NATO's Parlamentariske Forsamling 2010-11 (1. samling)

NPA Alm.del Bilag 5

Offentligt

SCIENCE ANDTECHNOLOGY225 STC 10 E bisOriginal: English

NATO Parliamentary Assembly

CLIMATE CHANGE:POST-COPENHAGEN CHALLENGES

SPECIALREPORT

PIERRECLAUDENOLIN (CANADA)SPECIALRAPPORTEUR

International Secretariat

14 November 2010

Assembly documents are available on its website, http://www.nato-pa.int

225 STC 10 E bis

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I.II.III.

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1THE SCIENCE OF CLIMATE CHANGE ................................................................................ 1COPENHAGEN SUMMIT ON GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE................................................. 4A.FROM KYOTO TO THE COPENHAGEN ACCORD ..................................................... 4B.WHAT WAS HOPED FOR AND WHAT WAS ACHIEVED ........................................... 5C.DIFFERING NATIONAL AND REGIONAL PERSPECTIVES........................................ 71.The developed countries ..................................................................................... 72.Developing countries: BASIC............................................................................... 83.Developing countries: the African Group and the Alliance of Small Island States 9THEPOST-COPENHAGENSTRATEGY:PRELIMINARYASSESSMENTANDRECOMMENDATIONS.......................................................................................................... 9

IV.

225 STC 10 E bis

1

I.

INTRODUCTION

1.The intense climate change negotiations that took place in Copenhagen in December 2009brought together the top heads of states, ministers and state officials in an attempt to reach alegally binding treaty to succeed the Kyoto Protocol. The Copenhagen Accord was equallydescribed as an absolute failure and lauded as a positive and significant step forward to slowing orreversing the phenomenon of global warming.2.The Copenhagen Accord set the goal of limiting the rise of global temperatures by 2�C,compared with pre-industrial levels; it provided for an increase of financial aid for the developingnations, emissions transparency via international monitoring, and a review of progress by 2015.Perhaps, the most important and positive outcome of the Summit is that its final document wasendorsed by all major emitters, including the United States and China.3.However, the Copenhagen Accord was taken “note of”, rather than properly adopted by theparties. It is non-binding and does not entail a path towards a legally binding agreement.Moreover, the Accord is incomplete in many areas and achieved much less than what was initiallyhoped for. It has no long-term global emission reduction target, nor does it establish peaking datafor emissions, not even for the developed countries.4.The NATO Parliamentary Assembly, and its Science and Technology Committee inparticular, has been constantly discussing climate change and its global security implications. TheAssembly has been consistent in its support for a concerted global response to this globalchallenge. NATO parliamentarians also supported the notion that climate change must occupy animportant place on the Alliance’s agenda and be included into the new NATO Strategic Concept.Although the Assembly has adopted several climate change-related reports and policyrecommendations in recent years, the Copenhagen Summit has been a milestone event thatrequires a fresh look at the new global climate policy landscape. In particular, the Summit raisesthe question of whether the UN-led climate effort is still viable, or if other – national/bottom-up orregional – approaches provide a more feasible alternative.5.Another major recent development is the partial reopening of the scientific debate behindclimate change, once seemingly closed by the release of the 2007 report by the IntergovernmentalPanel on Climate Change (IPCC). The so-called “Climategate”, the scandal involving the leak ofconversations between some of the world’s top meteorologists and researchers from theUniversity of East Anglia, United Kingdom (although they were subsequently cleared by a specialinquiry panel), made climate change sceptics more vocal in discrediting IPCC’s scientific work.Some of the intercepted e-mails indicated that there were attempts to manipulate or suppressdata, which is incompatible with scientific practice. The scandal has become an important factorinfluencing Copenhagen and post-Copenhagen negotiations. Therefore, this paper will begin witha discussion on the basic scientific premises of the climate challenge.

II.

THE SCIENCE OF CLIMATE CHANGE

6.The “Climategate”, coupled with the effects of the global economic recession, hasundoubtedly reduced the public support for urgent action to tackle global warming. Recent polls1indicate that 10-15% of British people switched sides and joined the climate sceptics’ camp.According to a 2010 Gallup poll, roughly half of “moderate” Americans believe that the seriousness

1

BBC Climate Change Poll, February 2010.http://news.bbc.co.uk/nol/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/05_02_10climatechange.pdf

