Sundheds- og Forebyggelsesudvalget 2013-14

SUU Alm.del Bilag 263

Offentligt

THE STATE DECIDESWHO I AMLACK OF LEGAL GENDER RECOGNITIONFOR TRANSGENDER PEOPLE IN EUROPE

Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters,members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaignto end grave abuses of human rights.Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universaldeclaration of human rights and other international human rights standards.We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest orreligion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

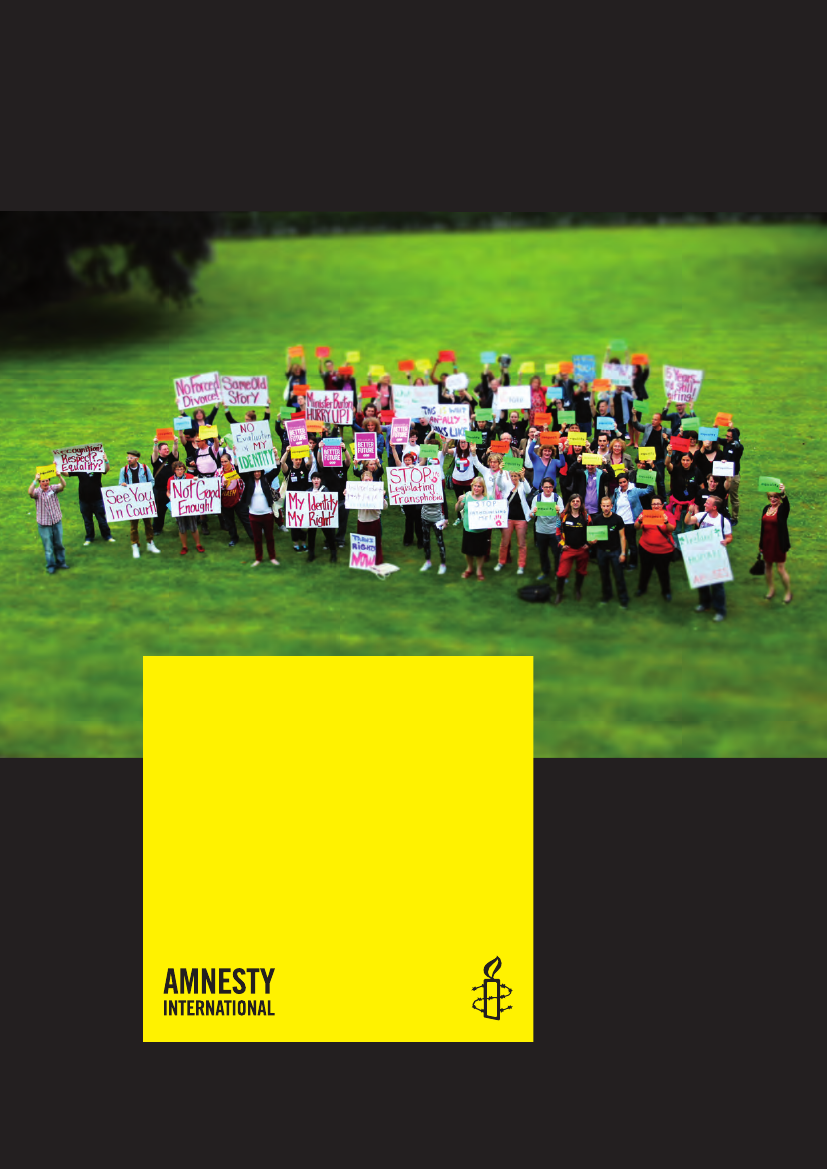

First published in 2014 byAmnesty International LtdPeter Benenson House1 Easton StreetLondon WC1X 0DWUnited Kingdom� Amnesty International 2014Index: EUR 01/001/2014 EnglishOriginal language: EnglishPrinted by Amnesty International,International Secretariat, United KingdomAll rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but maybe reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy,campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale.The copyright holders request that all such use be registeredwith them for impact assessment purposes. For copying inany other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications,or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission mustbe obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable.To request permission, or for any other inquiries, pleasecontact [email protected]Cover photo: The Rally for Recognition was organised by TEA(Trans* Education and Advocacy) at DCU, Dublin, September 2012.� Alison McDonnell

amnesty.org

CONTENTSCONTENTS ..................................................................................................................3INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................6A. What are gender identity and expression? .................................................................9B. How many transgender people live in Europe? ........................................................11C. Discrimination against transgender people because of their gender identity ...............11D. Aims and methodology .........................................................................................15E. Terminology ........................................................................................................161. LEGAL GENDER RECOGNITION AND HUMAN RIGHTS ..............................................181.1 The rights to private life and to recognition before the law ......................................201.2 The right to the highest attainable standard of health and to be free from cruel,inhuman and degrading treatment .............................................................................211.3 The right to marry and to found a family and the right to family life ........................261.4 The best interest of the child ..............................................................................271.5 Intersex people ..................................................................................................282. LEGAL GENDER RECOGNITION IN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES .....................................302.1 Denmark ...........................................................................................................302.1.1 Current laws and practices ...........................................................................312.1.2 Medical requirements: the psychiatric diagnosis .............................................322.1.3 Hormone treatments and surgeries ................................................................342.1.4 Sterilization ................................................................................................362.1.5 Consequences of current law and practices ....................................................372.1.6 Opportunities for changing laws and practices ................................................392.2 Finland .............................................................................................................40

2.2.1. Current policies and practices ..................................................................... 402.2.2. Medical requirements: the psychiatric diagnosis ............................................ 412.2.3 Other medical requirements: hormone treatment and sterilization .................... 432.2.4 Other requirements: change in marital status ................................................. 442.2.5 Consequences of current law and practices .................................................... 452.2.6 Opportunities for change.............................................................................. 472.3 France ............................................................................................................. 492.3.1. Case law ................................................................................................... 492.3.2 Current practices and requirements .............................................................. 502.3.3 Consequences of the current practices .......................................................... 532.3.4 Opportunities for changing laws and practices ................................................ 562.4 Ireland ............................................................................................................. 582.4.1. Case law and practices ............................................................................... 582.4.2 Consequences of legislative gaps and current practices ................................... 602.4.3 Opportunities for changing laws and practice ................................................. 642.4.4 The General Scheme of the Gender Recognition Bill 2013 .............................. 652.5. Norway ............................................................................................................ 702.5.1 Current laws and practices ........................................................................... 702.5.2 Medical requirements: the psychiatric diagnosis ............................................. 712.5.3 Other medical requirements: hormone treatment and surgeries ........................ 732.5.4 The sterilization requirement ........................................................................ 752.5.5 Consequences of current practices ................................................................ 762.5.6 Opportunities for changing laws and practices ................................................ 772.6 Other Countries ................................................................................................. 79

2.6.1 Belgium .....................................................................................................792.6.1.1 Current law and practices ..........................................................................792.6.1.2 Consequences of current practices and discrimination ..................................812.6.1.3 Opportunities for changing laws and practices .............................................822.6.2 Germany ........................................................................................................832.6.2.1 Current laws and practices ........................................................................842.6.2.2 Change of name: the minor solution ...........................................................852.6.2.3 Change of legal gender: the major solution ..................................................862.6.2.4 Opportunities for changing laws and practices .............................................893. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ..............................................................90APPENDIX I: HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARDS .................................................................95APPENDIX II: International Classification of Diseases, 10thVersion (ICD-10) ..................100

6

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

INTRODUCTION“Legal gender recognition is important as it is avalidation of who I am. When you are born you getyour birth certificate and when you die you getyour death certificate. People take that forgranted. It follows you all through life. Nobodythinks about it. But if I go into a social welfareoffice and someone wants to make my life difficult[because I don’t have documents reflecting mygender identity], I have no legal rights to relyon… Legal gender recognition also validates youwithin the rest of the population. If you are seento be legally recognized then you have morelegitimacy within the wider community, within thenon-transgender community, and that’simportant.”Louise, a transgender woman living in Dublin, Ireland

For transgender people, official identity documents reflecting their gender identity are vitallyimportant for the enjoyment of their human rights. They are not only crucial when travellingbut also for everyday life; depending on the specific country, individuals may be asked toproduce an official document when they enrol in school, apply for a job, access a publiclibrary or open a bank account.

