Sundheds- og Forebyggelsesudvalget 2011-12

L 185

Offentligt

IS S N 1606- 1691

IS S N 0000- 0000

EMCDDA

MONOGRAPHSHarm reduction:evidence, impacts and challenges

EMCDDAMONOGRAPHSHarm reduction:evidence, impacts and challenges

EditorsTim Rhodes and Dagmar Hedrich

Legal noticeThis publication of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA)is protected by copyright. The EMCDDA accepts no responsibility or liability for anyconsequences arising from the use of the data contained in this document. The contents ofthis publication do not necessarily reflect the official opinions of the EMCDDA’s partners,the EU Member States or any institution or agency of the European Union or EuropeanCommunities.A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. Itcan be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu).

Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questionsabout the European UnionFreephone number (*):00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11(*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed.

Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication.Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2010ISBN 978-92-9168-419-9doi: 10.2810/29497� European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2010Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.Printed in SpainPrinted on white chlorine-free PaPer

Cais do Sodré, 1249-289 Lisbon, PortugalTel. (351) 211 21 02 00 • Fax (351) 218 13 17 11[email protected] • www.emcdda.europa.eu

ContentsForewordAcknowledgementsPreface71113

IntroductionChapter 1:Harm reduction and the mainstreamTim Rhodes and Dagmar Hedrich19

Part I:Chapter 2:

BackgroundThe diffusion of harm reduction in Europe and beyondCatherine Cook, Jamie Bridge and Gerry V. Stimson37

Chapter 3:

The development of European drug policy and the place of harmreduction within thisSusanne MacGregor and Marcus Whiting59

Chapter 4:

Perspectives on harm reduction — what experts have to sayHarm reduction in an open and experimenting societyJürgen Rehm and Benedikt FischerHCV prevention—a challenge for evidence-based harm reductionMatthew HickmanBroadening the scope and impact of harm reduction for HIV prevention,treatment and care among injecting drug usersAndrew BallTranslating evidence into action — challenges to scaling upharm reduction in Europe and Central AsiaRifat Atun and Michel KazatchkinePeople who use drugs and their role in harm reductionMat SouthwellHarm reduction — an ‘ethical’ perspectiveCraig FryThe ambiguity of harm reduction — goal or means,and what constitutes harm?Robin Room

797985

89

94101104

108

Part II:Chapter 5:

Evidence and impactsHarm reduction among injecting drug users — evidenceof effectivenessJo Kimber, Norah Palmateer, Sharon Hutchinson,Matthew Hickman, David Goldberg and Tim Rhodes115

Chapter 6:

The effect of epidemiological setting on the impact of harm reductiontargeting injecting drug usersPeter Vickerman and Matthew Hickman165

Chapter 7:

The fast and furious — cocaine, amphetamines and harm reductionJean-Paul Grund, Philip Coffin, Marie Jauffret-Roustide,Minke Dijkstra, Dick de Bruin and Peter Blanken

191

Chapter 8:

Harm reduction policies for cannabisWayne Hall and Benedikt Fischer

235

Chapter 9:

Harm reduction policies for tobaccoCoral Gartner, Wayne Hall and Ann McNeill

255

Chapter 10:

Alcohol harm reduction in EuropeRachel Herring, Betsy Thom, Franca Beccaria,Torsten Kolind and Jacek Moskalewicz

275

Part III:Chapter 11:

Challenges and innovationsDrug consumption facilities in Europe and beyondDagmar Hedrich, Thomas Kerr and Fran§oise Dubois-Arber305

Chapter 12:

User involvement and user organising in harm reductionNeil Hunt, Eliot Albert and Virginia Montañés Sánchez

333

Chapter 13:

Young people, recreational drug use and harm reductionAdam Fletcher, Amador Calafat, Alessandro Pirona andDeborah Olszewski

357

Chapter 14:

Criminal justice approaches to harm reduction in EuropeAlex Stevens, Heino Stöver and Cinzia Brentari

379

Chapter 15:

Variations in problem drug use patterns and their implicationsfor harm reductionRichard Hartnoll, Anna Gyarmathy and Tomas Zabransky405

ConclusionsChapter 16:Current and future perspectives on harm reduction in theEuropean UnionMarina Davoli, Roland Simon and Paul Griffiths437

ContributorsAbbreviationsFurther reading

449455461

ForewordIt is with great pleasure that I introduce the EMCDDA´s latest Scientific monograph, whichprovides a state-of-the-art review of the role of harm reduction strategies andinterventions. Harm reduction has become an integral part of the European policy debateon drugs, but this was not always the case. Although harm reduction approaches have along history in the addictions field and in general medicine, our modern concept of harmreduction has its roots in the challenges posed by the rapid spread of HIV infectionamong drug injectors in the mid-1980s. Initially, there was considerable controversysurrounding the notion that preventing the spread of HIV was of paramount importanceand required immediate and effective action, even if this meant that abstinence as atherapeutic goal had to take second place.In Europe today, that controversy has to a large extent been replaced by consensus. Thisreflects not only a general agreement on the value of the approach but also recognition thatnational differences in interpretation and emphasis exist. Harm reduction as a concept is nowaccepted as part of abalanced approach,an integral element of a comprehensive strategythat includes prevention, treatment, social rehabilitation and supply reduction measures. This,I would argue, is a strong endorsement of the pragmatic and evidence-based approach thatEuropean drug policies have come to embrace.It would be wrong to overstate this position; the drug debate remains an ideological as wellas a scientific one. Nonetheless, the evidence that needle exchange and substitution treatmentcan be effective elements in a strategy to reduce HIV infection among injectors, andimportantly that these interventions do not lead to greater harms in the wider community, hashad a significant impact on European drug policies and actions. Although it would be wrongto minimise the continuing problem that we face, when comparing Europe to many otherparts of the world it is clear that overall our pragmatic approach has borne fruit. Argumentsmay still exist about the relative role played by different types of interventions, but mostinformed commentators would now agree that harm reduction approaches have beeninfluential in addressing the risks posed by drug injecting in Europe over the last 20 years.This is, then, an appropriate moment to take stock of existing scientific evidence on harmreduction and consider the issues that we will need to tackle in the future. The evidence forsome harm reduction interventions is relatively robust. For others, methodological difficultiesmake generating a solid evidence base difficult, and the current scientific bases for guidingpolicymaking need to be strengthened.The assertion that the concept of harm reduction is an accepted part of the European drugpolicy landscape does not mean that all interventions that fall under this heading are eitherwidely supported or endorsed. Many areas of controversy remain, and one purpose of thismonograph is to chart where the current fault lines now lie, with the hope that future studieswill provide a sounder basis for informed actions. Moreover, and perhaps more importantly,the drug problems and issues we face in Europe today are very different to those we7

Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges

struggled with in the past. HIV remains an important issue, but it is no longer thepredominant one. From a quantitative public health point of view, drug overdose, HCVinfection, and other psychiatric and physical co-morbidities are becoming of equal or evengreater importance. In addition, drug injecting levels appear to be falling and patterns ofdrug taking are become more complex and are increasingly characterised by theconsumption of multiple substances, both licit and illicit.What role will harm reduction have within this new landscape? This monograph begins toexplore that question, as we consider how harm reduction strategies may be a usefulcomponent of our approach to the challenges that drug use in twenty-first century Europe willbring. I strongly believe that in taking drug policy forward we have a duty to learn from thepast, and that ideological positions should not stand in the way of a cool-headed analysis ofthe evidence. In the future this is likely to become imperative both to those who instinctivelysupport harm reduction approaches, and to those who instinctively oppose them. Thismonograph makes an important contribution to the debate by highlighting where we arenow, and considering how we have got here. It also draws our attention to some of thechallenges that lie ahead, if we are to understand the role and possible limits of harmreduction approaches to future European drug policies.Wolfgang GötzDirector, EMCDDA

8

AcknowledgementsThe EMCDDA would like to thank all authors, editors and reviewers who have worked on thispublication. In particular, the monograph benefited from overall editorial input by TimRhodes and Dagmar Hedrich. A special mention goes to the members of the internalcoordination group who accompanied the project from inception to publication — namely toAlessandro Pirona and Anna Gyarmathy; as well as to the planning group: Roland Simon,Rosemary de Sousa, Paul Griffiths, Julian Vicente and Lucas Wiessing. The EMCDDAgratefully acknowledges the contributions from many unknown external reviewers and fromthe reviewers drawn from the EMCDDA’s Scientific Committee. Furthermore, valuable reviewcomments and input were received from EMCDDA staff members Marica Ferri, BrendanHughes, André Noor, Cécile Martel, Luis Prieto and Frank Zobel. Vaughan Birbeck providedmuch appreciated help with bibliographic references, and Alison Elks of Magenta Publishingedited the final publication.

11

PrefaceHarm reduction is now positioned as part of the mainstream policy response to drug usein Europe. However, this has not always been the case, and in reflecting on this fact wefelt that the time was right to take stock of how we had arrived at this position, ask what itmeans for both policies and action, and begin to consider how harm reduction is likely todevelop in the future.This monograph builds on other titles in the EMCDDA’s Scientific monographs series,where we have taken an important and topical subject, assembled some of the bestexperts in the field, and allowed them to develop their ideas constrained only by theneed to demonstrate scientific rigour and sound argument. Our Scientific monographs areintended to be both technically challenging and thought provoking. Unlike our otherpublications we take more of an editorial ‘back seat’ and we do not seek consensus ornecessarily to produce a balanced view. Good science is best done when unconstrained,and best read with a critical eye.This volume includes a variety of perspectives on harm reduction approaches, togetherwith an analysis of the concept’s role within drug policies, both in Europe and beyond.Readers may not necessarily agree with all of the arguments made or the conclusiondrawn, but we hope it is perceived as a valuable contribution to the ongoing debate onhow to respond to contemporary drug problems in Europe.A number of contributors explore what harm reduction means and what policies it canencompass, as well as charting how the concept evolved. They reflect on the point wehave now reached in terms of both harm reduction practice and the evidence base for itseffectiveness. A major issue that many contributors touch on is the difficulty of assessinghow complex interventions occurring in real world settings can be evaluated, and whyconclusive evidence in such settings can be so elusive.With an eye to the future, we also asked our contributors to wrestle with the difficultissue of how harm reduction might be extended into new areas that are of particularrelevance to the evolving European drug situation. Here the empirical base forgrounding discussions is far less developed, and a more exploratory approach isnecessary.As a European agency, the EMCDDA has a somewhat unique perspective on thedevelopment of the drugs debate within the European Union. It is therefore appropriatefor us to make our own introductory remarks about the mainstreaming of the concept ofharm reduction at the European level, as opposed to the national one. Thisdevelopment, we would argue, is sometimes misunderstood, as there is a tendency bysome commentators to polarise the position and focus exclusively on either thedifferences, or alternatively the commonalities, that exist between Member States intheir drug policies. Europe is closer now than it once was in terms of how it responds to13

Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges

and views drug use, but differences still exist, reflecting national policy perspectives,cultural differences and, to some extent, simply a different experience of the drugproblem.Despite these differences in opinion and experience, there is a general consensus thatabstinence-orientated drug policies need to be supplemented by measures that candemonstrably reduce the harms that drug users are exposed to. This consensus isstrongest in the area of reducing HIV infection among injectors — although even herethere is disagreement on the appropriateness of which interventions might fall under thisgeneral heading. It is also the case that the range and intensity of harm reductionservices available in EU Member States varies considerably. Therefore, the observationthat harm reduction has played an important part in achieving the relatively positiveposition that the EU has achieved with respect to HIV infection among injectors has to betempered with the comment that some countries have maintained low rates of infectionsamong injecting drug users where the availability of harm reduction services has beenlimited.In summary, considerable debate still exists at European level on the appropriateness ofdifferent approaches, and some interventions, such as drug consumption rooms, are stillhighly contentious. However, Europe’s policy debate in this area appears now to be amore pragmatic one in which harm reduction policies are not automatically considered toconflict with measures intended to deter drug use or promote abstinence. Rather, theconsensus is increasingly moving towards a comprehensive, balanced and evidence-based approach that seamlessly includes harm reduction alongside prevention, treatmentand supply reduction measures.This monograph is comprehensive in its scope. It covers interventions that are stillcontroversial and ones that have become so mainstream that many might now find it hardto believe that this has not always been the case. We have included voices from the usercommunity, as activism has historically been an important element in the development ofthis perspective. The monograph also addresses new challenges for a harm reductionapproach, such as alcohol and tobacco use and Europe’s growing appetite for stimulantdrugs.The EMCDDA is grateful that so many experts were prepared to assist us with this work,often tackling new and demanding topics. This task would have been infinitely moredifficult if we had not benefited from having a first-class editorial team working on thisproject. We are indebted to our editors, Tim Rhodes and Dagmar Hedrich, who bothplayed a major role in conceptualising, planning and implementing this project andwithout whose input this document would have been a far less comprehensive andimpressive achievement.It is important to note that the voices presented here are not those of the EMCDDA orthe European institutions. As with other Scientific monographs, the intention is toprovide a forum for stimulating debate and collecting high-quality scientific opinion andinformed comment on a topic of contemporary relevance. The monographs are14