225 STC 10 E bis

22

of the climate challenge is exaggerated, compared with around 35% two years ago . Several flawswere detected in the 2007 IPCC report, particularly the poorly substantiated claim that theHimalayan glaciers would melt down by 2035. Alternative theories attempting to explain globalwarming (or absence thereof) are constantly being offered.7.However, the science of global warming is more than just the studies of those people whoreceived the Nobel Prize in 2007. Occasional mistakes in these studies cannot negate theth150 years of research by the most reputable scientists, starting with the 19 –century physicistsJohn Tyndall and Svante Arrhenius. The mechanics of the greenhouse effect and the correlationbetween the levels of CO2and global temperatures are well–understood and universally accepted.It is known that upon reaching the earth’s surface, solar radiation is converted into heat energy,which emits infrared rays back into space. The molecules of greenhouse gases – water vapor,carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and ozone – capture some of the infrared radiation,thereby warming up the atmosphere. This effect is central to life on our planet, which wouldotherwise be unbearably cold.8.By analysing tree rings, air bubbles trapped in ice, pinecones, coral reef cores, oceanicsediments and other proxies, scientists found a way to establish how our planet’s averagetemperature changed over hundreds of thousands of years. They discovered that while theaverage temperature constantly fluctuated over millennia, causing ice ages and periods of warmth,the current rise is quite unique. This uniqueness is reflected in the renowned “hockey stick” graph,thwhose upward incline indicates how rapidly temperatures were rising in the 20 century. Thereconstruction of trends in greenhouse gas concentration in the atmosphere (mostly by analysingdeep layers of polar ice) unambiguously shows that these trends coincide remarkably withfluctuations of average global temperatures. This conclusion is based on data that has beencollected by independent groups of scientists in different parts of the world. Therefore, the focusof climate sceptics on certain flaws in the milestone 1998 study by Michael Mann and his team isinsufficient to prove their point. There are many other “hockey sticks”.

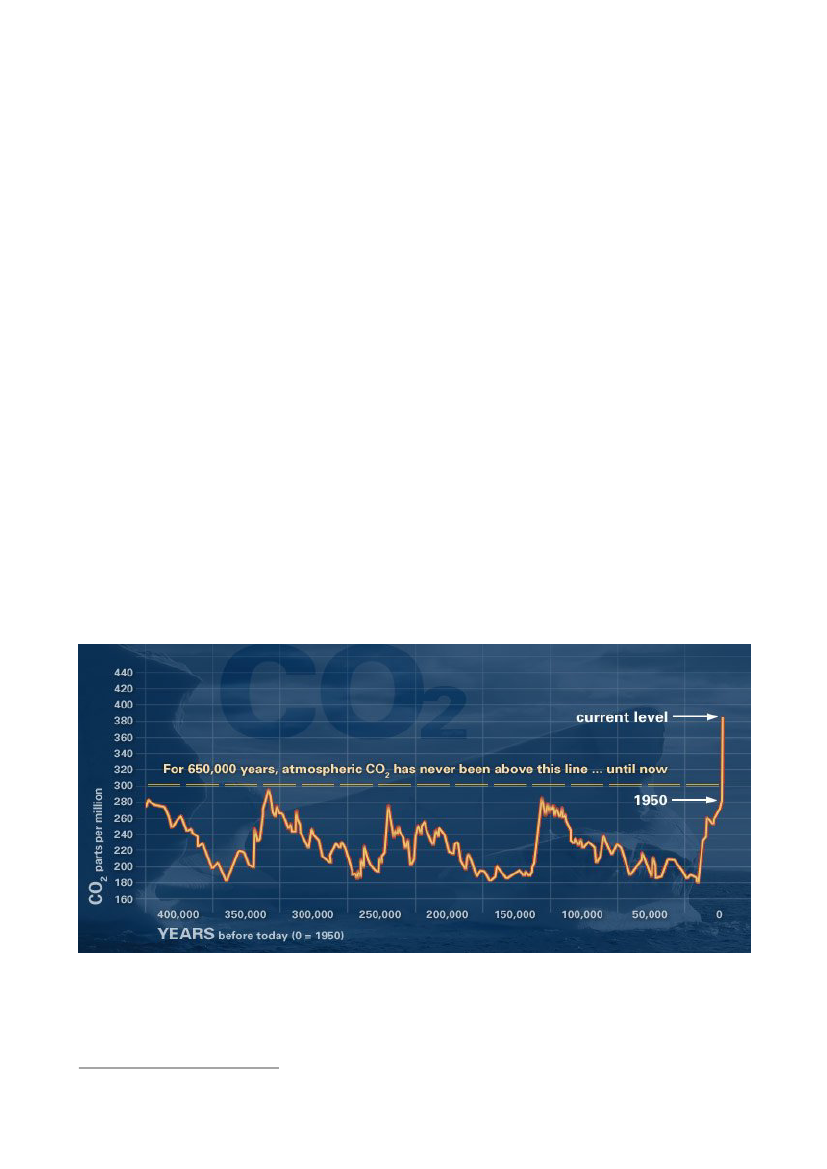

Figure 1. Evidence that atmospheric CO2has increased since the Industrial Revolution(Source: US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - NOAA)

9.The fact that the rise of greenhouse gas concentration translates into warmer temperaturesthis alarming: the volume of CO2has increased from 280 parts per million (ppm) in the 18 century,to 380ppm in 2010. Under the current trends, the amount of CO2in the earth’s atmosphere might2

“Let It Be”, The Economist. 29 July 2010.