Amnesty International January 2014

Index: EUR O1/001/2014

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

7

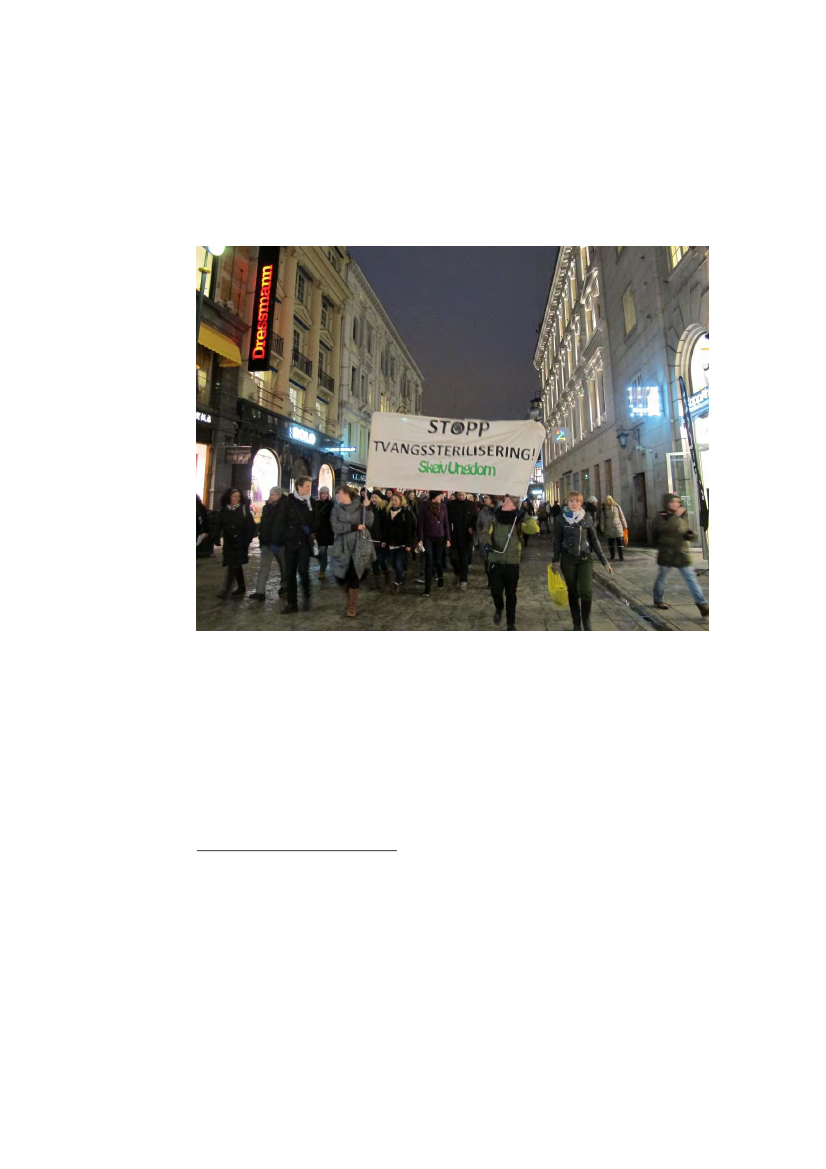

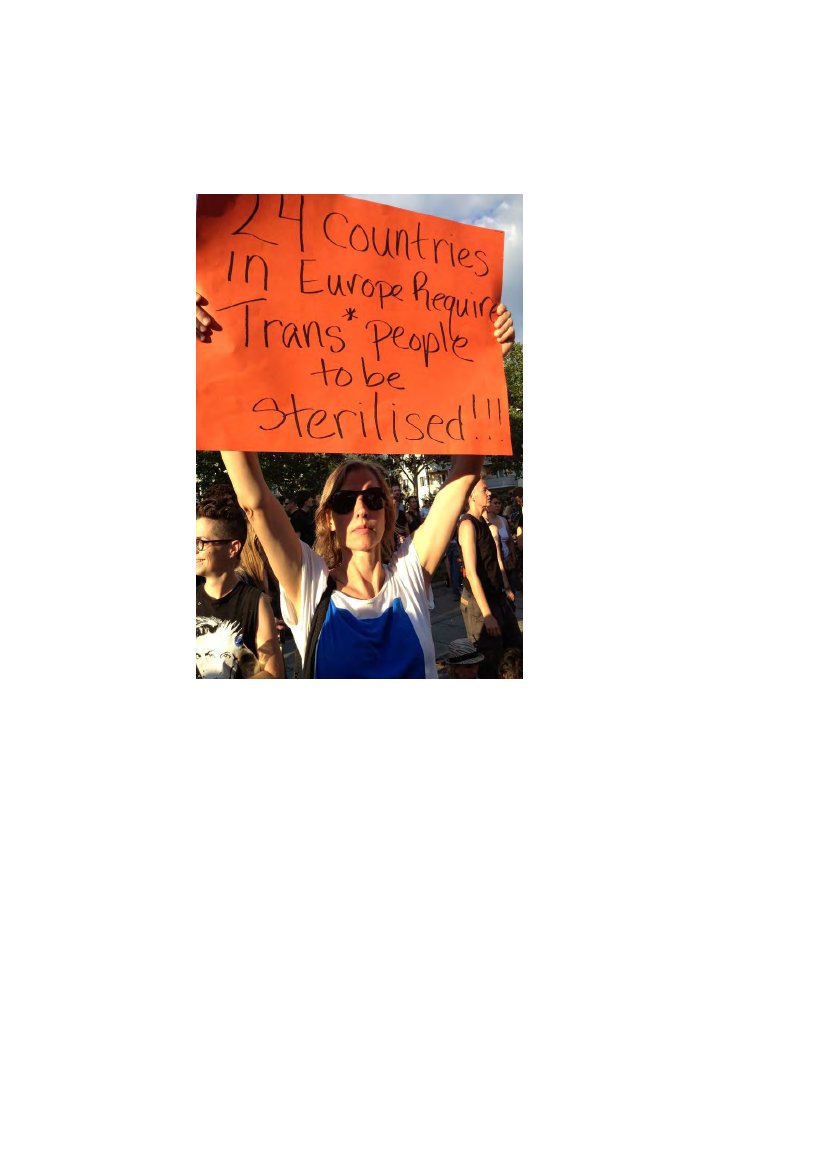

In 1992, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) first recognized that a state’s refusalto allow transgender people to change the gender markers on their official documents was aviolation of the European Convention on Human Rights.1More than 20 years later, however,many transgender people in Europe continue to struggle to have their gender legallyrecognized.Many states made the change in one’s legal gender contingent on the fulfillment of invasiverequirements, which violate the human rights of transgender people, through procedures thatusually take years. In these instances, transgender people can obtain legal gender recognitiononly if they are diagnosed with a mental disorder, agree to undergo medical procedures suchas hormone treatments and surgeries, are single or of age. Some other countries simply donot allow for a change in one’s legal gender.In many countries, even those with a reputation for championing equality and human rightssuch as Belgium, Denmark and Norway, as well as about 20 other countries in Europe2,transgender people have to undergo surgeries to remove their reproductive organs, resultingin irreversible sterilization. If they decide not to undergo such surgeries, they must continueto bear documents indicating the gender on the basis of the sex they were assigned at birth –even if that contradicts their appearance and identity.In fact, transgender people face an invidious situation in which they have to choose somehuman rights at the expense of others. Enjoying all of their human rights is not an optionavailable to them. The choices are stark. Obtain documents reflecting their gender, whichwould ensure their right to private life, or refuse to divorce their partners? Beingacknowledged by the state and enjoying equal recognition before the law, or preserving theirreproductive rights by refusing to undergo sterilization? Forcing such choices on transgenderpeople is contrary to the states’ obligations to ensure that everyone can enjoy human rightswithout discrimination, including on grounds of gender identity and expression.Transgender people should be able to obtain legal gender recognition through quick,accessible and transparent procedures and in accordance with their own perceptions ofgender identity. States must ensure that transgender people can obtain documents reflectingtheir gender identity without being required to satisfy criteria that in themselves violate their

1 European Court of Human Rights, Case of B. v France, no. 13343/87, 1992.2 According to the Transgender Europe’s Trans Rights Map Index published in May 2013, 24 countries in Europe required transgender people to be sterilized in orderto obtain legal recognition of their gender. On 17 December 2013, the Dutch Senate (Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal) adopted a bill that had already been adoptedby the House of Representatives (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal). The law proposal amends Article 28 of the Civil Code which, since 1985, allows transgenderpeople to obtain legal gender recognition provided that they have adapted their bodies’ appearance through hormone treatments and surgeries insofar as it was possibleand safe and that they are permanently and irreversibly infertile. The new law will enter into force on 1 July 2014. It provides the possibility for transgender people whoare aged 16 and above to obtain legal gender recognition legal gender recognition by introducing a declaration to the civil registry supported by an expert’s certificate.EK 33. 351, article I/B https://www.eerstekamer.nl/wetsvoorstel/33351_wijziging_vermelding_van, in Dutch, accessed 2 January 2014. In June 2013, Croatia adoptedthe Law on Amendments on the Law on State Registers (No.71 -05-03/1-13-2). According to Article 9A, medical evidence from treating physicians or other healthfacilities is needed for the purposes of legal gender recognition. The Ministry of Health is charged with developing guidelines on the legal gender recognition procedurethat should also specify what medical evidence is needed (Article 36). In January 2014, such guidelines had not been developed yet. According to Article 37, previousguidelines adopted in 2008 remain in force (26/08).

Index: EUR 01/001/24

Amnesty International January 2014

8

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

human rights. For that purpose, legal gender recognition should not be made contingent onpsychiatric diagnosis, medical treatments, single status or blanket age requirements.

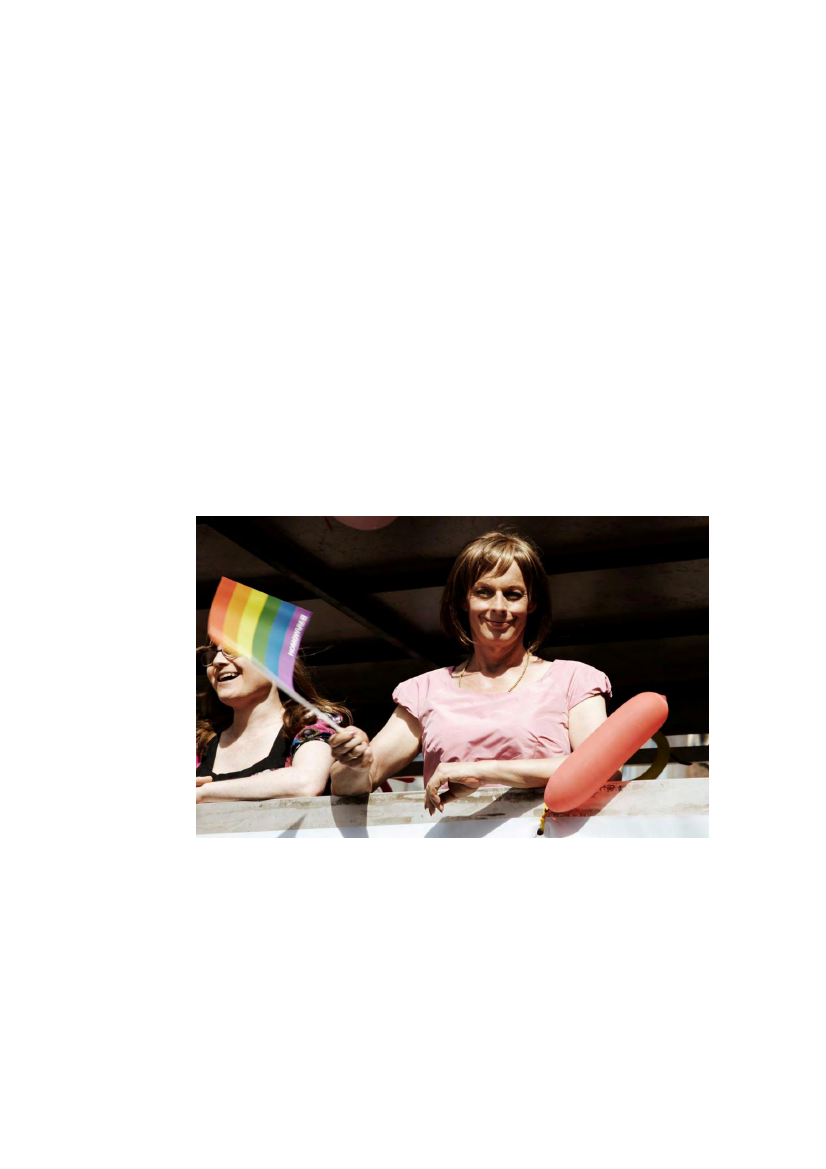

Demonstration for gender legal recognition outside Leinster House in Dublin October, 2012 � Sasko Lazarov /Photocall

