirmed – in the case of Sejdic andFinci v. Bosnia and Herzegovina – that the present provisions regarding elections to thePresidency of the Republic and to the House of Peoples establish a discriminatory regime andtherefore conflict with the European Convention on Human Rights19. The Working Group set up bythe Parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina to bring the Constitution into line with the Court’sdecision has not yet managed to reach agreement. Because of this continuing blockage ofconstitutional reform, the October elections were again held on the basis of the constitutionalframework established by Dayton.70. The delay in implementing essential reforms and the worsening political climate in thecountry have led the international community to postpone the closure of the Office of the HighRepresentative several times. However, the powers of the latter are being disputed with increasingvigour, especially in the RS, where the authorities are contemplating holding a referendum in RSterritory, the aim of which would be to measure the population’s support for the powers of the HighRepresentative20. The international community has strongly condemned this approach, as beingagainst the Constitution and in breach of the Dayton Accord.18

19

20

On this subject see,inter alia,the general report prepared by Vitalino Canas (Portugal) for thisCommittee in 2006 “Bosnia and Herzegovina. Prospects for the post-Dayton era”[164 CDS 06 E rev. 1], as well as the Report of the Rose-Roth Seminar held in Sarajevo in March2009 “South-Eastern Europe: from Dayton to Brussels” [092 SEM 09 E].These provisions state that only representatives of the three constituent peoples are eligible for theseoffices, thereby excluding any candidacy by,inter alia,Bosnian citizens belonging to otherethnolinguistic minorities.On 10 February 2010 the RS parliament passed a law which opens the way to such a referendum.However, no date has yet been set, neither has the precise question been defined. The RS authoritieshave also brought up the idea of a referendum on Bosnia and Herzegovina joining NATO. The Prime

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

17

71. Bosnia and Herzegovina had passed an important milestone on the way to Euro-Atlanticintegration in April 2010, when the North Atlantic Council decided to grant it a Membership ActionPlan, in recognition of progress in the destruction of surplus stocks of arms and the decision toincrease the Bosnian contribution to the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan.However, the Plan will be activated only when the defence property issue has been resolved. Thisissue is highly politicised, because the positions taken by the leaders of the various communitiesdiffer fundamentally.2172. This is a clear illustration of the way in which technical issues in Bosnia and Herzegovina canbe caught up in political debates and in which political blockages may in the end affect evenreforms regarded as successful up to that point, such as defence reform.73.In this context the general elections on 3 October 2010 gave rise to great expectations. Thepopulation was called upon to elect its representatives in six simultaneous elections, two atnational level and four at Entity level: election to the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina;election of members of the House of Representatives of Bosnia and Herzegovina; election to thePresidency and Vice-Presidency of RS; election to the RS National Assembly; election to theFederation House of Representatives; election to the 10 Cantonal Assemblies of the Federation.74.These elections provided a good illustration of the ambiguities in the present situation. Onthe one hand, the official observers welcomed the general smooth running of the elections. On theother, the campaign and the election results revealed divergent trends within the variouscommunities.75. Regarding the organisation of the elections, the International Election Observation Mission(IEOM) – including representatives of the OSCE, the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly, the Councilof Europe Parliamentary Assembly and the NATO PA – considered that the elections were“generally in line with international standards for democratic elections” and welcomed “furtherprogress for Bosnia and Herzegovina”, although “certain areas require further action”. In particularthe international observers noted that because of ethnic criteria affecting voting and eligibility, theelections had once more been organised in breach of the European Convention of Human Rights.76.Moreover, the IEOM stresses that the campaign was generally calm, although occasionallymarked by nationalist rhetoric and inflammatory statements by certain candidates. Whilecandidates did address economic and social issues and European integration, “constitutionalissues and underlying ethnic divisions remained omnipresent”.77.The election results are also mixed. The official turnout of 56% at the national level is thehighest recorded since 2002 (one and a half points higher than the 2006 general elections).However, while the voters in the Federation seem to have opted for change by supporting partiesregarded as moderate – the Party of Democratic Action (SDA) and the Social Democratic Party(SDP) – RS voters confirmed domination by Milorad Dodik’s Alliance of Independent SocialDemocrats (SNSD)22. In particular the change is most marked in the Bosniak electorate, with a lossof momentum by the Party for Bosnia and Herzegovina (SzBiH) of Haris Silajdzic, the BosniakPrime Minister during the war and outgoing Bosniak member of the country’s Collegial Presidency,