225 STC 10 E bisst

3

double in the course of the 21 century, if compared to pre-industrial levels. Back in 1896,Svante Arrhenius calculated that doubling the amount of CO2would result in an increase in globaltemperatures of almost 6�C, an estimate which is still valid today.10. Compared to the mid-19 century, our planet is already 0.8�C warmer (most of the increasethoccurred during the second half of the 20 century). However, we are still in the initial stages ofglobal warming. The objective of the maximum 2�C rise by the end of this century is unlikely to beachieved, unless drastic reductions of emissions are implemented. Even if the global economystopped emitting carbon altogether, the temperatures would still rise for decades and possiblycenturies due to the role of the ocean. Currently, global temperatures do not rise as fast as theCO2concentration as the ocean absorbs and stores almost 80% of all surplus heat. This heat willkeep our planet warmer in the foreseeable future. In addition, the world’s natural CO2absorptioncapacity will diminish with time, potentially resulting in the acceleration of global warming.11. The changing climate is having a significant impact on sea levels because the oceanexpands as it gets warmer. The melting of glaciers and continental ice sheets also contributes torising seas. By analysing ocean sediments and coral reefs, scientists discovered that, for the lastseveral thousand years, the average rate of sea rise was 0.1-0.2mm a year (this natural process isrelated to the fact that our planet is currently in the inter-Ice Age period). However, in theth20 century the rate increased to 1.5mm per year, and since the 1990s it reached more than33mm. It goes without saying that such a dramatic acceleration of this historic trend is alarming.12. Thanks to laser and other modern techniques, we now know that for the last 150 yearsmountain glaciers have been melting at the rate of 50m per decade. The melting of polar ice capsis more difficult to put into a historic perspective due to the absence of reliable data. Satellite datashows a startling trend of Arctic ice sheets shrinking by 7% per decade. The average depth ofArtic ice has also shrunk considerably, from 3.64m in 1980 to less than 2m in 2008. This datacovers a period of a mere 30 years, however, and further observation is needed to claim that this4trend is not temporary. The faster pace of warming in the Arctic is entirely justified scientifically,since shrinking ice caps result in more solar radiation being absorbed by the earth’s surface.13. Climate change has a direct impact on precipitation patterns, harvests and flora and fauna.Less directly, it impacts weather events, including hurricanes, floods, draughts and heat waves. Awarmer planet essentially means that it has extra energy, which can display itself in various ways,including through more violent storms. It has been established that the number of high intensitythcyclones has markedly increased in the second half of the 20 century, coinciding with anacceleration of global warming. Formation of cyclones is a very complex process and notexclusively climate change-driven, but it is widely agreed that climate change will increase thelikelihood of such events.14. Climate contrarians generally agree that the planet is getting warmer. However, two keypremises are being questioned: 1) that the current warming is caused by the greenhouse effect;and 2) that it is man-made.15. In terms of the former, contrarians refer to the fact that solar activity has intensified duringththe course of the 20 century. However, the models, which are based solely on solar or theearth’s orbital factors, fail to explain the observed historic average temperature trends.Furthermore, the ‘solar theory’ cannot explain the fact that temperatures only increased in thetroposphere (the layer closer to the surface), while the stratosphere has become cooler (this isth

3

4

Le réchauffement est-il sûr? (‘Is global warming real?’), Céile Bonneau and Yves Sciama.Science&Vie, March2010, p.51.Ibid.,p. 44.

225 STC 10 E bis

4

perfectly logical according to the “greenhouse theory”). Ocean warming patterns and the fact thatwarming is greater over land than over sea also speak in favour of the greenhouse model.16. It is also claimed that our planet experienced a similarly warm period around 900-1200 AD,ththfollowed by a Little Ice Age in the 16 -18 centuries. However, these fluctuations were regional innature and did not reflect the global trend. Moreover, the fact that solar and other natural factorscertainly influenced climate changes in the past does not disprove the assumption that the currentwarming is caused mainly by human activity.17. Some argue that while the current warming was caused by an increased concentration ofgreenhouse gas in the atmosphere, this increase occurred because of natural factors, such asvolcanic eruptions. However, studies show that the volume of CO2produced by humans burningfossil fuels (about 30 billion tons a year) is 130 times greater than emissions from volcanic activity.The anthropogenic origin of most of the surplus CO2is evident from isotope analysis. It is alsoargued that water vapour, not CO2, is the most prevalent greenhouse gas. However, the higherconcentration of water vapour in the atmosphere is, in fact, a result of warmer temperatures, not5the original cause of it. Solar and other natural factors certainly do play a role and are included inall major climate models, but their impact most likely accounts for less than 10% of the overall6impact.18. Climate change is certainly a phenomenon that is not yet entirely understood by scientists.A number of uncertainties still need to be addressed, including the role of clouds, aerosols, cosmicrays, methane emissions and the weakening of the oceanic thermohaline circulation.Nevertheless, the key findings of the 2007 IPCC report remain valid and climate changerepresents a challenge that requires urgent and concerted international action.

III.A.

COPENHAGEN SUMMIT ON GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGEFROM KYOTO TO THE COPENHAGEN ACCORD

19. The Copenhagen talks took place as part of the UN Framework Convention on ClimateChange (UNFCCC), adopted at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The stated aim of theUNFCCC was to stabilise the levels of greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere, which couldpossibly cause anthropogenic interference with the climate system. These aims were establishedas part of the Kyoto Protocol that was signed in 1997 and came into effect in 2005. The first phaseof the Kyoto Protocol expires in 2012, therefore a fresh round of negotiations is now crucial for anew treaty that would be more all-encompassing than the Kyoto Protocol.20. Being the only legally binding climate agreement ever signed by a limited number ofcountries, the future of the Kyoto Protocol stirred much controversy and disagreement among theparticipant countries. The targets for greenhouse gas emission cuts, as set in the Kyoto Protocol,applied only to a small set of developed countries, exempting the developing countries, amongwhich were China and India whose emissions have risen sharply since the Kyoto Protocol wassigned; China’s emissions, for instance, have more than doubled since 2000, surpassing even theUnited States. More significantly, the Kyoto Protocol was never signed by the United States on thegrounds that the 5% reduction of emissions, as required by the Protocol, would “wreck theAmerican economy”, whilst freeing the developing countries from any obligations.