Amnesty International January 2014

Index: EUR O1/001/2014

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

9

A. WHAT ARE GENDER IDENTITY AND EXPRESSION?“It is so difficult to live a life where you feel a constant discrepancy between what you are and how others perceive you.”Hélène,Paris, France

In all societies, gender norms determine what is deemed “appropriate” behavior for men andwomen, which may include dress, speech and mannerisms. These gender norms are nothomogenous across societies; they differ from place to place and across time. But individualswho transgress these boundaries – whose behavior lies outside of the accepted gender norms– often face stigma and discrimination, harassment, and sometimes even violence andmurder.In most countries, individuals have a legal gender that corresponds to the sex they wereassigned at birth. This appears on multiple official documents (including birth certificates,identity cards and passports) and determines how they are perceived throughout their lives.Those whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth or those whowish to express their identity in ways that are considered at odds with gender norms mustchoose between suppressing their own sense of self, or publicly transgressing genderboundaries and bearing all the potential negative consequences.People generally do not experience and perceive their gender identities according to onestandardized pattern. Transgender people, whose innate sense of their own gender differsfrom the sex they were assigned at birth, also experience and express their gender identityaccording to a variety of patterns. Their perceptions of gender identity may also evolve overtime. Some transgender people identify themselves as fully male or female; others perceivetheir gender identity in a continuum between the two. According to a survey undertaken inBelgium, only 55 per cent of those transgender people who were assigned the male sex atbirth identified themselves as either fully or mainly female. Similarly, only 60 per cent ofthose transgender people who were assigned the female sex perceived themselves as eitherfully or mainly male. The rest identified as neither male nor female, both male and female, or“other”.3While some transgender people are willing to undergo all available health treatments,including surgeries aimed at modifying their bodies according to their gender identity, othersprefer to access only some procedures, and in some cases, treatments are not sought at all.Throughout the research for this report, Amnesty International spoke to transgender peoplewhose gender identities greatly vary. Joshua was assigned the female sex at birth butperceives himself as a man: “I’veseen myself as a male since I was four. I did not even knowI was born female until my cousin peed in front of me and I could see the difference in ourbodies. My gender identity was firmly established at that point and has not changed overtime.”4

3 Joz Motmans, Being transgender in Belgium. Mapping social and legal situation of transgender people, 2010, p. 100, http://igvm-iefh.belgium.be/fr/binaries/34%20-%20Transgender_ENG_tcm337-99783.pdf, accessed 6 December 2013.4 Interview with Joshua, Copenhagen, 22 October 2013.