21

22

Minister of the RS, Milorad Dodik, has nevertheless rejected fears of a referendum on the secession ofthe RS as unfounded.In September 2010 the RS Parliament had discussed a law aimed at resolving the issue of ownershipof State assets in the entity’s territory, a unilateral approach condemned by the High Representativeand the Peace Implementation Council.According to final results, Mr Dodik was elected to the Presidency of the RS with 50,5% of the votes.The SNSD remains the first party in the RS Assembly, but with slightly less votes than in the 2006elections.

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

18

supplanted by the SDA, which saw its candidate, Bakir Izetbegovic, elected to the Presidency23.78. Final results were declared on 2 November 2010. It will probably take several months moreto form the government.24Fifteen years after the end of the conflict, Bosnia and Herzegovina againseems to be at a watershed. The post-electoral period will give important guidance as to thewillingness and capability of the political class to go resolutely into the post-Dayton phase. All theinternational observers have called for the rapid resumption of the reform process, which isessential both for the future of the country on the domestic level and for its future integration intoEuro-Atlantic structures. In particular it is essential to relaunch the constitutional reform process assoon as possible.79. The EU and NATO are faced with a difficult choice. Up to now the EU has adhered to strictconditionality, whereby an application by Bosnia and Herzegovina to join could be accepted onlyonce the Office of the High Representative had been dismantled, which assumes compliance withthe 5 objectives and the 2 conditions set out by the Peace Implementation Council.25At the sametime, some observers deplore the fact that this strict conditionality has not had the desiredincentive effect and state that perhaps a more targeted approach which makes a clearer distinctionbetween technical and political issues would be preferable. Thus relaxing the conditions forobtaining visas and the prospect of visa exemption for Bosnian citizens are widely welcomed ashaving encouraged the authorities to take the necessary steps. The regional dimension hasunquestionably been an important factor. The same targeted approach has been adopted byNATO, with the condition that the issue of defence property must be resolved in order to activatethe Membership Action Plan.80. By its vote, a substantial part of the Bosnian electorate has declared that it expects itselected representatives to tackle the most important economic and social problems. Theopportunity offered by these elections to refocus on these problems must be seized. It meanssomething that it is in the Federation in particular that the call for political renewal has elicited thegreatest response. The Federation suffers from many of the same ills as the State, and thesituation, both political and economic and social, feels their effects.26It is therefore essential torelaunch the reform process at both central and entity level, in order to avoid a widening gapbetween the Federation and the RS and the resulting creation of a new imbalance bringinginstability.81. Urgent institutional reforms are required for the Bosnian political system to be viable.However, it is possible and desirable to disconnect the timetable and framework for institutionalnegotiations from those for governmental institutions, to avoid, as far as possible, technical issues23

2425

According to final results, Mr Izetbegovic was elected with 34.8%, while Mr Silajdzic came third with25.1% of the votes (as against 62.8% in 2006). Zeljko Comsic (SDP), the outgoing Croat member ofthe Presidency, was re-elected with over 60% of the votes (as against 39.5% in 2006), as wasNebojsa Radmanovic (SNSD), the outgoing Serb member, re-elected with 48.9% of the votes (asagainst 53.2% in 2006).According to estimates by the High Representative, this will not occur before February 2011.Objectives: 1) acceptable and sustainable resolution of the issue of apportionment of propertybetween State and other levels of government; 2) acceptable and sustainable resolution of defenceproperty; 3) completion of the Brcko final award; 4) fiscal sustainability; 5) entrenchment of the rule oflaw. Conditions: 1) signing of the Stabilisation and Association Agreement with the EU; 2) stability inthe political situation. The General Affairs Council meeting in Brussels on 7 December 2009 reaffirmedin its conclusions “that it would not be in a position to consider an application for membership byBosnia and Herzegovina until the transition of the OHR to a reinforced EU presence has beendecided. While underlining that constitutional reform is not part of the conditions for closure of theOHR, Bosnia and Herzegovina needs to undertake an initial set of constitutional changes to create afunctional state and align its constitutional framework with the European Convention on HumanRights.”On the situation in the Federation, see the detailed report by theInternational Crisis Group “Federationof Bosnia and Herzegovina – A Parallel Crisis”,28 September 2010.