5

6

“Seven Answers to Climate Contrarian Nonsense”, John Rennie.Scientific American.30 November 2009.“The Physical Science Behind Climate Change”, William Collins.Scientific American.6 October 2008.

225 STC 10 E bis

5

21. The Copenhagen Summit represented an opportunity to rectify the shortfalls of the previousclimate change arrangements. One of the issues was the legal form of the agreement, i.e. if thenew agreement should represent an extension of the Kyoto Protocol with increased commitmentsby the developed countries, or if a completely new agreement should be concluded. The heart ofthe discussion included the burden sharing between the developed and developing nations, interms of both finances and emission level cuts. The main argument put forward by the developingcountries, led by China and India, is that the developed, industrialised nations should bear thehistoric responsibility for the climate changes and commit themselves to deeper carbon emissioncuts before expecting the poor nations and China to implement measures that would jeopardisetheir economic growth. Thus, the developing countries essentially tried to retain the KyotoProtocol’s principle of “common but differentiated responsibility”.22. At the same time, many American politicians warned about the danger of concluding a poorlydesigned agreement, whereby the developed countries would bear a burden that has little impacton the fight against global climate change. In other words, any commitments that developedcountries undertake will still have to be complemented with efforts undertaken by the developingnations and, in particular, China and India. Since 1990, carbon emissions from these twoeconomies have risen steeply, making China the world’s largest emitter. Therefore, all efforts bythe developed countries will be offset, if the developing countries do not undertake similar actionsand continue with the same pace of carbon-intensive industrialisation.23. A number of ideas were put forward by individual countries, international organisations andthe expert community on key elements of the post-Kyoto framework. For its part, theNATO Parliamentary Assembly suggested the following principles:1.2.3.4.universal membership (bringing in the United States and Australia is vital);emission reduction targets for all countries, not just for the industrialised world;deeper emission cuts in the post-Kyoto framework for the industrialised nations;industrialised nations have to achieve greater progress in reducing emissionsdomestically, instead of relying too much on acquiring credits through “flexiblemechanisms”;new initiatives are needed to help the communities that are already at risk;encouraging further investment in “green” technologies, particularly renewables,carbon capture and storage; andlaunching new energy efficiency initiatives.

5.6.7.

B.

WHAT WAS HOPED FOR AND WHAT WAS ACHIEVED

24. The Assembly’s position essentially coincided with that of the UNFCCC Executive SecretaryYvo de Boer, who has listed four essentials to a new treaty. These four issues were the mainpoints of discussion during the Copenhagen Summit:1.2.3.4.By how much are the industrialised countries willing to reduce their emissions ofgreenhouse gases?By how far are the major developing countries such as China and India willing to go tolimit the growth of their emissions?By how far is the help needed by developing countries to engage in reducing theiremissions and adapting to the impacts of climate change going to be financed?By how is that money going to be managed?

25. In the context of changing US leadership, hopes ran high that the final outcome of theCopenhagen Summit would lead to a legally binding treaty entailing collective commitment todeeper emission cuts to hold the temperature rise to 2�C, or possibly even to 1.5�C. A draftproposal listed by the host country, Denmark, stated that the world greenhouse gas emissions