Preface

intended to be of particular interest to a specialist audience and therefore some of thepapers in this collection are highly technical in nature. All papers presented here havebeen peer-reviewed to ensure an appropriate degree of scientific rigour, but the viewsexpressed by the authors remain their own.The EMCDDA’s role is as a central reference point on drug information within theEuropean Union. We are policy neutral; our task is to document and report, and never toadvocate or lobby. This neutrality is important when we address any drug use issue, asthis is an area where so many have passionate and deeply held views. However, it isparticularly important when we address a topic like harm reduction, where perspectivesare sometimes polarised and there are those on all sides of the drugs debate that see alinkage between this subject and broader issues about how societies control drugconsumption. The rationale for our work is that, over time, better policy comes fromdebate informed by a cool-headed and neutral assessment of the information available.Many of the contributors to this report are passionate and committed in their views; theyalso provide a wealth of data, analysis and argumentation. They do not speak with acommon voice, and we do not necessarily endorse all the conclusions drawn, but takencollectively we believe they make a valuable contribution to a better understanding of atopic that has become an important element in contemporary drug policies.Paul Griffiths and Roland SimonEMCDDA

15

Introduction

Chapter 1Harm reduction and the mainstreamTim Rhodes and Dagmar Hedrich

AbstractHarm reduction encompasses interventions, programmes and policies that seek to reducethe health, social and economic harms of drug use to individuals, communities and societies.We envisage harm reduction as a ‘combinationintervention’,made up of a package ofinterventions tailored to local setting and need, which give primary emphasis to reducingthe harms of drug use. We note the enhanced impact potential derived from deliveringmultiple harm reduction interventions in combination, and at sufficient scale, especiallyneedle and syringe distribution in combination with opioid substitution treatmentprogrammes. We note that harm reduction is a manifestation of mainstream public healthapproaches endorsed globally by the United Nations, and in the EU drugs strategy andaction plans, and features as an integral element of drug policy in most of the Europeanregion. However, we note evidence that links drug harms to policies that emphasise strictlaw enforcement against drug users; an unintended consequence of international drugcontrol conventions. The continuum of ‘combination interventions’ available to harmreduction thus extends from drug treatment through to policy or legal reform and theremoval of structural barriers to protecting the rights of all to health. We end by introducingthis monograph, which seeks to reflect upon two decades of scientific evidence concerningharm reduction approaches in Europe and beyond.

IntroductionHarm reduction encompasses interventions, programmes and policies that seek to reducethe health, social and economic harms of drug use to individuals, communities andsocieties. A core principle of harm reduction is the development of pragmatic responses todealing with drug use through a hierarchy of intervention goals that place primaryemphasis on reducing the health-related harms of continued drug use (Des Jarlais, 1995;Lenton and Single, 2004). Harm reduction approaches neither exclude nor presume atreatment goal of abstinence, and this means that abstinence-oriented interventions canalso fall within the hierarchy of harm reduction goals. We therefore envisage harmreduction as a ‘combinationintervention’,made up of a package of interventions tailoredto local setting and need that give primary emphasis to reducing the harms of drug use. Inrelation to reducing the harms of injecting drug use, for example, this combination ofinterventions may draw upon needle and syringe programmes (NSPs), opioid substitutiontreatment (OST), counselling services, the provision of drug consumption rooms (DCRs),peer education and outreach, and the promotion of public policies conducive to protectingthe health of populations at risk (WHO, 2009).19

Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges

Harm reduction as mainstream public healthHarm reduction in the drugs field has a long history, variably traced back to the prescriptionof heroin and morphine to people dependent on opioids in the United Kingdom in the 1920s(Spear, 1994), the articulation of public health concerns of legal drugs, alcohol and tobacco,and the introduction of methadone maintenance in the United States in the 1960s (Bellis,1981; Erickson, 1999). By the 1970s, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendedpolicies of harm reduction to ‘prevent or reduce the severity of problems associated with thenon-medical use of dependence-producing drugs’, noting that this goal is at once ‘broader,more specific’ as well as ‘more realistic’ than the prevention of non-medical use per se inmany countries (WHO, 1974; Ball, 2007).The concepts of risk and harm reduction are closely aligned to that of health promotion andpublic health more generally. Yet in relation to illicit drugs, debates about developing publichealth approaches to reducing drug-related harms are often clouded by harm reductionpositioned as a symbol of radical liberalisation or attack upon traditional drug control. Publichealth has at its core the idea of protecting individual and population health through thesurveillance, identification and management of risk to health (Ashton and Seymour, 1988;Peterson and Lupton, 1996). It is essentially a model of risk and harm reduction. The new publichealth movement of the mid-1980s coincided with the emergence of human immunodeficiencyvirus (HIV) epidemics in many countries. This new vision of public health was heralded as a shiftbeyond narrowly defined biomedical understandings towards one that envisaged health andharm as also products of the social and policy environment, and which gave greater emphasisto community-based and ‘low-threshold’ interventions (WHO, 1986). Contemporary publichealth thus characterises risk and health decision-making as a responsibility of health consciousindividuals whilst also emphasising the significance of the social environment in producing harmand in shaping the capacity of individuals and communities to avoid risk (Peterson and Lupton,1996; Rhodes, 2002). Consequently, mainstream public health approaches recognise the needto create ‘enabling environments’ for risk reduction and behaviour change, including throughthe strengthening of community actions and the creation of public policies supportive of health(WHO, 1986). Harm reduction is an exemplar of mainstream public health intervention.

Harm reduction as mainstream drug policy in EuropeEuropean intergovernmental collaboration and information exchange in the drugs field datesback to the early 1970s. While drug policy in the European Union (EU) remains primarily theresponsibility of the Member States, cooperation in matters of drug policy between EUcountries increased over the 1990s, resulting in the adoption of a joint EU drugs strategy aswell as the elaboration of detailed action plans (MacGregor and Whiting, 2010).The EU drugs strategy aims at making ‘a contribution to the attainment of a high level of healthprotection, well-being and social cohesion by complementing the Member States’ action inpreventing and reducing drug use, dependence and drug-related harm to health and society’and at ‘ensuring a high level of security for the general public’ (Council of the European Union,2004, p. 5). For over a decade, EU drug action plans have given priority to preventing the20