Index: EUR 01/001/24

Amnesty International January 2014

10

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

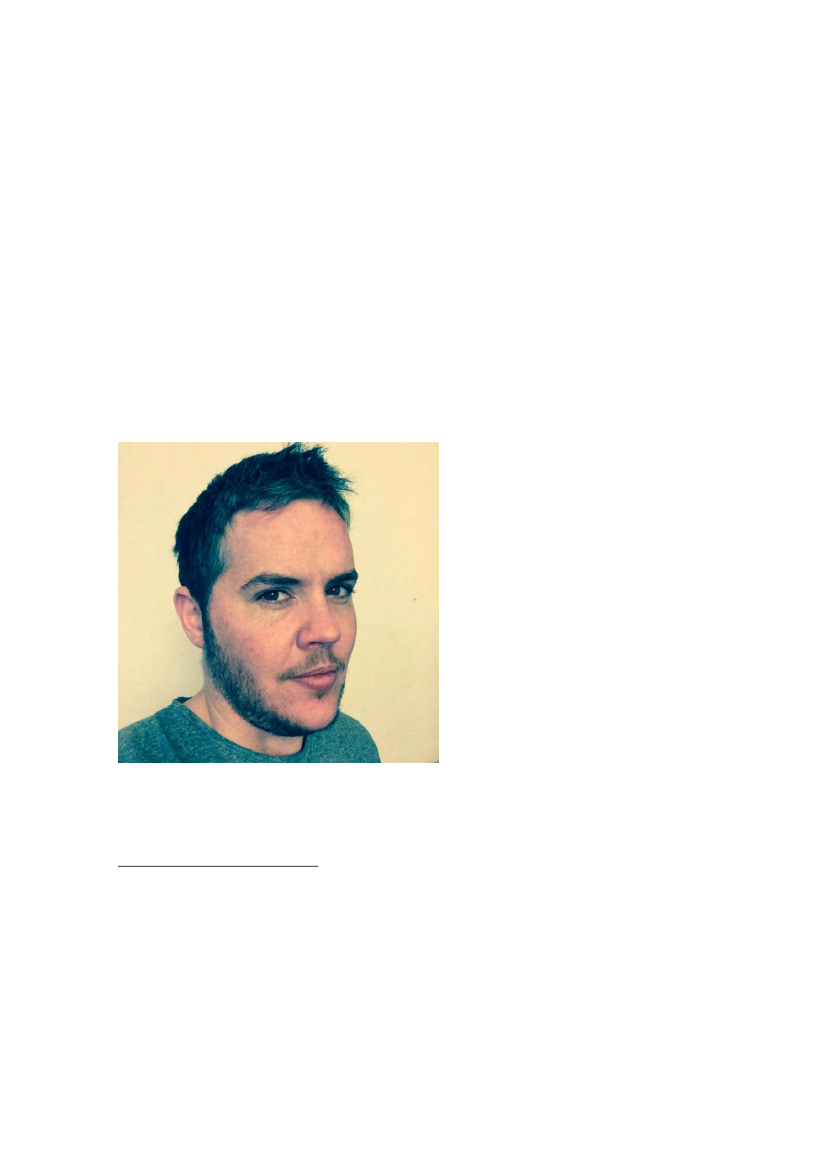

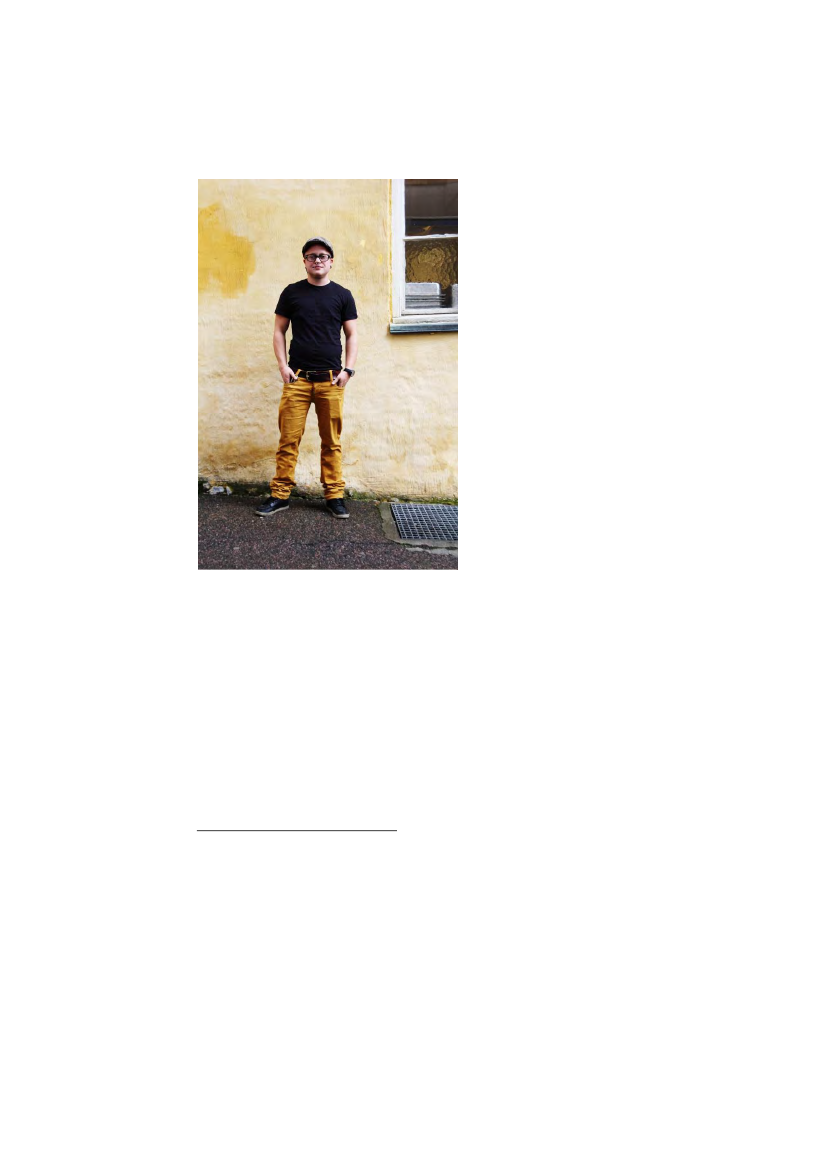

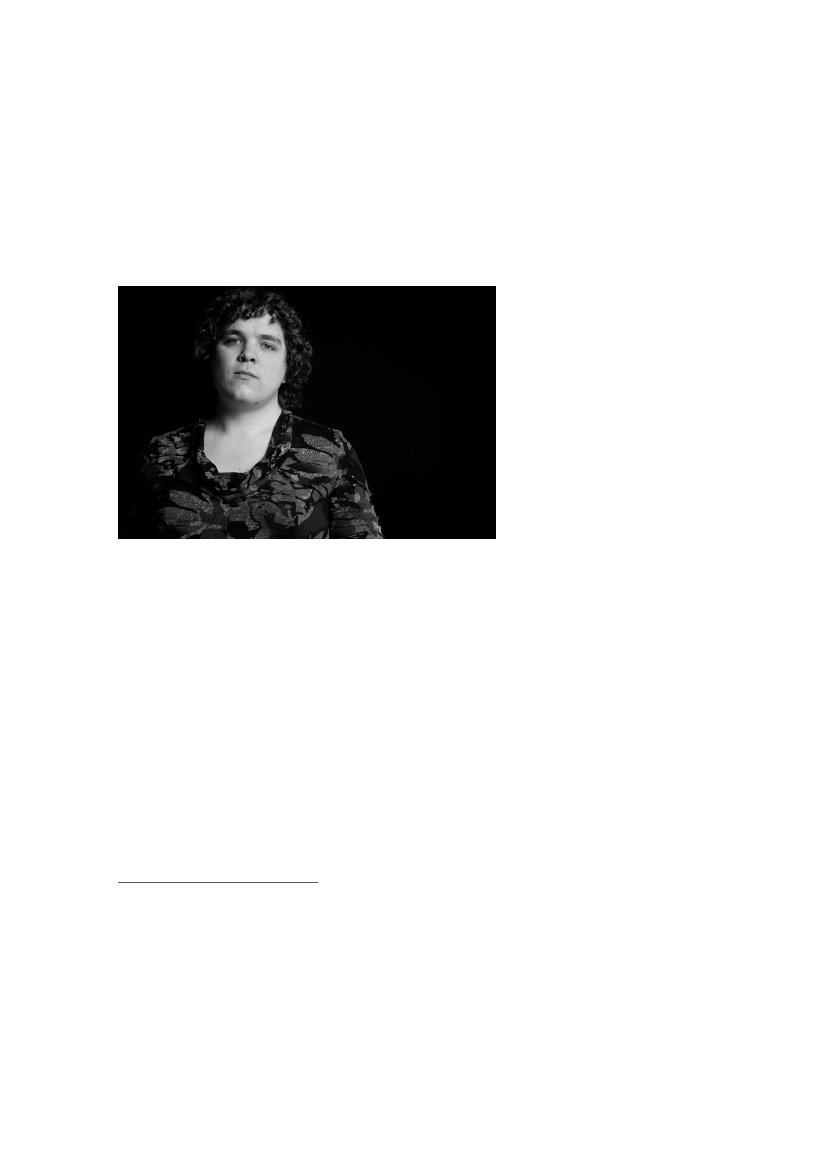

Bjørk was assigned the male sex at birth:“It’s a bit tricky when it comes to my genderidentity. Intellectually I think a third gender would fit me the best. I don’t think I belong toeither the male or the female gender. It’s the same with my sexual orientation. I considermyself as bisexual. I haven’t been happy with my male body since the age of four. My familywas transphobic and homophobic. I wanted to come out as a trans person but I alwaysthought about the reactions of those who surrounded me.”5N. was assigned the male sex and sees herself as a woman:“I am a woman with a transbackground. I perceive myself as a woman who has a little bit of a different history than otherwomen usually do. When I was a child, I wondered about my anatomy. I felt puzzled. When Iwas with boys, I felt like I was in a foreign country. I learned to speak the language but I feltI was not originally from there. I was 26 when I fully realized that I was transgender.”6Luca was assigned the female sex: “Idon’tperceive myself at either one end or the other ofthe spectrum; I wander somewhere between, oroutside. The society and our culture alwaysplace people in two categories, so one needs tonegotiate [how to position oneself] in differentsituations. I am a masculine trans. The way Iperceived my gender identity has always beenthe same but the way I describe it has changedover time.”7Runar Randi Beate is a man who often wearsfemale clothes and makeup. “I’maheterosexual man, and I’m quite pleased withthat. The feminine side is a part of me and ithas to get out in order for me to feel I am acomplete human being. I have to live out thatpart as well, to a greater or lesser extent. Itcomes and goes. It depends. The dressing styleon the other hand has changed; it is now morefashion-oriented and classy”.8Randi Beate from Norway, a man who sometimes needs toexpress his feminine side � Amnesty International

5 Interview with Bjørk, Copenhagen, 23 October 2013.6 Interview with N, Helsinki, 16 July 2013.7 Interview with Luca, Helsinki, 5 July 2013.8 Interview with Runar, Oslo, 23 June 2013.

Amnesty International January 2014

Index: EUR O1/001/2014

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

11

Hélène was assigned the male sex at birth: “Iam a transsexual. I know that it may makepeople uncomfortable and that there are not many people who define themselves astranssexuals. I want to undergo genital reassignment surgery, which is important for me inorder to live as a woman. I couldn’t do that with male genital organs. I have felt I am afemale since the age of four or five but it took me many years to come out… I was 48.”9

B. HOW MANY TRANSGENDER PEOPLE LIVE IN EUROPE?The exact number of transgender people living in Europe is unknown. Social scientists havedeveloped various estimates on the prevalence of transgender people in the generalpopulation that stir lively debates, especially because they reach very divergent conclusions.In the past, estimations were primarily based on the number of people who had undergonegenital reassignment surgeries or were undergoing hormone treatment, using data sourcedfrom health professionals. Other estimations were based on the number of people whoobtained legal gender recognition. According to some of these estimates, there may bearound 30,000 transgender people in the European Union.10However, those estimates fail to take into account all transgender people who do not undergoreassignment surgeries or other health treatments. More recent estimates have been basednot only on health related data but also, in some instances, on gender identity relatedquestions undertaken in the context of survey research. Such surveys suggest there could beas many as 1.5 million people in the EU who do not fully identify with the sex they wereassigned at birth.11

C. DISCRIMINATION AGAINST TRANSGENDER PEOPLE BECAUSE OF THEIR GENDERIDENTITYWhether at school or in the workplace, transgender people are often discriminated against

9 Interview with Hélène (pseudonym), Paris, 28 June 2013.10 According to Eurostat, there were 505 million people living in the EU’s 28 member states as of 1 January 2013. There were 104,8 women per 100 men. Severalstudies on the prevalence of transsexualism have been carried out since the 1960s. Such studies however only refer to transsexual people, who constitute just a portionof transsexuals people. According to these estimations, the highest prevalence is 1:11.900 for male-to-female transsexuals and 1:30.400 for female-to-maletransgender. For a review of these estimations, see Femke Olyslager and Lynn Conway, “On the calculation of the prevalence of transsexualism”, 2007,http://ai.eecs.umich.edu/people/conway/TS/Prevalence/Reports/Prevalence%20of%20Transsexualism.pdf, accessed 9 December 2013. These are also the highestestimates indicated by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) in Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gendernon-conforming people, Version 7, p7, http://www.wpath.org/uploaded_files/140/files/Standards%20of%20Care,%20V7%20Full%20Book.pdf11 Gates indicated in 2011 that 0.3 per cent (1:333) of the US adult population may identify as transgender. If applied to an EU population of about 505 million, thatprevalence rate means that there may be approximately 1.5 million transgender people in the EU. Gary J. Gates, How many people are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual andTransgender? 2011, http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf;Reed indicated that the prevalence of transgender people who seek health treatments might be 0.02 per cent (20:100,000) in the UK. However, 0.6 per cent(600:100,000) of the population may experience some gender variance irrespective of whether health treatment is sought or not. Reed et al., Gender variance in theUK: prevalence, incidence, growth and geographical distribution, 2009, http://www.gires.org.uk/assets/Medpro-Assets/GenderVarianceUK-report.pdf;Femke Olyslager and Lynn Conway, On the calculation of the prevalence of transsexualism, 2007, indicated that the lower bound prevalence is 0.2 per cent (1:500) orhigher, http://ai.eecs.umich.edu/people/conway/TS/Prevalence/Reports/Prevalence%20of%20Transsexualism.pdf (all sources accessed on 5 December 2013).

Index: EUR 01/001/24

Amnesty International January 2014

12

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

because of widespread prejudices and gender-based stereotypes stemming from standardizednotions of masculinity and femininity.Such discrimination occurs irrespective of whether or not transgender people bear documentsthat reflect their gender identity. However, the lack of such documents can further exposetransgender people to discrimination whenever they have to produce a document with gendermarkers that do not correspond to their gender identity and expression. Such involuntary“outings” are a major concern in countries where transgender people cannot access legalgender recognition or where burdensome and lengthy procedures make it difficult to do so.In a European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) survey of lesbian, gay, bisexualand transgender people in Europe (hereafter referred to as FRA LGBT survey), 29 per cent ofthe transgender respondents said they had been discriminated against in the workplace orwhile looking for jobs in the year ahead of the survey.12Thirty-five per cent of them said theyhad experienced violence or the threat of violence during the five years ahead of the survey.Fifty per cent of those who had experienced violence or the threat of violence in the 12months ahead of the survey, perceived they had been victimized because of their genderidentity.13In recent years, dozens of transgender people have been killed in Europe – at least84 since January 2008, with the highest numbers in Turkey (34) and Italy (26).14Although few states in Europe collect disaggregated data on hate crime perpetrated ongrounds of gender identity, existing statistics raise concern. For example, more than 300hate crimes were perpetrated against transgender people in England and Wales in the UnitedKingdom in less than a year between 2011 and 2012.15In some instances, publicauthorities, including the police, harass transgender people. For example, in 2012 dozens oftransgender women in Greece were arrested and forced to undergo HIV tests. The arrests weremade on the basis of a regulation that had been introduced in May of that year, thensuspended in June 2013 and subsequently reintroduced in July.