225 STC 10 E bis

6

should drop by 50% by 2050 from the 1990 levels, and the overwhelming responsibility for gasreduction should be undertaken by the developed countries. Nonetheless, to the greatdisappointment of the developing countries and environmentalists, the Copenhagen Summitclosed with a rather weak and non-binding agreement that seeks to limit temperature rises butdoes not include specific emission targets.26. The Accord’s key achievement is the commitment to reduce global greenhouse-gasemissions in order to maintain the 2�C benchmark. However, the terminology used in the Accorddoes not identify this goal as a formal target. Instead, it simply notes that the Summit “recognizing7the scientific view that the increase in global temperature should be below 2 degrees celsius”.27. Also, the Accord does not clearly identify a year when the global carbon emissions shouldpeak. This point was contentiously debated during the Summit. The setting of a global target datefor emission cuts was outwardly rejected by China, India, Brazil and South Africa. The argumentput forward by the South African’s chief climate negotiator Alf Wills was that the developed nations8must do much more to immediately reduce their emissions before they set global targets. For thisreason, the Accord only states that the carbon emissions should peak as soon as possible,9recognising that the peaking will need a longer time frame for the developing nations.28. The 1 of February 2010 was the deadline by which countries were asked to submit theirdeclarations to pledge to curb carbon emissions by 2020. Nonetheless, this deal did not includepenalties for countries that did not submit targets by the set date or those which fall short ofmeeting their targets. Fifty-five countries, responsible for 80% of global emissions, including thestUnited States, China and India, met this 1 February deadline.29. The second key issue agreed upon in the deal was that, between 2010 and 2012,US$30billion would be provided by the developed nations to the developing nations, and aprojected US$100billion would be mobilised annually by 2020. Such funding will be directed toprojects that tackle climate change mitigation and deforestation, and will come from various public,private, multilateral and bilateral sources.30. On the negative side, the agreement never envisaged how these additional funds will beraised and how the financial burden sharing will be divided among the developed nations.Furthermore, it was not clarified how the developing nations could access the funds. Thegovernance structure of the overseeing body, the new Copenhagen Green Climate Fund, was alsonot settled.31. The governance structure and mechanisms were also only partially approved. Besides theCopenhagen Green Climate Fund, the mechanisms which participating governments agreed toestablish included: the Technology Mechanism (to accelerate technological development andtransfer in support of action on adaptation and mitigation which will be guided by a country-drivenapproach and which will be based on national circumstances and priorities, and the Mechanism forReducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD).32. More importantly, the Agreement states that all internationally funded climate changemitigation actions undertaken by the developing countries, will be subject to internationalMonitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV). Mitigation measures which are not internationallyfunded will be subject to national reporting every two years. The developed countries’ mitigationactions will also undergo international MRV.st

789

Copenhagen Accord, UN Framework Convention for Climate Change, 18 December 2009.“Big developing states reject Copenhagen climate plan”, Reuters, 2 December 2009.Copenhagen Accord, UN Framework Convention for Climate Change, 18 December 2009.

225 STC 10 E bis

7

33. The MRV measures, however, cannot be applied if mitigation actions are not internationallyfunded. The downside of this is that many non-internationally funded actions by wealthierdeveloping nations, such as China, will not be subject to international scrutiny. Also, the functionand nature of the Technology Mechanism, the REDD Mechanism or the Copenhagen Green10Climate Fund are not clearly defined.34. It was agreed that the progress review to assess implementation of the CopenhagenAgreement would take place in 2015. The review is set to take place almost a year and a half afterthe IPCC drafts the next scientific assessment of global climate change.

C.

DIFFERING NATIONAL AND REGIONAL PERSPECTIVES

35. The main divisions during the negotiations at the Copenhagen Climate Change Summit werebetween the developed and developing countries. However, other nations also established officialblocks, from which they could strengthen their negotiating position.1.

The developed countries

36. The European Union attempted to act as a unified entity at the Copenhagen Summit, makinga commitment to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 20% by 2020, in comparison to the 1990levels. It also later committed to reducing its emissions by an additional 30%, if the otherindustrialised countries would undertake the same obligation. However, it was widely believed thatthe EU’s role in negotiations was reduced to that of a secondary player and that the CopenhagenAccord was essentially a deal between the United States and the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India andChina) countries. The EU is the undisputed global leader in terms of environmental awareness andreadiness to impose rigorous emission reduction targets, which makes it a non-problematic – but,paradoxically, also less relevant – negotiating partner.37. The other non-EU industrialised nations, also known as the Umbrella Group, include theUnited States, Russia, Japan, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Norway and Iceland. The pivotalplayer in this group is the United States, and its behaviour was carefully observed, owing to thefact that the United States, as the biggest per capita global emitter, refused to sign the KyotoProtocol in 1997. The commitment made by the United States under the Copenhagen Accord wasto cut its greenhouse gas emissions by around 17% by 2020, compared with 2005. This is also11contingent upon the Congress ratifying climate change and energy security legislation. Thefurther greenhouse gas reductions envisaged by 2025 are to amount to 30%, and 83% by 2050.38. Japan’s targets for carbon reduction are 25% by 2020, in comparison to 1990, only on thecondition that all major countries follow suit. The Australian Parliament already twice rejected a billintroducing an emissions trading scheme, which would help to reduce the country’s carbon outputby between 5% and 25% of 2000 levels by 2020. Therefore, the Australian government has to lookfor other ways to meet this target.39. Canada has planned a gas emission cut of 20% by 2020 compared to 2006, which is equalto a 3% drop in comparison to the 1990 benchmark. The Canadian Parliament has passed anon-binding decision for a 25% cut, compared to 1990 emissions levels, whilst Quebec decided to12stick to the EU’s position.10

11

12

“Perspective on Copenhagen”, Report by Carbon Trust. 24 December 2009.http://www.carbontrust.co.uk/news/news/press-centre/2009/Pages/perspective-on-copenhagen.aspx“Climate Goal Is Supported by China and India”, John M. Broder.The New York Times.9 March 2010.http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/10/science/earth/10climate.html“World's nations set different climate protection goals”, 7 December 2009http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,,4967923,00.html

225 STC 10 E bis

8

40. Dmitry Medvedev committed Russia to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by between22 and 25% by 2020, from the 1990 levels, thus raising the 15% target. These numbers are stillnot officially confirmed and are on condition that the United States, China and others follow suit.Nonetheless, despite the general Russian scepticism on climate change, Dmitry Medvedevpromised to contribute around US$200million to a multi-billion fund to assist projects directed tothe reduction of greenhouse gas output of poor countries’.2.