Chapter 1: Harm reduction and the mainstream

transmission of infectious disease and reducing drug-related deaths among drug usingpopulations. In a Recommendation adopted by the European Council of 18 June 2003 on the‘prevention and reduction of health-related harm associated with drug dependence’ (Council ofthe European Union, 2003), a framework for action is outlined to assist Member States todevelop strategies to reduce and prevent drug-related harm through the implementation ofharm reduction services for problem drug users. The Recommendation seeks to reduce thenumber of drug-related deaths and extent of health damage, including that related to HIV,hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV) and tuberculosis (TB). These aims are reiterated in thepriorities of the current EU drugs strategy 2005–12 related to demand reduction, aiming at the‘measurable reduction’ of drug use, dependence and drug-related health and social riskthrough a package of interventions combining harm reduction, treatment and rehabilitation,and which emphasise the need to enhance both the ‘quality’ and ‘effectiveness’ of services.Under the responsibility of the EU Commission, progress reviews of the implementation of theEU drugs action plans are carried out with the Member States and additional studies arecommissioned to assess broader policy aspects. Such studies suggest a growing emphasisplaced upon demand and harm reduction in national drug policies in the EU (van derGouwe et al., 2006; European Commission, 2002, 2006, 2008, 2009). The reduction ofdrug harms thus features as a public health objective of all EU Member States (van derGouwe et al., 2006; Cook et al., 2010; MacGregor and Whiting, 2010), with a trend inEurope towards the ‘growth and consolidation of harm reduction measures’ (EMCDDA,2009a, p. 31). The European Commission has noted ‘a process of convergence’ in the drugpolicy adopted by Member States and, as a consequence, increased evidence of ‘policyconsistency’ across the region (European Commission, 2008, p. 67). This convergencetowards harm reduction in drug policy in Europe has been described as the ‘commonposition’ (Hedrich et al., 2008, p. 513).The ‘mainstreaming’ of harm reduction is also evidenced by its transference acrosssubstances, including those causing the greatest burden of global health harm at apopulation level, such as alcohol and tobacco (Rehm et al., 2009; Mathers and Loncar,2006; Rehm and Fischer, 2010; Room, 2010). While the adoption of harm reductionmeasures in relation to tobacco is relatively developmental (Sweanor et al., 2007; Gartner etal., 2010), alcohol harm reduction has a long tradition and is a core feature of alcohol policyin many countries (Robson and Marlatt, 2006; Herring et al., 2010). Harm reduction mayalso feature as a stratagem of public health intervention in relation to cannabis, recreationaland stimulant drug use (Hall and Fischer, 2010; Fletcher et al., 2010; Grund et al., 2010).

Global drug control and harm reductionA recent EU Commission study on global illicit drug markets found no evidence that the globaldrug problem had been reduced in the past decade, but judged that the enforcement of drugprohibition had caused substantial unintended harms (European Commission, 2009). Thislatter finding was shared by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in anevaluation of a century of international drug control efforts 1909–2009 (UNODC, 2009). Thereport clarifies that public health was the driving concern behind drug control, the21

Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges

fundamental objective of the international drug control conventions being to limit the licit tradein narcotic drugs to medical requirements. It states: ‘Public health, the first principle of drugcontrol, has receded from that position, over-shadowed by the concern with public security’,and that ‘looking back over the last century, one can see that the control system and itsapplications have had several unintended consequences’ (UNODC, 2009, pp. 92–3), amongthem the emergence or growth of illicit drug markets, and a ‘policy displacement’ to investingin law enforcement responses, with a corresponding lack of investment in tackling the publichealth harms of drug use. International drug control is framed by three major UN drugtreaties (of 1961, 1971 and 1988), which encourage UN Member States to develop nationalpolicies based on strict law enforcement (Bewley-Taylor, 2004; Wood et al., 2009). There is anincreased momentum, contextualised by a ‘preponderance of evidence’, in support ofrecognising that the current international drug control framework is associated with multiplehealth and social harms, and that these iatrogenic effects can include the exacerbation of HIVepidemics among injecting drug users (IDUs) (Wood et al., 2009, p. 990).Agencies within the UN system have recently re-focused their attention on the primacy ofpublic health, embracing harm reduction interventions as part of a balanced approach withcomplementarity to prevention and treatment interventions. In December 2005, the UnitedNations (UN) General Assembly adopted a resolution encouraging global actions towards‘scaling-up HIV prevention, treatment, care and support with the aim of coming as close aspossible to the goal of universal access to treatment by 2010 for all those who need it’(United Nations General Assembly, 2006). This led to the development of the WHO, UNODCand United Nations Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) joint technical guide forcountries on target setting for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care forinjecting drug users, and focused advocacy efforts on the need for greater coverage towards‘universal access’ (Donoghoe et al., 2008; WHO et al., 2009; ECOSOC, 2009). Scaling-upaccess to, and achieving adequate coverage of, a ‘comprehensive package’ of harmreduction for problem drug users is a major driver of current global drug policy initiatives(WHO, 2009; Ball, 2010; Atun and Kazatchkine, 2010).

Harm reduction as a ‘combination intervention’As a ‘combination intervention’, harm reduction comprises a package of interventionstailored to local setting and need, including access to drug treatment. In reducing the harmsof drug injecting, for example, a harm reduction package may combine OST, NSPs, DCRsand counselling services with peer interventions as well as actions to lobby for policy change.Envisaging harm reduction as a combination intervention is not merely pragmatic and borneout of need, but is also evidence-based. Evidence points towards the enhanced impact ofharm reduction services when they work in combination. Cohort and modelling studies haveshown that the impact of NSP and OST on reduced incidence of infectious disease amongIDUs can be minimal if delivered as ‘stand-alone’ interventions but are markedly moreeffective when delivered in combination, with sufficient engagement among participants toboth (Van Den Berg et al., 2007). This may be especially the case in reducing the incidenceof HCV among IDUs (Hickman, 2010). While epidemiological studies associate NSP and OST22

Chapter 1: Harm reduction and the mainstream

with reduced HIV risk and transmission (Gibson et al., 2001; Wodak and Cooney, 2005;Farrell et al., 2005; Institute of Medicine, 2007; Palmateer et al., 2010; Kimber et al., 2010),the evidence for these interventions impacting on HCV risk and transmission is more modest(Muga et al., 2006; Wright and Tompkins, 2006; Hallinan et al., 2004; Goldberg et al.,2001; Palmateer et al., 2010; Kimber et al., 2010). To date, there is only one European studyshowing that ‘full participation’ across combined harm reduction interventions (NSP andOST) can reduce HIV incidence (by 57 %)andHCV incidence (by 64 %) (van den Berg et al.,2007). A recent cohort study in the United Kingdom also links OST with statistically significantreductions in the incidence of HCV (Craine et al., 2009). Findings noting the enhanced effectof OST in combination with NSP on reduced HIV and HCV incidence among IDUs haveparticular relevance for countries experiencing explosive outbreaks of infectious disease.Just as the effectiveness of NSP and OST services may be enhanced when combined, there isan ‘enhanced impact’ relationship between participation in OST and adherence to HIVtreatment and care among IDUs (Malta et al., 2008; Palepu et al., 2006; Lert andKazatchkine, 2007). There is a potential HIV prevention effect derived from maximisingaccess to HIV treatment (Ball, 2010; Montaner et al., 2006). Similarly, low-threshold access toHIV testing is an important combinative component of harm reduction. In the EU, there is aconsiderable level of homogeneity in policy priorities regarding measures to limit the spreadof infectious diseases among drug users, with NSP being offered either in combination withvoluntary testing and counselling for infectious disease, or in combination with thedissemination of information, education and communication materials (EMCDDA, 2009a, p.83; EMCDDA, 2009c). Evidence also suggests an enhanced impact relationship betweenhepatitis C treatment and access to drug treatment and social support services (Grebely etal., 2007; Birkhead et al., 2007). Additionally, the integration of HIV treatment services withTB treatment and prevention services is a critical feature in determining health outcomes inpeople living with HIV (Sylla et al., 2007), especially in transitional Europe, which is‘especially severely affected’ by TB drug resistance among drug using populations (WHO etal., 2008). Moreover, in HIV prevention there may be combined intervention effects resultingfrom sexual risk reduction being delivered alongside harm reduction (Lindenburg et al.,2006; Copenhaver et al., 2006). Harm reduction integrates with treatment and care in acombined intervention approach (Ball, 2010).