12 European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, European Union lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender survey, results at a glance, 2013, pp. 21-22,http://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eu-lgbt-survey-results-at-a-glance_en.pdf, accessed 5 December 2013.13 European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, European Union lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender survey, results at a glance, 2013, pp. 21-22,http://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eu-lgbt-survey-results-at-a-glance_en.pdf, accessed 5 December 2013.14 Trans-Murder Monitoring Project, Transgender Europe, last data update 21 November 2013http://www.transrespect-transphobia.org/en_US/tvt-project/tmm-results.htm/tdor-2013, accessed 5 December 2013.15 The police recorded more than 43,000 hate crimes between April 2011 and March 2012. Hate crimes against transgender people include any criminal offence thatis perceived, by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by a hostility or prejudice against a person who is transgender, or perceived to be transgender,https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hate-crimes-england-and-wales-2011-to-2012--2/hate-crimes-england-and-wales-2011-to-2012, accessed 5 December2013. For individual cases of transphobic hate crimes and information on legislative gaps in Europe, see Because of who I am: homophobia, transphobia and hatecrimes in Europe (Index: EUR 01/014/2013).

Amnesty International January 2014

Index: EUR O1/001/2014

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

13

In May 2013, the police in the city of Thessaloniki arbitrarily stopped a number oftransgender women for identity checks and then arrested them for several hours.16

ANNA: DISCRIMINATED AGAINST AT SCHOOLAnna, a 26 year old transgender woman interviewed by Amnesty International, experienced discrimination andviolence in an evening school for secondary education in Athens, Greece. School authorities refused herpermission to express her gender identity. She told Amnesty International: “I went to the headmaster’s office inorder to enrol and he asked me if I was there to enrol my brother. I answered no and I told him my name wasAnna. His colleague interrupted us and told him my name was Panagiotis [Anna’s legal male name]. Theheadmaster told me that he had been informed about my situation and that he wouldn’t accept any gay ortrans in his school. He said I had to cut my hair, stop wearing make-up, wear men’s clothes and generally actas a male. He tried to alter my identity and suppress my rights… I was frightened and I accepted thoseconditions for a month… the worst month of my life. Other pupils made fun of me but when I told theheadmaster they were behaving like that because I was a trans person he replied that I was not trans becauseI hadn’t changed my gender. He said I was a gay man who wanted to show off in female clothes.”17Anna waseventually allowed to wear clothes that expressed her gender identity. Nevertheless, other pupils continued toharass and threatened her with violence and she felt school authorities did not take effective action to put anend to the situation.18In June 2012, Anna was victim of a serious attack when a pupil and his friend pouredgasoline on her and attempted to set her on fire just outside the school premises. Amnesty International wasalso informed by Anna’s lawyer that while a police car arrived at the scene of the incident, the attack was notsubsequently investigated.19Despite the intervention of the Greek Ombudsperson, Anna continued to face hostile and transphobicbehaviour by the school administration after she registered to the upper secondary school in September 2013.Anna also reported being subjected to verbal abuse and harassment by other pupils because of her genderidentity. In January 2014 Anna told Amnesty International that she felt forced to leave school because of theharassment she had experienced.

16 Greece must withdraw the provision on forced HIV testing and end harassment against transgender women, (Index; EUR 25/012/2013),http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/EUR25/012/2013/en/2d74d0f9-f321-4b55-a55f-44346ed3780c/eur250122013en.pdf17 Interview with Anna, 28 March 2013.18 In a letter to the Minister of Education and Religious Affairs dated 5 April 2013, Amnesty International raised concerns about the discrimination Anna experiencedat school. The letter sought further information on the measures taken by school authorities and other educational competent authorities to protect Anna from threats ofviolence and put an end to the discrimination she was experiencing. The Ministry replied on 10 July 2013 stating that the competent authority dealing with the officialcomplaint Anna filed against the headmaster concluded that he handled a complicated situation in the best way possible.19 Interview with Elektra Koutra, Anna’s lawyer, 15 January 2014.

Index: EUR 01/001/24

Amnesty International January 2014

14

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

L. CAVALIERO: SEXUALLY HARASSED BY HIS UNIVERSITYPROFESSORL. Cavaliero is legally a female but he identifies more as a male. He has a gender queer appearance and he isnot undergoing any health treatment to physically transition to the male gender. He was harassed andassaulted by a university professor in Berlin. He told Amnesty International: “WhenI started his course, Ipresented myself as a trans person to everyone and I said I preferred the masculine pronoun. Sometimes hemade fun of me, for example by referring to me as ‘this woman who wants to be a man’. At some point theother students started reacting because they were shocked by his behaviour, but he didn’t stop. I went to hisoffice to discuss the topic for the exam. He referred to me with the female pronoun, so once again I said Ipreferred the masculine one. He told me I was the first trans person he had ever met and that he had a lot ofquestions… At some point he asked me if I had male or female genitals… and he tried to grab in between mylegs. I told him he was not allowed to do that… He came towards me and then he started touching me. I wasagainst the wall. I screamed and then ran away.”20

LOUISE: DISCRIMINATED AGAINST IN THE WORKPLACELouise is a transgender woman living in Dublin, who used to work in the transport industry. In late 2006, sheinformed her employer that she intended to start her physical transition to her female gender. She was readyto resign as she thought that her transition would be problematic in that particular working environment.However, her managers appeared to be supportive and encouraged her to stay. Having decided to stay, sheaccessed hormone therapy, changed her legal name in March 2007 and started working as “Louise”. Problemsarose almost immediately. At the end of March, her managers told her she had to “go back to the male mode”for client meetings and she was banned from using the female toilets. Louise did not accept this position. “Istruggled to get to this point and I’m not moving back”she told Amnesty International. Her manager startedouting her in public; for example, he referred to her by her previous male name in front of clients. In early April,the manager said that the company had bought new premises and asked Louise to work from home for amonth because, as he put it, “there is an atmosphere in the office”. Louise worked from home from 24 April tothe end of July. She repeatedly asked to return to the office but was told there was no room. However, Louiseknew her desk was free up until the beginning of July. In the middle of July, the manager told her she was notproductive enough and suggested she looked for another job. She found another job in July 2007 but it fellthrough after a couple of weeks.21

20 Interview with L. Cavaliero, Berlin, 7 November 2012.21 Louise took her case to the Equality Tribunal, the body responsible for dealing with cases of discrimination. The Tribunal found that she was discriminated againston grounds of gender and disability, and that the request made by the employer to work from home was discriminatory. In July 2007, Louise asked to be reinstated inher previous job but her employer offered another position with unsociable hours and low pay instead, which she refused. The Equality Tribunal considered thistreatment as discriminatory. See Decision No. DEC-S2011-066, Hannon v First Direct Logistics Limited, 29 March 2011.

Amnesty International January 2014

Index: EUR O1/001/2014

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

15

D. AIMS AND METHODOLOGYThis report illustrates the human rights violations experienced by transgender peoplestemming from the requirements imposed on them to obtain legal recognition of their gender.In highlighting these requirements, including psychiatric diagnosis, medical procedures anddivorce, it underscores the plight of transgender people forced to choose which rights to giveup in order to enjoy others. The report shows the consequences of the current lengthy legalgender recognition procedures on the rights of transgender people, in particular the rights torecognition before the law, privacy and health, and to be free from discrimination and frominhuman and degrading treatment. This report does not focus specifically on the humanrights violations experienced by intersex people (see 1.5).Chapter 1introduces some common problematic aspects of procedures on legal genderrecognition in Europe and the human rights violations they entail. A summary of theapplicable international standards is included in Appendix I.Chapter 2provides an overview of existing legal gender recognition procedures in sevenEuropean countries: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland and Norway. Itincludes also succinct information on the current civil and criminal laws protecting againstdiscrimination and hate crimes on grounds of gender identity. Individual case studiesillustrate the impact of the current legal gender recognition procedures on the lives oftransgender people in Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland and Norway.Chapter 3draws conclusions and identifies both general and country specificrecommendations.The countries covered in this report were identified on the basis of two main criteria: a) thepresence of compulsory requirements for legal gender recognition that violate the humanrights of transgender people; and, b) the presence of opportunities for amending currentlaws, policies and practices, and a context to which Amnesty International could bring anadded value to achieving such change.The information included in this report was collected by desk research undertaken fromAugust 2012 to December 2013, and from research undertaken by Amnesty Internationalsections in Belgium, Denmark, Finland and Norway and a number of field-research missions.These include short 3-day missions to Finland (November 2012) and Germany (November2012), and longer 6-day missions to Norway (June 2013), France (July 2013) and Ireland(October 2013). Information was also collected in the context of Amnesty International’sparticipation in international conferences and seminars and in the framework of AmnestyInternational’s ongoing work on homophobic and transphobic hate crimes. In-depth researchwas undertaken in Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland and Norway, where individual casestudies have been researched and meetings held and contacts maintained with authorities.Research undertaken in Belgium and Germany was more limited in scope and aimedprimarily at reviewing the main laws and practices applicable to legal gender recognition.In the context of the research for this report Amnesty International interviewed about 70transgender individuals, 15 health and legal experts and representatives of more than 25transgender organizations in the countries covered. Interviews with transgender individuals

Index: EUR 01/001/24

Amnesty International January 2014

16

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

were undertaken in English, Danish, Finnish, French and Norwegian, without interpretation.Most of them were transcribed and translated into English when applicable. The quotes fromthe interviews reported here were lightly edited for brevity and clarity only. Interviewees areidentified in accordance with their informed consent, sought by Amnesty Internationalresearchers in each interview. In referring to interviewees the report always uses theirpreferred description of their gender identity and their preferred pronoun.Amnesty International acknowledges the crucial support of Transgender Europe and theEuropean region of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association(ILGA-Europe) in the context of this research.