Developing countries: BASIC

41. The G77 and China block, comprising 130 developing countries, maintains that theindustrialised countries should greatly decrease their emissions, whilst allowing G77 and China tocontinue developing their industries. Additionally, many of these countries called for financialpackages and technology to be provided by the developed countries for their climate-protectionprojects.42. China has announced that it plans to voluntarily decrease its “carbon intensity” by 40 to 45%by 2020, compared to its 2005 levels. This does not necessarily imply that China’s overall carbonoutput will decrease, the country simply planning to develop its economy faster than it will increaseits consumption of fossil fuels. In addition, China has set very high mandatory targets for wind,biomass and solar energy, calling for around 30GW from both wind and biomass energy by 2020.Its clean energy investments went up by 50% in 2009 and totalled US$36.4 billion, thus making13China the major power in world clean energy investments. Also, at Copenhagen, China accusedthe industrialised countries of outsourcing their carbon emissions to developing countries. As aresult, China is involved in carbon-intensive manufacturing on behalf of Western buyers. Thus, itdemanded that consumer countries, rather than producers, should take responsibility for carbonemissions generated by such industrial activities.43. India has also committed to reducing its carbon emissions by 20% in comparison to its2005 levels. This voluntary and non-binding measure is also contingent upon assistance by theinternational community. For both India and China, the Copenhagen Accord is likely to be viewedas a satisfying outcome for numerous reasons. First of all, the Accord did not compromise theirfundamental negotiating positions, including the opposition to imposing binding emission reductioncommitments upon developing countries. Even more importantly, from a long-term perspective,the positive outcome of the Copenhagen Summit is that both China and India managed toestablish themselves as de facto leaders of the newly-emerged “BASIC” group of countries (Brazil,South Africa, India and China), which had a considerable impact on the drafting of the14Copenhagen Accord.44. South Africa and Brazil have committed to voluntarily reduce their emissions by more than30% by 2020, compared to the projected level of emissions for that year, if business continued asnormal. Brazil mainly plans to achieve this goal by limiting deforestation in the Amazon basin. Interms of renewable energy, Brazil is making surprising progress. With around US$7.4billioninvestment in clean energy, Brazil has launched itself as second to China among the emerging15economies for investments in clean energy, and sixth among the G20.

1314

15

“CO2reductions slip down EU priority list”, EUobserver online, 15 September 2010“The Copenhagen Summit, A Climate Group Assessment”, January 2010http://www.theclimategroup.org/_assets/files/TCG-Copenhagen-Assessment-Report-Jan10.pdf“Less smoke, less fire”, The Economist.com. 23.09.2010

225 STC 10 E bis

9

Developing countries: the African Group and the Alliance of Small Island States

45. The results of the Copenhagen Summit were perhaps the most disappointing for the AfricanGroup, comprised of 50 countries, and the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), a coalition of43 small islands and low-lying coastal countries which are most affected by the rising sea levels.Most of these countries were hoping for higher emission reductions, so as to restrict the globaltemperature rise to 1.5�C. Nonetheless, as was already expected even prior to the onset of theSummit, all references to 1.5�C were removed at the last minute, as were the references to a1680% global emission reduction by 2050.

IV.

THE POST-COPENHAGEN STRATEGY: PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT ANDRECOMMENDATIONS

46. In the wake of the Copenhagen Summit, several follow-up meetings took place inpreparation for the next high-level annual meeting in Cancun, Mexico in late November 2010. Thepublic pressure on policymakers to achieve tangible progress at the Mexico meeting will haveincreased due to unusually high temperatures during the summer of 2010. Russia in particularsuffered from unbearable heat and horrific wildfires. The disastrous oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico,although completely unrelated to climate change, also increases general public support forenvironmentalist policies.47. However, the prognosis of most politicians, environmentalists and experts from the scientificcommunity, is that the conclusion of an international and legally binding climate treaty in 2010 ishighly unlikely. Yet, at the same time, there is general disagreement in the expert community as towhether a legally binding treaty is indeed indispensable, or whether national actions, in a form ofpolitically binding commitments, represent a more practical and feasible way forward.48. The reality is that the list of problems related to climate talks is so extensive that the chancesof establishing a legally binding treaty are almost nil. Even Christiana Figueres, the currentExecutive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, admitted that “there isno magic bullet, no one climate agreement that will solve everything right now” and suggested17focusing on a step-by-step approach. The main obstacles are related to President Obama’sdomestic political problems, to China’s unwillingness to compromise, to the lack of internationalleadership on this issue, and to the paralysis of UN institutions when it comes to negotiating andimplementing any agreement.49. It is widely agreed and insisted upon by many countries that the world’s biggest emitters –China and the United States – must endorse real emission cuts. However, both the United Statesand China have very fixed positions that are unlikely to change in the run-up to the upcoming talksin Mexico. Currently, China has already undertaken important steps to reduce the increase ingreenhouse gas emissions and to develop clean technologies. Despite pushing forward withambitious national strategies, China is not too keen to be tied to a legally binding agreement. Thisis because most developing countries believe that rich countries took far less than their share ofthe responsibility and have demonstrated rather poor performance in meeting the Kyoto-settargets of carbon reduction. Politically, adherence to a legally binding agreement is seen by somein China and other developing nations as equivalent to being patronised by the Western powers.