Harm reduction and ‘enabling environments’ for healthA fundamental tenet of public health intervention is to create environments conducive toindividual and community risk avoidance, including through the creation and maintenance ofpublic policies supportive of health (WHO, 1986). The continuum of ‘combinationinterventions’ available to harm reduction extends from drug prevention and treatmentthrough to policy reform and the removal of structural barriers to protecting the rights of allto health. WHO makes specific recommendation for ‘laws that do not compromise access toHIV services for drug users through criminalisation and marginalisation’ (Ball, 2007). If publicpolicies or laws generate harm then these too fall within the scope of the combination ofinterventions that make up harm reduction. Structural interventions for public health seek toremove contextual or environmental barriers to risk and harm reduction while enabling social23

Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges

and environmental conditions that protect against risk and vulnerability (Blankenship et al.,2006). The delineation of the ‘risk environment’ surrounding the production of drug harms indifferent settings has led to the identification of structural interventions with the potential forencouraging community-level change (Rhodes, 2002, 2009).Of critical concern — as evidenced by multiple studies in multiple settings — is how the legalenvironment can constrain risk avoidance and promote harm among problem drug users,especially among people who inject drugs (Small et al., 2006; Rhodes, 2009; Kerr et al.,2005). In some settings, intense street-level police surveillance and contact can be associatedwith reluctance among IDUs to carry sterile needles and syringes for fear of arrest, caution, fineor detention (Rhodes et al., 2003; Cooper et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2008). Evidence associateselevated odds of syringe sharing with increased police contact (Rhodes et al., 2004),confiscation of injecting equipment (Werb et al., 2008), and rates of arrest (Pollini et al., 2008),yet rates of arrest can show no deterrent effect on levels of injecting (Friedman et al., 2010).High-visibility policing, and police ‘crackdowns’, have been linked to the interruption of saferinjecting routines, leading to safety ‘short-cuts’ or hasty injections, exacerbating the risk of viraland bacterial infections as well as overdose (Blakenship and Koester, 2002; Bluthenthal et al.,1999; Small et al., 2006). Such policing practices may displace drug users geographically,disrupt social networks of support, contribute to the stigmatisation of drug use, and limit thefeasibility, coverage and impact of public health responses (Burris et al., 2004; Davis et al.,2005; Friedman et al., 2006; Broadhead et al., 1999). In turn, prison and incarceration arelinked to elevated odds of HIV transmission among people who use drugs (Dolan et al., 2007;Jürgens et al., 2009; Stevens et al., 2010).Harm reduction may therefore include interventions that seek to reduce the harms generatedby drug and other public policies, including through policy reform and legal change. Forinstance, as Room (2010, p. 110) notes: ‘If the harm arises from heavy use per se, reducingor eliminating use or changing the mode of use are the logical first choices for reducing theharm. But if the harm results from the criminalisation per se, decriminalising is a logical wayof reducing the harm.’ WHO also notes that ‘the alignment of drug control measures withpublic health goals [is] a priority’ (Ball, 2007, p. 687). It is therefore important to note thepotential public health gains of engaging policing and criminal justice agencies as part oflocal public health partnerships, including in the delivery of harm reduction interventions incommunity and closed settings (see Stevens et al., 2010).

Coverage and scale-up2010 is the year for achieving the UN General Assembly target of ‘near universal access’ toHIV prevention, treatment and care for populations affected by HIV. In Europe, considerableprogress has been made towards achieving greater coverage of harm reduction services forIDUs (see Cook et al., 2010). Every EU Member State has one or more needle and syringeprogrammes (EMCDDA, 2009a). Pharmacy-based NSPs operate in at least 12 MemberStates. All Member States provide opioid substitution treatment for those with opioiddependence (EMCDDA, 2009a). An estimated 650,000 people were receiving OST inEurope in 2007, though large national variations in coverage exist (EMCDDA, 2009a).24

Chapter 1: Harm reduction and the mainstream

Evidence suggests coverage is an important determinant of drug-related risk and harm. In arecent comparison of the incidence of diagnosed HIV among IDUs and the coverage of OSTand NSP in the EU and five other middle- and high-income countries, those countries withgreatest provision of both OST and NSP in 2000 to 2004 had lower HIV incidence in 2005and 2006 (Wiessing et al., 2009). In this study, the availability and coverage of harmreduction measures was considerably lower in Russia and Ukraine where the incidence ofHIV was considerably higher when compared to Western European countries. Whereas HIVtransmission rates are stabilising or decreasing in most of Western and Central Europe, theyare increasing in the Eastern part of the continent, outside the EU, where harm reductionservices are ‘insufficient and need to be reinforced’ (Wiessing et al., 2008).Coverage of harm reduction interventions is variable within the EU. While recent estimates ofthe total number of OST clients represent around 40 % of the estimated total number ofproblem opiate users in the EU, the level of provision is far from uniform across the region.Estimates of coverage from 10 countries where such data are available range from below5 % to over 50 % of opioid users covered by OST (EMCDDA, 2009e).European trends in the provision of NSP between 2003 and 2007 show a 33 % increase inthe number of syringes distributed through specialised programmes, with steady increasesin most countries, except several countries in northern and central Europe (EMCDDA,2009d). Although country-specific coverage estimates of NSP are scarce, the number ofsyringes distributed by specialist NSPs per estimated IDU per year seems to vary widelybetween countries (EMCDDA, 2010). European-level estimates suggest that on averagesome 50 syringes are distributed per estimated IDU per year across the EU (Wiessing et al.,2009). Overall availability of sterile syringes is also dependent upon pharmacy provision, inturn influenced by legislation, regulations, and pricing, as well as by the attitudes ofpharmacists.In its evaluation of the EU drug action plan, the European Commission emphasised that the‘availability and accessibility of [harm reduction] programmes are still variable among theMember States’ and that ‘further improvements are still needed in [the] accessibility,availability and coverage’ of services (European Commission, 2008, p. 66). In the Europeanregion more generally, scaling up comprehensive service provision is a priority, withstrengthening health systems, engaging civil society, and securing political commitment forharm reduction considered key determinants to effective scale-up (Atun and Kazatchkine,2010). There is then considerable variability in how harm reduction is enacted in policy andeven more so in practice, as well as resistance to the mainstreaming of harm reduction insome settings. Understanding the failure to implement evidence-based programmes andpolicies has been identified as a major topic for future research (Des Jarlais and Semaan,2009). In countries where heroin epidemics are recent and rates of HIV infection among drugusers low, implementation of harm reduction measures such as NSP or OST may beperceived by some as difficult to justify. This may be especially so in the context of finite andretracting economic resources in the health sector. Evidence, however, indicates the cost-effectiveness of the introduction and scale-up of harm reduction (Zaric et al., 2000; NationalCentre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research UNSW, 2009).25

Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges

Voices of resistance to the mainstreaming of harm reduction in drug policy can be foundwithin the EU (see MacGregor and Whiting, 2010), but are most vociferous within thebroader European region, and especially Russia, which today has one of the largestepidemics of HIV associated with drug injecting in the world, has a policy that places strongemphasis on law enforcement, prohibits the introduction of OST and limits the developmentof NSP and other harm reduction interventions to adequate scale (Sarang et al., 2007;Human Rights Watch, 2007; Elovich and Drucker, 2008).

Evidence, impacts and challengesAn effective harm reduction policy, programme or intervention is one that ‘can bedemonstrated, to a reasonable and informed audience, by direct measurement or otherwise,that on balance of probabilities has, or is likely to result in, a net reduction in drug-relatedharm’ (Lenton and Single, 2004, p. 217). This monograph aims to reflect upon over twodecades of harm reduction research, evidence and impact in Europe and beyond.There are now multiple systematic and other reviews of the scientific evidence in support ofdifferent harm reduction interventions, especially in the context of HIV, hepatitis C andinjecting drug use (Wodak and Cooney, 2005; Farrell et al., 2005; Institute of Medicine,2007; Palmateer et al., 2010). Chapters in this monograph take stock of such evidence inEuropean perspective, including regarding the effectiveness of interventions to prevent HIVand HCV among injecting drug users (Chapter 5 — Kimber et al., 2010), the role of DCRs(Chapter 11 — Hedrich et al., 2010), the effect of epidemiological setting on interventionimpact (Chapter 6 — Vickerman and Hickman, 2010) and the implications that variations indrug use patterns have on harm reduction interventions (Chapter 15 — Hartnoll et al., 2010).While diffusing throughout Europe primarily in response to health harms linked to injectingdrug use (Chapter 2 — Cook et al., 2010; Chapter 3 — MacGregor and Whiting, 2010),harm reduction approaches have mainstream applicability. Chapters consider the specificchallenges of harm reduction interventions and policies regarding alcohol (Chapter 10 —Herring et al., 2010), tobacco (Chapter 9 — Gartner et al., 2010), cannabis (Chapter 8 —Hall and Fischer, 2010), recreational drug use among young people (Chapter 13 — Fletcheret al., 2010), and stimulants (Chapter 7 — Grund et al., 2010). The potential role — oftenunrealised — of drug user engagement and criminal justice interventions are also discussed(Chapter 12 — Hunt et al., 2010; Chapter 14 — Stevens et al., 2010). Taken together, thismonograph seeks to synthesise, as well as critically appraise, evidence of the impacts andchallenges of harm reduction interventions and policies in Europe and beyond.Harm reduction, like any public policy, is inevitably linked to political debate, and it is naiveto assume otherwise, but it is precisely because of this that it is imperative that interventionsare also developed upon evidence-based argument and critique. Europe is experiencingsignificant political change, which in 2004 enabled the most extensive wave of EuropeanUnion enlargement ever seen. Following the ratification of the Lisbon Treaty by all 27Member States in 2009, the importance of the Union as a major political player in the regionwill grow. Among the new challenges to be faced is maintaining a strong public healthposition in controlling and preventing HIV and HCV epidemics linked to drug use. This may26

Chapter 1: Harm reduction and the mainstream

be in a context of harsher economic conditions as well as increased migration, includingfrom countries with large HIV epidemics driven by drug injecting and where evidence-basedharm reduction measures are not always met with political commitment. The relative successof harm reduction strategies adopted in many European countries over the past two decades,and the evidence gathered in their support, provides a framework for the development,expansion and evaluation of harm reduction across multiple forms of substance use.

ReferencesNote: publications with three or more authors are listed chronologically, to facilitate the location of ‘et al.’references.Ashton, J. and Seymour, H. (1988),The new public health,Open University Press, Milton Keynes.Atun, R. and Kazathckine, M. (2010), ‘Translating evidence into action: challenges to scaling up harm reductionin Europe and Central Asia’, in Chapter 4, ‘Perspectives on harm reduction: what experts have to say’, inEuropean Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts andchallenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of theEuropean Union, Luxembourg.Ball, A. (2007), ‘HIV, injecting drug use and harm reduction: a public health response’,Addiction102, pp. 684–90.Ball, A. (2010), ‘Broadening the scope and impact of harm reduction for HIV prevention, treatment and careamong injecting drug users’, in Chapter 4, ‘Perspectives on harm reduction: what experts have to say’, inEuropean Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts andchallenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of theEuropean Union, Luxembourg.Bellis, D. J. (1981),Heroin and politicians: the failure of public policy to control addiction in America,GreenwoodPress, Westport, CT.Bewley-Taylor, D. (2004), ‘Harm reduction and the global drug control regime: contemporary problems andfuture prospects’,Drug and Alcohol Review23, pp. 483–9.Birkhead, G. S., Klein, S. J., Candelas, A. R., et al. (2007), ‘Integrating multiple programme and policyapproaches to hepatitis C prevention and care for injection drug users: a comprehensive approach’,InternationalJournal of Drug Policy18, pp. 417–25.Blankenship, K. M. and Koester, S. (2002), ‘Criminal law, policing policy, and HIV risk in female street sexworkers and injection drug users’,Journal of Law and Medical Ethics30, pp. 548–59.Blankenship, K. M., Friedman, S. R., Dworkin, S. and Mantell, J. E. (2006), ‘Structural interventions: concepts,challenges and opportunities for research’,Journal of Urban Health83, pp. 59–72.Bluthenthal, R. N., Lorvick J., Kral A. H., Erringer, E. A. and Kahn, J. G. (1999), ‘Collateral damage in the war ondrugs: HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users’,International Journal of Drug Policy10, pp. 25–38.Broadhead, R. S., Van Hulst, Y. and Heckathorn, D. D. (1999), ‘Termination of an established syringe-exchange:a study of claims and their impact’,Social Problems46, pp. 48–66.Burris, S., Donoghoe, M., Blankenship, K., et al. (2004), ‘Addressing the “risk environment” for injection drugusers: the mysterious case of the missing cop’,Milbank Quarterly82, pp. 125–56.Cooper, H., Moore, L., Gruskin, S. and Krieger, N. (2005), ‘The impact of a police drug crackdown on druginjectors’ ability to practice harm reduction’,Social Science and Medicine61, pp. 673–84.