E. TERMINOLOGYCisgenderpeople are individuals whose gender expression and/or gender identity accords withconventional expectations based on the physical sex they were assigned at birth. In broadterms, “cisgender” is the opposite of “transgender”.Gender Identityis a very personal and subjective matter. It refers to each person’s deeply feltinternal and individual experience of gender, which may or may not correspond with the sexassigned at birth, including the personal sense of the body (which may involve, if freelychosen, modification of bodily appearance or function by medical, surgical or other means)and other expressions of gender, including dress, speech and mannerism.Gender expressionrefers to the means by which individuals express their gender identity.This may or may not include dress, make-up, speech, mannerisms and surgical or hormonaltreatment.Gender markeris a gendered designator that appears on an official document such as apassport or an identity card. It may be an explicit designation such as “male” or “female”, agendered title such like Mr or Ms, a professional title, a gendered pronoun, or a numericalcode which uses particular numbers for men and for women (for example, odd numbers andeven numbers).Gender queerrefers to gender identities other than “man” and “woman”, falling thus outsideof the gender binary.Gender reassignment treatmentrefers to a range of medical or non-medical treatments that atransgender person may wish to undergo. Treatments may include hormone therapy, sex orgender reassignment surgery including facial surgery, chest surgery, genital or gonad surgery,and can include sterilization. In some states, certain forms of gender reassignment treatmentmay be compulsory for legal gender recognition. Not all transgender people feel a need toundergo gender reassignment treatment.Genital reassignment surgeriesrefer to operations aimed at modifying genital characteristicsto accord with a person’s gender identity. In some countries these surgeries result inirreversible sterilization as they entail the removal of reproductive organs.

Amnesty International January 2014

Index: EUR O1/001/2014

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

17

Intersexindividuals possess genital, chromosomal or hormonal characteristics that do notcorrespond to the given standard for the “male” or “female” categories of the sexual orreproductive anatomy. Intersexuality may take different forms and cover a wide range ofconditions.Sexual Orientationrefers to each person’s capacity for profound emotional, affectionate andsexual attraction to, and intimate and sexual relations with, individuals of a different genderor the same gender or more than one gender.Transgender,ortrans,people are individuals whose gender expression and/or gender identitydiffers from conventional expectations based on the physical sex they were assigned at birth.A transgender woman is a woman who was assigned the “male’ sex at birth but has a femalegender identity; a transgender man is a man who was assigned the “female” sex at birth buthas a male gender identity. Not all transgender individuals identify as male or female;“transgender” is a term that includes members of third genders, as well as individuals whoidentify as more than one gender or no gender at all. Transgender individuals may or may notchoose to undergo some, or all, possible forms of gender reassignment treatment.Transsexualindividuals have a gender expression and/or gender identity that differs fromconventional expectations based on the physical sex they were assigned at birth and whowish to undergo, are in the process of undergoing or have undergone, gender reassignmenttreatment. Transsexualism is included in the WHO International Statistical Classification ofDiseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10thversion) as a mental and behaviouraldisorder (See Appendix II).Transvestite (cross-dresser)describes a person who regularly, but not constantly, wearsclothes mostly associated with a gender other than the gender they were assigned at birth.

Index: EUR 01/001/24

Amnesty International January 2014

18

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

1. LEGAL GENDER RECOGNITION ANDHUMAN RIGHTS“Legal gender recognition is important because,once and for all, I wouldn’t have to battle withpeople [for anything] I have a right [to], like socialwelfare. Having a legal gender recognitioncertificate would make these issues easier,instead of fighting every corner, which is what I’vehad to do. I want to be recognised as who I bloodywell am. It’s ridiculous that the state doesn’trecognize me as who I am.”Victoria, a transgender woman living in Dublin

Internationally protected human rights are applicable to gender identity as acknowledged bythe Yogyakarta Principles, which crystallize the current status of human rights law in relationto gender identity and sexual orientation. Developed in 2006 by lawyers, scholars, NGOactivists and other experts, these Principles have been referred to by several international andregional organizations, governments and other authorities in the context of human rightstreaties’ monitoring activities or when developing policies on equality and non-discrimination.22

22 Yogyakarta Principles on the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation and gender identity.http://www.yogyakartaprinciples.org/principles_en.htm (accessed 15 January 2014). For examples of the impact of the Principles and the references made to them byinternational organizations and governments, see: Ettelbrick,P.L., Trabucco Zerán, A., The impact of the Yogyakarta Principles on International Human Rights LawDevelopments, 2010, http://www.ypinaction.org/files/02/57/Yogyakarta_Principles_Impact_Tracking_Report.pdf, accessed 15 January 2014

Amnesty International January 2014

Index: EUR O1/001/2014

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

19

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. Human beings of all sexualorientations and gender identities are entitled to the full enjoyment of all human rights.”Principle 1, Yogyakarta PrinciplesCentral to the respect for the human rights of transgender people is the recognition of genderidentity as a prohibited ground of discrimination. This is highlighted by the United NationsCommittee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR): “Gender identity is recognizedas among the prohibited grounds of discrimination; for example, persons who aretransgender, transsexual or intersex often face serious human rights violations, such asharassment in schools or in the workplace.”23The United Nations Committee on theElimination of Discrimination against Women has stated: “The discrimination of womenbased on sex and gender is inextricably linked with other factors that affect women, such asrace, ethnicity, religion or belief, health, status, age, class, caste and sexual orientation andgender identity.”24Gender expression should equally be considered as a protected ground,included in open-ended lists of grounds of discrimination in human rights treaties such asthe International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, Articles 2 and 26) or theEuropean Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR,Article 14).States can pursue legitimate aims by collecting, recording and keeping demographicinformation on the population, provided they put in place safeguards to ensure confidentialityand respect for the right to privacy. This can and often does include collecting information ongender. Recording information on gender is for example important for public health purposesor for designing, implementing and evaluating policies for combating discrimination ongrounds of gender and gender-based violence.Consequently, many forms of official documents issued to individuals, such as passports, IDcards and driving licences, include a gender marker. This may be explicit, such as a fieldlabelled “sex” marked with an M or F signifying “male” or “female” respectively,25orimplicit, like a unique identifying number that includes an even digit for “male” and an odddigit for “female”.Transgender people who have not been issued official documents reflecting their genderidentity have to constantly disclose information on their gender identity, even when theyprefer it to remain confidential. As a result they may be questioned about their identities andare at risk of being suspected of fraud, harassed, discriminated against or even physicallyattacked.

23 UN CESCR, General Comment No. 20: Non-discrimination in Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 2009, para32.24 UN CEDAW, General Recommendation No. 28: The Core Obligations of States Parties under Article 2 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms ofDiscrimination against Women (CEDAW), 2010, para18.25 There are countries that sometimes issue documents with other markers. For example, Australia, Denmark and New Zealand issue passports with an X gender markerand India issues passports with an E, while Nepal issues ID cards with gender markers for “male”, “female” and “other”.

Index: EUR 01/001/24

Amnesty International January 2014

20

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

States must ensure that transgender people can obtain legal recognition of their gender –including issuing all documents with correct gender markers and changing the gender-relatedinformation kept in state-run registries – through a quick, accessible and transparentprocedure in accordance with the individual’s own sense of their gender identity, whilepreserving their right to privacy.

OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS, DISCRIMINATION AND EU LAWAs shown by the many cases included in this report, transgender people who do not have documents reflectingtheir gender identity and expression can be discriminated against in areas such as employment, educationand access to goods and services. Procedures aimed at allowing transgender people to obtain legalrecognition of their gender are therefore essential to ensure that they are not discriminated against.EU anti-discrimination law does not explicitly prohibit discrimination on grounds of gender identity andexpression. However, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union prohibits discrimination on anopen-ended list of grounds (Article 21). Gender identity and expression are not protected grounds in EUDirectives aimed at combating discrimination on grounds of sex, including Directive 2004/113/EC of 13December 2004 implementing the principle of equal treatment between women and men in the access to andsupply of goods and services and Directive 2006/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July2006 on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women inmatters of employment and occupation. However, the European Court of Justice found in several cases (seeAppendix I) that that discrimination against people who intend to undergo, are undergoing or have undergone“gender reassignment” may amount to sex discrimination. Such protection is narrower than what would beprovided on grounds of gender identity. Gender identity cannot in fact be construed as referring exclusively to“gender reassignment” and protection under EU law should be extended to cover the full range of genderidentity and expression.

1.1 THE RIGHTS TO PRIVATE LIFE AND TO RECOGNITION BEFORE THE LAWTransgender individuals whose official documents do not reflect their gender identity, nameor gender expression must disclose they are transgender every time they produce thesedocuments. In many countries, this is almost a daily occurrence. In situations where officialdocuments are required to obtain goods or services – for example, in finding employment,enrolling in education, obtaining housing, or claiming welfare benefits – transgenderindividuals are forced to give up aspects of their right to private life in order to obtain them.A 20-year-old transgender man in Finland said:“I still have a female name and identitynumber, and I have had problems with my ID. For instance, almost every time I try to collecta parcel from the post office, they question whether the passport is mine. Also, the travelcard has my identity number on it and when I try to get on a bus, the driver often claims it isnot my card as it says female.”26

26 This person expressed the wish to remain anonymous.

Amnesty International January 2014

Index: EUR O1/001/2014

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

21

It is vital that states allow transgender people to change their gender markers and their nameon all documents, in order to protect their right to private life. Those states that have not putin place a procedure to ensure legal gender recognition of transgender people, includingIreland, or those where legislative gaps make it impossible for transgender people to obtaindocuments reflecting their gender identity, including Lithuania,27violate their right to privatelife. This right is protected by international and regional human rights standards includingthe International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, Article 17) and the EuropeanConvention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR, Article8). The European Court of Human Rights has found states to be in breach of Article 8 of theECHR in several instances where transgender individuals were not allowed to obtain legalrecognition of their gender.The impossibility to obtain documents that reflect gender identity and expression may alsoconstitute a violation of the transgender individuals’ right to recognition before the law, whichis protected under international human rights law, including by the ICCPR (Article 16) andthe Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW,Article 15).28The rights to private life and to recognition before the law may also be violated by stateswhere procedures on legal gender recognition exist but are overly lengthy and/or containmandatory criteria to be fulfilled that in effect exclude some groups of transgender people.Such exclusion could occur, for example, when the procedures require medical treatments,including surgeries, that some transgender people cannot undergo because of health relatedproblems, and where access to these procedures is contingent on the individual receiving aspecific psychiatric diagnosis.