16

17

“Copenhagen closes with weak deal that poor threaten to reject”, John Vidal and Jonathan Watts.The Guardian.19 December 2009.http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2009/dec/19/copenhagen-closes-weak-deal“Key UN climate talks open in China”, BBC News online 4 October 2010.

225 STC 10 E bis

10

50. The United States, on the other hand, owing to numerous domestic reforms undertakenrecently, will hardly be in a position to assume a leadership role at the Mexico Summit. PresidentObama’s Administration is very unlikely to push for radical climate change reforms, as there is littlepolitical will to repeat the dramas associated with implementing domestic healthcare reforms.Additionally, the loss of the pro-presidential qualified majority in the Senate significantly slimsdown chances of a climate bill being passed. Therefore, the milestone bill adopted in 2009 by theHouse of Representatives had to be revised to increase the chances for it to be endorsed by theSenate. The new version of the bill contains no reference to carbon cap-and-trade system andessentially offers little more than some subsidies for certain energy efficiency and low-carbontechnologies. About two-thirds of American voters identified as “conservatives” are sceptical aboutclimate change so the possible victory of conservative candidates at the November 2010 electionsis likely to further reduces prospects of adoption of President Obama’s climate bill. That said, theUS administration has other tools at its disposal to enforce emission reductions, for instance byapplying the Clean Air Act against the largest emitters and by imposing more rigorous fuel andenergy efficiency standards. Various US states have introduced emission reduction strategies orare planning to do so. However, without a proper federal law, administrative or state-levelmeasures are unlikely to help the US achieve the 17% reduction pledge (experts of the World18Resources Institute assess that these measures can at best result in 13% reduction by 2020).51. It is indispensable that the United States be in favour of reducing its carbon emissions, butthis is not the only prerequisite for success. If domestic political considerations prevent the UnitedStates from pushing for an ambitious post-Kyoto agreement, the EU must step in to fill theleadership vacuum. The role of the EU is critically important to avoiding developingcountries’ disillusionment with “the West” and to preserving the latter’s support for a UN-ledclimate change effort. The European Commission has officially proposed unilaterally increasingthe emission reduction target to 30%, up from 20%, by 2020 compared with 1990 benchmark. Ifadopted, this proposal would reinforce Europe’s claim for leadership in climate negotiations, butthe cost of this action might be unacceptable to many European nations. According to theEuropean Commission’s assessment, reaching the 30% target would require €81 billion,compared with €48billion in the case of the 20% target. The French and German governmentshave already expressed their opposition to the proposal, which, they argue, would significantlyharm European industry and increase energy prices for the people. Thus, the prospect of the EUregaining the status of a leading player in climate negotiations can hardly be achieved withoutstrong political will and determination by the European policymakers.52. The paralysis of the UN is another serious obstacle to successful climate changenegotiations. The UN as an institution is a great forum for an exchange of opinions, but, at thesame time, reaching a consensus on a legally binding treaty among 190 countries is impossibleand a tantalising task. The UN is the main vehicle for climate negotiations as it is the onlyinstitution which can address global problems, such as climate change. Also, many major pollutingcountries insist that negotiations are conducted via the UN, as they believe that this forum best19protects their national interests.53. The UN as a venue for negotiation, nonetheless, needs to be responsive and address allpossible concerns that countries might have, as well as to ensure a fair and transparent process.This, in turn, makes effective negotiations impossible, especially when most countries areunprepared for compromise. The Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate (MEF) and theG20, have both been proposed as possible alternative venues for climate change negotiations.20Both include the world’s major emitters. However, the dangers of changing the negotiation venue1819

20

“Let It Be”,The Economist,29 July 2010.“A Post-Copenhagen Pathway”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Sarah O. Ladislaw.11 January 2010.http://csis.forumone.com/files/publication/100111_Ladislaw_Post_copenhagen.pdfIbid.