26

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

19

again becoming hostage to political blockages. The EU and NATO can encourage advances inparallel on these two fronts by a more targeted approach. Having regard to developments in thepolitical landscape in the Federation, the attitude of the RS will probably be the decisive factor. It isto be hoped that now the elections are over, campaign rhetoric will give way to a more constructiveapproach and that no political force is prepared to be responsible for an isolatedBosnia and Herzegovina, falling behind in the process of Euro-Atlantic integration. Resolution ofthe defence property issue would be a first strong signal, allowing the country to take a major stepon the way to integration into NATO.D.KOSOVO

82. After nine years of international administration in Kosovo and two years of fruitlessnegotiations on the final status of the province, on 17 February 2008 the Kosovar authoritiesdecided to proclaim the independence of Kosovo27. For Pristina and the States which haverecognised the independence of Kosovo this declaration was the logical culmination of a processand the only viable long-term solution. On the other hand, Belgrade has roundly condemned thisunilateral step. Thus the effect of Kosovo’s declaration of independence has also been to createfresh uncertainties and difficult challenges, which are still unresolved two and a half years later.83. First there is legal uncertainty, because the declaration of independence of Kosovo shatteredthe consensus that had existed up to that point within the international community on Kosovo.Divisions are apparent within the Alliance and the EU, as well as in the region. Thus, on11 October 2010 the independence of Kosovo had been recognised by 70 of the 192 UN memberStates, including 22 of the 27 member States of the European Union, 24 of the 28 members ofNATO28and 4 of the 6 successor States of the former Yugoslavia29.84. Serbia has brought the issue of the legality of Kosovo’s declaration of independence into thelegal arena by initiating Advisory Proceedings in the ICJ30. The Court gave its Opinion on22 July 2010, finding by ten votes to four that “the declaration of independence of 22 February2008 did not violate general international law”. The judges adopted a very narrow approach to thequestion put to them, going through the rules of international law that applied to Kosovo at the timeof the events31, and taking the view that the authors of the declaration were not bound by any ruleprohibiting adoption of such a declaration. The Court did not consider it necessary to examine thequestion whether international law conferred on Kosovo a positive right to declare itsindependence, or the more general issue of the right to secession.85. Although the Court’s Opinion strengthens Pristina’s position, it has not had the impactexpected by the Kosovar authorities, who were hoping for a new wave of recognitions.32Nonetheless it has the great merit that it clarifies a certain number of legal issues, and in particularsends the ball back into the polticians’ court.86. The security situation has remained relatively calm, in contrast to the fears that had precededthe declaration of independence. Nonetheless, “the potential for volatility and instability, especially

27

282930

3132

On the stages which led to independence, seeinter aliathe two reports “Kosovo and the Future ofBalkan security” [163 CDS 07 E rev. 1 and 155 CDS 08 E] prepared by Vitalino Canas (Portugal) forthis Committee in 2007 and 2008.The 4 NATO member States which have not recognised the independence of Kosovo are Greece,Romania, Slovakia and Spain. In the EU it is the same four, plus Cyprus.Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina have not recognised the independence of Kosovo.An Advisory Opinion concerning “Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral Declaration ofIndependence by the Provisional Institutions of Self-Government of Kosovo” was requested by theUnited Nations General Assembly in October 2008.General international law, Security Council resolution 1244 and the Constitutional Framework adoptedon behalf of UNMIK by the Secretary General’s Special Representative.Honduras is the only State to have recognised Kosovo after the publication by the Court.