1.2 THE RIGHT TO THE HIGHEST ATTAINABLE STANDARD OF HEALTH AND TO BEFREE FROM CRUEL, INHUMAN AND DEGRADING TREATMENTIn recent years, some positive changes have occurred in a few European countries includingthe Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden. Legislative reforms enacted in these countrieshave abolished some of the problematic requirements imposed on transgender individuals to

27 In Lithuania, Article 2.27, para1 of the Civil Code adopted in 2001, provides that an unmarried adult of full age has the right to “change the designation of sex” if itis medically possible. Article 2.27, para .2, states that the conditions and the procedure for “changing the designation of sex”, shall be prescribed by law. As such alaw was never adopted, transgender people in Lithuania cannot obtain legal recognition of their gender. Civil Code available in English here:http://www3.lrs.lt/pls/inter3/dokpaieska.showdoc_l?p_id=245495, accessed 2 January 2013. In 2007, the European Court of Human Rights found in L. v Lithuaniathat this gap amounted to a violation of the applicant’s right to private and family life (Article 8). The applicant, a transgender man, had undergone some genderreassignment surgeries but could not undergo genital reassignment surgery, as it was not available in Lithuania. As a result, the applicant could not change his personalcode, mentioned on his birth certificate and passport, which indicated that he was legally a female (the code started with the digit 4 for female; males are assigned thedigit 3).28 Yogyakarta Principles on the applications of human rights Law in relation to sexual orientation and gender identity, Principle 3. The Human Rights Committee,tasked to monitor the implementation of the ICCPR, found in several instances that the state’s failure to issue birth certificates or to keep civil registries amounted to aviolation of Article 16 and led to the violation of other rights included access to social services or education. See for example: Concluding Observations on Albania,CCPR/CO/82/ALB (HRC, 2004), para. 17, Concluding Observations on Bosnia and Herzegovina, CCPR/C/BIH/CO/1 (HRC, 2006), para. 2, Concluding Observations onthe Democratic Republic of Congo, CCPR/C/COD/CO/3 (HRC, 2006), para 25.

Index: EUR 01/001/24

Amnesty International January 2014

22

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

obtain legal gender recognition, including sterilization.29Moreover, in 2011, the GermanConstitutional Court found that the irreversible surgery and the sterilization requirementsforeseen by domestic legislation on legal gender recognition were unconstitutional.30In 2009the Austrian Constitutional Court found that genital surgeries should not have been aprerequisite to allow transgender people to change their names.31However, legal gender recognition procedures in the majority of European countries requirethe individual to fulfil a strict set of criteria. In many cases, these requirements violate thehuman rights of transgender individuals, including the rights to the highest attainablestandard of health and to be free from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. Transgenderindividuals are thus forced to choose between these rights and the rights to private life andrecognition before the law outlined above.In many countries, transgender individuals cannot obtain legal gender recognition unless theyundergo psychiatric assessment and receive apsychiatric diagnosis.The World HealthOrganization (WHO) currently categorizes “gender identity disorders” under “mental andbehavioral disorders”32in its International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10thversion,adopted on 17 May 1990). In addition, the fifth version of the Diagnostic and StatisticalManual of Mental Health Disorders (DSM-V) of the American Psychiatric Association (APA),adopted in 2013, includes “gender dysphoria” in the list of mental disorders.33

29 In Spain, a new law (3/2007 of 15 March) was adopted in 2007 that requires psychiatric diagnosis and medical treatments, and excludes minors from its scope,but it does not require genital reassignment surgery and sterilization, http://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2007/03/16/pdfs/A11251-11253.pdf, in Spanish, accessed 2 January2013. In Portugal a new law (7/2011 of 15 March) was adopted in 2011 that requires psychiatric diagnosis and excludes minors from its scope, but it does not includeother compulsory medical requirements, http://dre.pt/pdf1sdip/2011/03/05200/0145001451.pdf, in Portuguese, accessed 2 January 2013. In Sweden, a new law onlegal gender recognition, which entered into force on 1 July 2013 (SFS 2013: 405), requires transgender people to have lived in accordance with their gender identity“since a long time” and excludes minors from its scope, but it abolished the sterilization requirement included in the previous legislation adopted in 1972,http://rkrattsdb.gov.se/SFSdoc/13/130405.PDF, in Swedish, accessed 2 January 2013. For legislative changes in Netherlands see note 2.30 See chapter 2.6.2.3.

31 Verfassungsgerichtshof/B1973/08, judgment of 3 December 2009. In 2006 the Constitutional Court had annulled an internal order issued by theMinistry of Interior in 2006 (Transsexuellen Erlass) according to which transgender people could have changed their name only after having compliedwith several medical requirements and having changed their sex in the Register of Births, which was possible only for transgender people who were notmarried. Verfassungsgerichtshof/B947/05, judgment of 21 June 2006.

32 ICD-10, Chapter V, Mental and Behavioural Disorders, F64 Gender Identity Disorders. Gender Identity Disorders include: transsexualism (F64.0),dual-role transvestism (F64.1), gender identity disorders of the childhood (F64.2), other gender identity disorders (F64.8), gender identity disorder,unspecified (F64.9), http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en#/F60-F69, accessed 4 December 2013. The American PsychiatricAssociation (APA) removed “homosexuality” from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders (DSM) in 1973. It took almost 20more years for the World Health Organization (WHO) to depathologize “homosexuality”, which it deleted from the International Classification of Diseases(ICD) on 17 May 1990. For further details, see appendix II.

33 According to the DSM-IV, “For a person to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria, there must be a marked difference between the individual’s expressed/experiencedgender and the gender others would assign him or her, and it must continue for at least six months. In children, the desire to be of the other gender must be present

Amnesty International January 2014

Index: EUR O1/001/2014

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

23

The psychiatric diagnosis is very often based on these categories. In some countries,including Denmark, Finland and Norway, access to medical treatments necessary to obtainlegal gender recognition, including surgeries, is made contingent on the specific and narrowlydefined diagnosis of transsexualism (F64.0, See Appendix II). Transgender people who arediagnosed with other “gender identity disorders” included in the ICD-10thversion, cannotaccess such treatments and are eventually excluded from the possibility of obtaining legalrecognition of their gender, unless if they access treatments privately or abroad.In countries where legal gender recognition is contingent on obtaining such a diagnosis,individuals who wish their gender identity to be reflected on official documents must submitto a notion that their transgender status – the fact that their gender identity does not accordwith the gender they were assigned at birth – is a mental disease. Most of the transgenderpeople Amnesty International spoke to for this report expressed the view that psychologicalcounselling would be helpful before and during the transitioning phase. However, thepsychiatric diagnosis is a practice many transgender people find demeaning as well asunnecessary for the purposes of obtaining legal gender recognition. In some states, includingDenmark, France and Germany, transgender people have to undergo psychiatric diagnosiseven if they simply want to change their name.Ely, a trans man living in Belgium, said: “Ofcourse, trans people have the right to see apsychiatrist if they want too… What is wrong is the [idea that] you need a psychiatric opinionto be who you want to be.”34In 2010, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), in urging theworldwide depathologization of gender non-conformity, stated: “The expression of gendercharacteristics, including identities, that are not stereotypically associated with one’sassigned sex at birth is a common and culturally diverse human phenomenon [that] shouldnot be judged as inherently pathological or negative.”35In fact, the reality of the psychiatric diagnosis requirement is that medical professionals aremaking decisions on identity features that are personal and do not manifest themselves in auniform and consolidated pattern. Transgender people who spoke to Amnesty Internationalgenerally felt the diagnosis was based on gender stereotypes. Charlie, a transgender manliving in Denmark, said: “Youhave to try to convince [the mental health professionals] thatyour transgender identity is not a whim. They kept asking whether I was sure that I was not alesbian and whether I had tried to do this or that to live as a woman. They were mainly

and verbalized. This condition causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning,”http://www.psych.org/practice/dsm/dsm5, accessed 4 December 2013.For further information, see the APA factsheet on “gender dysphoria”,http://www.dsm5.org/Documents/Gender%20Dysphoria%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf, accessed 20 December 2013.34 Interview with Ely, 18 December 2013.35 WPATH, World Professional Association for Transgender Health, Board of Directors, 2010, WPATH De-Psychopathologisation Statement,http://tgmentalhealth.com/2010/05/26/wpath-releases-de-psychopathologisation-statement-on-gender-variance/WPATH, Standards of Care (SOC) for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Non-conforming People, 7th Version, p. 4,http://www.wpath.org/uploaded_files/140/files/Standards%20of%20Care,%20V7%20Full%20Book.pdf