225 STC 10 E bis

11

is that the climate deal will only be negotiated by the biggest emitters and will effectively excludethe most affected countries, like the small islands, from the negotiation process. In other words, adeal struck only among emitters would render over 100 countries voiceless, and would furtherreduce the chances of setting the global temperature rise to 1.5�C as opposed to the current212�C.54. As the goal of concluding a UN-brokered and legally binding climate treaty appears to beunfeasible, some experts are now championing the idea of reaching at least a “politically binding”agreement that will commit countries to individual action through domestic policies. Some suggestthat focusing on issues at hand will allow issues to be addressed immediately. Instead of settinglong-term targets, the focus should be on near-term targets that are pragmatic and technology-22based. For instance, a multinational initiative could be launched to address one of thecontributors to global warming, the ‘black carbon’, the pollution resulting from burning solid as wellas diesel fuel and biomass, mostly in household cooking.55. Reversing deforestation is also seen as a relatively inexpensive and effective way to mitigateclimate change. It is estimated that deforestation is responsible for 17% of global anthropogenicgreenhouse gas emissions. The problem of deforestation is essentially limited to tropical regionsas the cover of boreal and temperate forests remains stable. Tropical deforestation is usuallycaused by extensions of farmlands, commercial logging and other human activities. Sometechnical fixes are not particularly challenging. For instance, sharing best practices of the woodindustry could ensure that logging does not result in increase of emissions: it is essential that allwood is converted into products rather than left to decompose (which would release carbon).Reforestation is also regarded as an important means of climate change mitigation, but one has tobear in mind that forests planted by humans, particularly in the tropical regions, are less effectivethan mature and intact forests in terms of carbon storage. In order to encourage sustainableforestry, tools such as forest carbon markets and credits as well as direct international assistanceshould be further promoted. However, as most of the tropical forests grow in developing countries,actual enforcement of sustainable forestry policies might be a serious issue as monitoring and23measuring forests is a significant challenge.56. In addition to these focused programmes, many experts argue that although a bindingagreement can help boost confidence among participant countries, addressing the major prioritiesare not necessarily contingent upon a globally binding agreement, but can equally be addressedvia multilateral co-ordination. Reduction of emissions, development of a global carbon market,promotion of energy savings and efficiency, preparation of adaptation plans and capabilities are24goals that can even be addressed by well co-ordinated multilateral co-operation.57. It is also suggested that even without any universal agreement, there is an increasingnumber of nations choosing to invest more in green technologies. These investments increased by230% from 2005 to 2009 (due to the global credit crunch, investments declined rather25insignificantly in 2009). According to the International Energy Agency’s 2009 World Energy21

22

23

24

25

“Experts on the chances of a global climate deal working in Mexico in 2010”, The Guardian.1 February 2010.http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2010/feb/01/experts-chances-global-climate-deal“The road from Copenhagen: the experts' views”,Nature Reports Climate Change.28 January 2010.http://www.nature.com/climate/2010/1002/full/climate.2010.09.html“Deforestation and Climate Change”, By Ross W. Gorte and Parvaze A. Sheikh. CongressionalResearch Service report. 24 March 2010.“A Post-Copenhagen Pathway”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Sarah O. Ladislaw.11 January 2010.http://csis.forumone.com/files/publication/100111_Ladislaw_Post_copenhagen.pdfWho’sWinningtheCleanEnergyRace?G-20CleanEnergyFactbook,http://www.pewtrusts.org/uploadedFiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/Reports/Global_warming/G-20%20Report.pdf

225 STC 10 E bis

12

Outlook, investments in clean energy sector surpassed those in the oil and gas industry. The G20accounts for 90% of the investments, and as of 2009 China has taken over as leading power inthis regard, surpassing in absolute numbers, the United States, Britain and other Westerncountries. The Danish government has announced that it is working on a roadmap designed tomake Denmark completely fossil-fuel-free by 2050.58. That said, it is plausible that all these concrete developments are an indirect result of risingglobal climate change awareness and discussions on a universal action on climate change. TheRapporteur is convinced that it is too early to give up on hopes of a universal climate pact.Dual-track strategy must be followed, emphasising both a “step-by-step” approach and the needfor a new but more ambitious Kyoto. Relying merely on national action plans is unlikely to helpreach the global 2�C target. Even if national pledges presented before the February 2010 deadlinewere to have been translated into legislation and actually implemented – a big “if” –, the worldeconomy would still be pumping enough CO2into the atmosphere to make our planet roughly 3�Cwarmer than pre-industrial levels. The top-down approach is indispensable, if we are to avoiddreadful consequences of climate change. It is important to keep this objective on the agendabecause the mere process of negotiations is valuable in itself. It could help to achieve at leastsome tangible progress: for instance, the upcoming high-level meeting in Mexico might not reachan agreement on a global climate pact but it is reasonable to expect decisions clarifying thefunctioning of specific mechanisms dealing with financial support, technology transfer, nationalprogress verification, and deforestation.59. In addition, there is a need to reinvigorate the scientific debate in order to address the re-emergence of doubts in our societies regarding the anthropogenic origins of global warming.Indeed, the mainstream science might have been too dismissive of its opponents. Even if theIPCC general findings remain valid and unquestionable, the sceptical researchers, who are in theminority, ought nevertheless be given more opportunities to present their arguments. Only anhonest and open-minded scientific debate can help alleviate existing uncertainties in society. Thestructure of IPCC needs to be reformed to make it more transparent, inclusive and trustworthy.60. The NATO Parliamentary Assembly should continue to serve as a forum for climate changedebate among legislators of the Euro-Atlantic region, contributing to the mobilisation of publicsupport and political will for concerted international action on climate change. In the run-up to theLisbon Summit, the Rapporteur wishes to reiterate the Science and Technology Committee’sposition that implications of global climate change deserve more concerted attention within theAlliance and should feature in the new Strategic Concept as one of the crucial factors shaping thecurrent and future security landscape. The Rapporteur supports the recommendation made by theGroup of Experts on a New Strategic Concept for NATO that the Alliance could “be called upon tohelp cope with security challenges stemming from such consequences of climate change as amelting polar ice cap or an increase in catastrophic storms and other natural disasters. TheAlliance should keep this possibility in mind when preparing for future contingencies.”

________________