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

20

in northern Kosovo, cannot be underestimated.”33Isolated incidents and violence interethnic innature continue to nourish a climate of insecurity and tension, particularly in Northern Kosovo. Theyear 2010 was marked by a number of incidents: confrontations between Serb and Albaniandemonstrators on the bridge at Mitrovica on the occasion of elections organised by Belgrade inNorth Mitrovica on 30 May; demonstrations and violence on the opening of a Kosovar LocalGovernment and Internal Affairs Ministry office in Bosniak Mahalla on 2 July, leaving one persondead and 12 injured; shots fired at a Serb member of the Kosovo Assembly in front of hisresidence in North Mitrovica on 5 July; and interethnic violence in Mitrovica following Serbia’sdefeat at the basketball world championship, leaving one EULEX French gendarme and severalKFOR soldiers injured. Moreover, several Serb families which had moved back to Zac/Zllac inwestern Kosovo in March were subjected to threats and violence. Although the trend is not towardsan increase in the number of incidents, these events indicate the suspicion – even distrust – thatcontinues to affect relations between communities.87. The Kosovo Police Service (KPS) has a key role to play in this, both by demonstrating itsability to perform its duties in maintaining law and order in the service of the population and also byacting as a vehicle for integrating the various communities. It is therefore essential to continue withthe reinstatement of the Serb police officers who had left the KPS after the February 2008declaration of independence.34Moreover, the transfer of responsibility for protecting Serb religiousand cultural sites in Kosovo from KFOR to the KPS will be an important test for the latter, so it isnecessary to ensure that this is done under the best possible conditions, taking into account inparticular the concerns of local Serb populations and the Orthodox Church.35The gradualreduction in the KFOR presence as part of the transition to a deterrent presence must also bemanaged with care.88. The Kosovar authorities have sought to establish the legal framework and institutions of anindependent State, drawinginter aliaon the principles and priorities set out in the Ahtisaari Plan.They have also embarked upon a wide-ranging process of political, economic and social reforms.Nevertheless, these measures have come up against the weakness and the problemscharacteristic of new institutions, among which may be mentioned, notably corruption that is stilltoo widespread36and limited administrative capabilities, which mean in practice that many reformsare implemented only in part. Moreover, the rejection by part of the population of the legitimacy ofPristina’s institutions, as well as the lack of universal recognition of Kosovo’s independence at theinternational level, also restrict the capacity of the Kosovar authorities to exercise in full thejurisdictions and powers to which State institutions are normally entitled. Consequently, manyproblems remain in essential areas such as strengthening the rule of law. To this should be addedstructural difficulties and weaknesses in the Kosovar economy, and in particular a rate ofunemployment that remains particularly high.

3334

35

36

Report of the United Nations Secretary-General of 29 July 2010, S/2010/401, para. 50.317 of the 325 officers who had ceased activity after the declaration of independence were reinstatedin 2009. According to the Kosovo Police Service’s official statistics, the Service includes 7,000 policeofficers, of which 85.8% are Albanian and 9.4% are Serb.An initial transfer began in March 2010, for the protection of the Gazimestan monument. Responsibilityfor security at the Gracanica monastery was also transferred to the KPS in August 2010. Each ofthese transfers must be specifically approved by the North Atlantic Council on the basis of anassessment of the situation on the ground. Transferring the protection of religious and cultural sites isa particularly sensitive area for the Kosovo Serb community, which still retains a very vivid memory ofthe March 2004 riots. Some 30 Serb churches and 2 monasteries had been destroyed or damagedduring these riots, which had also cost the lives of twenty persons and injured some 900 others, andcaused some 5,000 Serbs to quit Kosovo. During a visit by a NATO PA delegation to the Gracanicamonastery in June 2010, the Serb Bishop Teodosije had repeated again that only KFOR had the trustof all the communities enough to be able to perform this task of protecting religious sites. See thereport of this visit [194 DSCFC 10 E].However, we can point to recent efforts by the government in Pristina, supported by EULEX, to stepup the campaign against corruption.

208 CDSDG 10 E rev 1

21