Index: EUR 01/001/24

Amnesty International January 2014

24

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

interested in what I liked in bed. They asked me how often I masturbated, if I wanted to bethe dominant partner in bed. You constantly feel you have to give the right answer… that youare under examination. When I said that I was sexually dominant, he [the mental healthprofessional] said I could be a man because that was a typical masculine behaviour. Hisapproach was very black or white.”36The United Nations Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination againstWomen (CEDAW) requires states to ensure that state policies and practices are not based on,or have the effect of reinforcing, gender stereotypes. According to Article 5a of theConvention, states should take measures to: “modify the social and cultural patterns ofconduct of men and women, with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices andcustomary and all other practices which are based on the idea of the inferiority or thesuperiority of either of the sexes or on stereotyped roles for men and women.”In several European countries, including Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy37and Norway,transgender people cannot obtain new documents reflecting their gender identity unless theyundergogenital reassignment surgeries.Depending on the nature of the surgical procedureperformed, these procedures could also have the effect of removing the individual’sreproductive ability.Although some transgender people would like to access certain health treatments with theaim of modifying their bodies, many others do not. For those who do, their choices in termsof the treatments they would like to access – whether hormone therapy, surgeries, genitalreassignment surgeries, voice therapy, depilation and so on – greatly vary and depend on thepersonal feelings and perceptions shaping their gender identity. It is therefore problematicwhen a set course of medical treatment is required of all transgender people as aprecondition to obtaining legal recognition of their gender.Luca, a transgender man from Norway, told Amnesty International: “Iwant my legal gender tobe male but I still have the female one. I can in theory obtain recognition of my gender butonly if I am sterilized. This is out of question for me and it is not going to happen. After I hadbeen taking hormones for a year the doctor told me that the next step would involve removingmy ovaries and uterus. I told him I did not want that kind of surgery. I feel like I am deprivedof my rights [legal gender recognition] just because I choose to exercise some other rights[refuse medical treatments].”38Requiring transgender people to undergo unnecessary medical treatments to obtain legalgender recognition violates their right to the highest attainable standard of health, which is

36 Interview with Charlie (pseudonym), 4 November 2013.37 According to Italian legislation legal gender recognition is permitted only insofar as sexual characteristics have been adjusted through medico-surgical treatmentsthat had been authorized in advance by the courts. Law of 14 April 1982, no. 164, Provisions concerning the rectification of sex attribution (Norme in material direttificazione di attribuzione di sesso), Article 3, http://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:legge:1982-04-14;164, in Italian, accessed 3 January 2013.38 Interview with Luca, Oslo, 24 June 2013.

Amnesty International January 2014

Index: EUR O1/001/2014

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

25

protected under international human rights law, including by the UN Covenant on Economic,Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR, Article 12). The Committee on Economic, Social andCultural Rights, which monitors the implementation of the CESCR, has stated: “The right tohealth contains both freedoms and entitlements. The freedoms include the right to controlone’s health and body, including sexual and reproductive freedom, and the right to be freefrom interference, such as the right to be free from torture, non-consensual medicaltreatment and experimentation. By contrast, the entitlements include the right to a system ofhealth protection which provides equality of opportunity for people to enjoy the highestattainable level of health.”39The Yogyakarta Principles require that: “Noperson may be forced to undergo any form ofmedical or psychological treatment, procedure, testing, or be confined to a medical facility,based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Notwithstanding any classifications to thecontrary, a person’s sexual orientation and gender identity are not, in and of themselves,medical conditions and are not to be treated, cured or suppressed.”40In many cases, genital reassignment surgeries result insterilizationas they involve theremoval of either the testes, for people who are transitioning towards the female gender, orthe uterus and ovaries, for those who are transitioning towards the male gender. But this goesfurther in some countries, where legal gender recognition is dependent on a sterilizationrequirement. Whether explicitly prescribed by law such as in Belgium, Denmark and Finland,or stemming from established practices such as in Norway or France, the sterilizationrequirement violates the right of transgender people to be free from inhuman, cruel ordegrading treatment, which is protected under several international human rights instrumentsincluding the ICCPR (Article 7) and the UN Convention against Torture and Inhuman, Cruelor Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Article 16). This requirement results also in theimpossibility for transgender people to found a family and thus violates their right to privateand family life (See chapter 1.2).In 2013, the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and inhuman, cruel or degrading treatment orpunishment stated: “In many countries transgender persons are required to undergo oftenunwanted sterilization surgeries as a prerequisite to enjoy legal recognition of their preferredgender. In Europe, 29 States require sterilization procedures to recognize the legal gender oftransgender persons.” The Rapporteur called upon states to put an end to these practices.41

39 General Comment 14: the right to the highest attainable standards of health, 11 August 2000, para8.40 Principle 18: protection against medical abuse41 A/HRC/22/54, the Rapporteur recommends states put an end to involuntary sterilization stemming from genital reassignment surgeries transgender people have toundergo if they want to obtain legal recognition of their gender, 1 February 2013,http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session22/A.HRC.22.53_English.pdf

Index: EUR 01/001/24

Amnesty International January 2014

26

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

1.3 THE RIGHT TO MARRY AND TO FOUND A FAMILY AND THE RIGHT TO FAMILYLIFE

In countries such as Italy42or Finland, legal gender recognition is contingent onchanges inmarital status.This requirement discriminates against transgender individuals who aremarried/in a civil partnership and wish to remain so, as they are bound to choose betweentheir rights to marry and to found a family and to respect for private and family life, and theirright to recognition before the law.The single status requirement was included in the General Scheme of the GenderRecognition Bill 2013, published by the Irish government in July 2013 (see Chapter2.4.3.1). Patricia is a transgender woman married to Susan and living in Cork, Ireland. Shesaid: “It’snot up to other people to evaluate my marriage, it should be my choice. The factthat other people, outside of our union, can decide that we should divorce, that our marriageshould end or not… is a violation of our rights. We’re already married. I’m the same person Iwas when I got married. The only thing that’s changing is the gender marker on my birthcertificate.”43The right to marry and to found a family is protected under international and regional humanrights laws including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, Article23) and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR, Article 12). The right to respectfor private and family life is protected by the ICCPR (Article 17) and the ECHR (Article 8).The European Court of Human Rights has clarified that the notion of private and family lifeequally applies to same-sex couples, irrespective of the legal regime applicable to themunder domestic jurisdiction.44Moreover, the single status requirement does not comply with the Yogyakarta Principles,which state: “No status, such as marriage or parenthood, may be invoked as such to preventthe legal recognition of a person’s gender identity.”45Some states argue that requiring transgender people to be single if they wish to obtain legalrecognition of their legal gender stems from the prohibition on civil marriages between same-sex individuals in their jurisdictions. However, this aim, which is discriminatory in itself,cannot justify restricting the family and marriage rights of transgender people. States shouldin fact ensure the enjoyment of all human rights, including the right to marry and to found of

42 Law 164/1982, Article 4. Legal gender recognition automatically entails the cessation of marriage.43 Interview with Susan and Patricia, Cork, Ireland, 24 October 2013.44 For example the Court found in the case Schalk and Kopf v Austria that the reference to "men and women" in the ECHR no longer means that "the right to marryenshrined in Article 12 must in all circumstances be limited to marriage between two persons of the opposite sex." The court also stated: “[I]t is artificial to maintainthe view that, in contrast to a different-sex couple, a same-sex couple cannot enjoy ‘family life’ for the purposes of Article 8.” See, Schalk and Kopf v Austria,Application no. 30141/04, para94.45 Yogyakarta Principles, “The application of international human rights law to sexual orientation and gender identity, Principle 3(d): the right to equal recognition beforethe law”, http://www.yogyakartaprinciples.org/principles_en.htm

Amnesty International January 2014

Index: EUR O1/001/2014

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

27

family, without discrimination, including on grounds of sexual orientation and genderidentity.As the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe has noted, courts in somestates that do not recognise marriage between same-sex partners have nonetheless decided infavour of allowing marriages to continue when one partner has changed gender. Such rulings,the Commissioner notes, recognize that “protecting all individuals without exception fromstate-forced divorce has to be considered of higher importance than the very few instances inwhich this leads to same-sex marriages. This approach is to be welcomed as it ends forceddivorce for married couples in which one of the partners is transgender”.46Because of the requirement of single status, people who are married or in a civil partnershipand seek recognition of their preferred gender will face an invidious choice. They must eithergive up the legal protection acquired in their union, which is a violation of their right and theright of their partners and children to private and family life, or forego legal recognition oftheir preferred gender, a violation or their right to private life and to recognition before thelaw.

1.4 THE BEST INTEREST OF THE CHILDIn some countries,age restrictionson legal gender recognition are prescribed by law (Finland,Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the Netherlands) or result from current practices (Belgium,Denmark). Absolute denial of legal gender recognition to individuals under a given age is notconsistent with existing international standards regarding the rights of children. Legal genderrecognition should be accessible to children on the basis of their best interest and taking intoaccount their evolving capacities.The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) requires states to respect the right ofchildren to be heard and to duly take into account their views. A key requirement of the CRCis that: “in all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private socialwelfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the bestinterests of the child shall be a primary consideration.”47The UN Committee on the Rightsof the Child has highlighted that the identity of the child includes characteristics such assexual orientation and gender identity, and that “[…] the right of the child to preserve his orher identity is guaranteed by the Convention (Article 8) and must be respected and taken intoconsideration in the assessment of the child’s best interests.”48This is closely linked to the right of children to express their views freely and to have thoseviews taken into account in matters affecting them.49As the Committee on the Rights of theChild has noted: “Assessment of a child’s best interests must include respect for the child’s

46 CommDH/IssuePaper(2009)2, Human Rights and Gender Identity, para. 3.2.2.47 Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 3.1.48 Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment 14: The right of the child to have his or her best interests taken as a primary consideration (Article 3, para.1), para. 55, 2013.49 Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 12.1.

Index: EUR 01/001/24

Amnesty International January 2014

28

The state decides who I amLack of legal gender recognition for transgender people in Europe

right to express his or her views freely and due weight given to said views in all mattersaffecting the child.”50The right of children to express their own views regarding what is in their best interests isespecially important in relation to older children, in light of their evolving capacities. As theCommittee on the Rights of the Child has emphasized that “…the child’s views must begiven due weight, whenever the child is capable of forming her or his own views. In otherwords, as children acquire capacities, so they are entitled to an increasing level ofresponsibility for the regulation of matters affecting them.”51Transgender children and particularly adolescents who are unable to obtain legal recognitionof their gender may face further discrimination and harassment, for instance at school wherethey cannot be enrolled in accordance with their gender identity. Andy, an 18-year-oldtransgender man living in Ireland, said:“For me [legal gender recognition] is something toback me up… and make sure that teachers and the headmaster accept my gender and allowme to use the [male] bathroom.”52