27

Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges

Cook, C., Bridge, J. and Stimson, G. V. (2010), ‘The diffusion of harm reduction in Europe and beyond’, inEuropean Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts andchallenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of theEuropean Union, Luxembourg.Copenhaver, M., Johnson, B., Lee, I-C., et al. (2006), ‘Behavioral HIV risk reduction among people who injectdrugs: meta-analytic evidence of efficacy’,Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment31, pp. 163–71.Council of the European Union (2003), ‘Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003 on the prevention andreduction of health-related harm associated with drug dependence (2003/488/EC)’. Available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32003H0488:EN:HTML.Council of the European Union (2004),EU drugs strategy (2005–2012),CORDROGUE 77, 22 November 2004.Available at http://ec.europa.eu/justice_home/doc_centre/drugs/strategy/doc_drugs_strategy_en.htm.Craine, N., Hickman, M., Parry, J. V., et al. (2009), ‘Incidence of hepatitis C in drug injectors: the role ofhomelessness, opiate substitution treatment, equipment sharing, and community size’,Epidemiology and Infection137, pp. 1255–65.Davis, C., Burris, S., Metzger, D., Becjer, J. and Lunch, K. (2005), ‘Effects of an intensive street-level policeintervention on syringe exchange program utilization’,American Journal of Public Health95, pp. 223–36.Des Jarlais, D. C. (1995), ‘Harm reduction: a framework for incorporating science into drug policy’,AmericanJournal of Public Health85, pp. 10–12.Des Jarlais, D. C. and Semaan, S. (2009), ‘HIV prevention and psychoactive drug use: a research agenda’,Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health63, pp. 191–6.Des Jarlais, D. C., Perlis, T., Arasteh, K., et al. (2005), ‘Reductions in hepatitis C virus and HIV infections amonginjecting drug users in New York City’,AIDS19 (Supplement 3), pp. S20–5.Dolan, K., Kite, B., Aceijas, C., and Stimson, G. V. (2007), ‘HIV in prison in low income and middle incomecountries’,Lancet Infectious Diseases7, pp. 32–43.Donoghoe, M., Verster, A., Pervilhac, C. and Williams, P. (2008), ‘Setting targets for universal access to HIVprevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users (IDUs): towards consensus and improved guidance’,International Journal of Drug Policy19 (Supplement 1), pp. S5–14.ECOSOC (UN Economic and Social Council) (2009), ‘Economic and Social Council resolution E/2009/L.23adopted by the Council on 24 July 2009: Joint United Nations Programme on Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (UNAIDS)’. Available at http://www.un.org/Docs/journal/asp/ws.asp?m=E/2009/L.23.Elovich, R. and Drucker, E. (2008), ‘On drug treatment and social control: Russian narcology’s great leapbackwards’,Harm Reduction Journal5, p. 23. DOI: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-23.EMCDDA (2009a),Annual report 2009: the state of the drugs problem in Europe,European Monitoring Centre forDrugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.EMCDDA (2009b),Drug offences: sentencing and other outcomes,European Monitoring Centre for Drugs andDrug Addiction, Lisbon.EMCDDA (2009c), Statistical bulletin, Table HSR-6, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction,Lisbon. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats09/hsrtab6.EMCDDA (2009d), Statistical bulletin, Table HSR-5, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction,Lisbon. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats09/hsrtab5.

28

Chapter 1: Harm reduction and the mainstream

EMCDDA (2009e), Statistical bulletin, Figure HSR-1, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction,Lisbon. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats09/hsrfig1.EMCDDA (2010),Injecting drug use in Europe,European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon.Erickson, P. (1999), ‘Introduction: the three phases of harm reduction. An examination of emerging concepts,methodologies, and critiques’,Substance Use and Misuse34 (1), pp. 1–7.European Commission (2002),Implementation of EU-action plan on drugs 2000–2004: progress review for theMember States.Available at http://ec.europa.eu/justice_home/doc_centre/drugs/studies/doc/review_actplan_02_04_en.pdf.European Commission (2006),2006 progress review on the implementation of the EU drugs action plan (2005–2008),Commission Staff Working Document SEC (2006) 1803. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/justice_home/doc_centre/drugs/strategy/doc/sec_2006_1803_en.pdf.European Commission (2008),The report of the final evaluation of the EU drugs action plan 2005–2008,CommissionStaff Working Document (accompanying document to the Communication from the Commission to the Council andthe European Parliament on an EU drugs action plan 2009–2012) COM (2008) 567, SEC(2008) 2456. Availableat http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/drug/documents/COM2008_0567_a1_en.pdf.European Commission (2009),Report on global illicit drug markets, 2009.Available at http://ec.europa.eu/justice_home/doc_centre/drugs/studies/doc_drugs_studies_en.htm.Farrell, M., Gowing, L., Marsden, J., Ling, W. and Ali, R. (2005), ‘Effectiveness of drug dependence treatment inHIV prevention’,International Journal of Drug Policy16 (Supplement 1), pp. S67–75.Fletcher, A., Calafat, A., Pirona, A. and Olszewski, D. (2010), ‘Young people, recreational drug use and harmreduction’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence,impacts and challenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, PublicationsOffice of the European Union, Luxembourg.Friedman, S. R., Cooper, H. L. F., Tempalski, B., et al. (2006), ‘Relationships between deterrence and lawenforcement and drug-related harm among drug injectors in U.S. metropolitan cities’,AIDS20, pp. 93–9.Friedman, S. R., Pouget, E. R., Chatterjee, S., et al. (2010), ‘Do drug arrests deter injection drug use?’ (in press).Gartner, C., Hall, W. and NcNeill, A. (2010), ‘Harm reduction policies for tobacco’, in European MonitoringCentre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges,Rhodes, T.and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the European Union,Luxembourg.Gibson, D. R., Flynn, N. and Perales, D. (2001), ‘Effectiveness of syringe exchange programs in reducing HIV riskbehavior and HIV seroconversion among injecting drug users’,AIDS15, pp. 1329–41.Goldberg, D., Burns, S., Taylor, A., et al. (2001), ‘Trends in HCV prevalence among injecting drug users inGlasgow and Edinburgh during the era of needle/syringe exchange’,Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases33, pp. 457–61.Grebely, J., Genoway, K., Khara, M., et al. (2007), ‘Treatment uptake and outcomes among current and formerinjection drug users receiving directly observed therapy within a multidisciplinary group model for the treatmentof hepatitis C virus infection’,International Journal of Drug Policy18: 437–43.Grund, J-P., Coffin, P., Jauffret-Roustide, M., et al. (2010), ‘The fast and furious: cocaine, amphetamines and harmreduction’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence,impacts and challenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, PublicationsOffice of the European Union, Luxembourg.

29

Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges

Hall, W. and Fischer, B. (2010), ‘Harm reduction policies for cannabis’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugsand Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D.(eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.Hallinan, R., Byrne, A., Amin, J. and Dore, G. J. (2004), ‘Hepatitis C virus incidence among injecting drug userson opioid replacement therapy’,Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health28, pp. 576–8.Hartnoll, R., Gyarmarthy, A. and Zabransky, T. (2010), ‘Variations in problem drug use patterns and theirimplications for harm reduction’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harmreduction: evidence, impacts and challenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No.10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.Hedrich, D., Pirona, A. and Wiessing, L. (2008), ‘From margins to mainstream: the evolution of harm reductionresponses to problem drug use in Europe’,Drugs: education, prevention and policy15, pp. 503–17.Hedrich, D., Kerr, T. and Dubois-Arber, F. (2010), ‘Drug consumption facilities in Europe and beyond’, inEuropean Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts andchallenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of theEuropean Union, Luxembourg.Herring, R., Thom, B., Beccaria, F., Kolind, T. and Moskalewicz, J. (2010), ‘Alcohol harm reduction in Europe’, inEuropean Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts andchallenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of theEuropean Union, Luxembourg.Hickman, M. (2010), ‘HCV prevention: a challenge for evidence-based harm reduction’, in Chapter 4,‘Perspectives on harm reduction: what experts have to say’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and DrugAddiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds),Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.Human Rights Watch (2007),Rehabilitation required: Russia’s human rights obligation to provide evidence-baseddrug dependence treatment,Human Rights Watch, New York.Hunt, N., Albert, E. and Montañés Sánchez, V. (2010), ‘User involvement and user organising in harm reduction’,in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts andchallenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of theEuropean Union, Luxembourg.Institute of Medicine (2007),Preventing HIV infection among injecting drug users in high-risk countries: an assessmentof the evidence,National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC.International Drug Policy Consortium (2009),The 2009 Commission on Narcotic Drugs and its high level segment:report of proceedings,Briefing Paper, IDPC, London.Jürgens, R., Ball, A. and Verster, A. (2009), ‘Interventions to reduce HIV transmission related to injecting drug usein prison’,Lancet Infectious Diseases9, pp. 57–66.Kerr, T., Small, W. and Wood, E. (2005), ‘The public health and social impacts of drug market enforcement: areview of the evidence’,International Journal of Drug Policy16, pp. 210–20.Kimber, J., Palmateer, N., Hutchinson, S., et al. (2010), ‘Harm reduction among injecting drug users: evidence ofeffectiveness’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction:evidence, impacts and challenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10,Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.Lancet(2009), ‘The future of harm reduction programmes in Russia’,Lancet374, p. 1213.

30

Chapter 1: Harm reduction and the mainstream

Lenton, S. and Single, E. (2004), ‘The definition of harm reduction’,Drug and Alcohol Review17, pp. 213–20.Lert, F. And Kazatchkine, M. (2007), ‘Antiretroviral HIV treatment and care for injecting drug users: an evidence-based overview’,International Journal of Drug Policy18, 255–61.Lindenburg, C. E. A., Krol, A., Smit, C., et al. (2006), ‘Decline in HIV incidence and injecting, but not in sexualrisk behaviour, seen in drug users in Amsterdam’,AIDS20, pp. 1771–5.MacGregor, S. and Whiting, M. (2010), ‘The development of European drug policy and the place of harmreduction within this’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction:evidence, impacts and challenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10,Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.Malta, M., Strathdee, S., Magnanini, M., et al. (2008), ‘Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV among drugusers: a systematic review’,Addiction103, pp. 1242–57.Mathers, C. D. and Loncar, D. (2006), ‘Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to2030’,PLoS Medicine3, pp. 2011–30.Miller, C., Firestone, M., Ramos, R., et al. (2008), ‘Injecting drug users’ experiences of policing practices in twoMexican–U.S. border cities’,International Journal of Drug Policy19, pp. 324–31.Montaner, J. S., Hogg, R., Wood, E., et al. (2006), ‘The case for expanding access to highly active antiretroviraltherapy to curb the growth of the HIV epidemic’,Lancet368, 531–6.Muga, R., Sanvisens, A., Bolao, F., et al. (2006), ‘Significant reductions of HIV prevalence but not of hepatitis Cvirus infections in injection drug users from metropolitan Barcelona: 1987–2001’,Drug and Alcohol Dependence82, Supplement 1, pp. S29–33.National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research UNSW (2009),Return on investment 2: evaluating thecost-effectiveness of needle and syringe programs in Australia 2009,Australian Government Department for Healthand Ageing. Available at http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/needle-return-2.Palepu, A., Tyndall, M. W., Joy, R., et al. (2006), ‘Antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes amongHIV/HCV co-infected injection drug users: the role of methadone maintenance therapy’,Drug and AlcoholDependence84, pp. 188–94.Palmateer, N., Kimber, J., Hickman, M., et al. (2010), ‘Preventing hepatitis C and HIV transmission amonginjecting drug users: a review of reviews’,Addiction,in press.Peterson, A. and Lupton, D. (1996),The new public health: health and self in the age of risk,Sage Publications,Newbury Park, CA.Pollini, R. A., Brouwer, K. C., Lozada, R. M., et al. (2008), ‘Syringe possession arrests are associated withreceptive syringe sharing in two Mexico–U.S. border cities’,Addiction103, pp. 101–08.Rehm, J., Mathers, C., Popova, S., et al. (2009), ‘Global burden of disease and injury and economic costattributable to alcohol and alcohol-use disorders’,Lancet373, pp. 2223–32.Rehm, J., Fischer, B., Hickman, M., et al. (2010), ‘Perspectives on harm reduction: what experts have to say’, inEuropean Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts andchallenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of theEuropean Union, Luxembourg.Rhodes, T. (2002), ‘The “risk environment”: a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm’,International Journal of Drug Policy13, pp. 85–94.

31

Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges

Rhodes, T. (2009), ‘Risk environments and drug harms: a social science for harm reduction approach’,International Journal of Drug Policy20, pp. 193–201.Rhodes, T., Mikhailova, L., Sarang, A., et al. (2003), ‘Situational factors influencing drug injecting, risk reductionand syringe exchange in Togliatti City, Russian Federation: a qualitative study of micro risk environment’,SocialScience and Medicine57, pp. 39–54.Rhodes, T., Judd, A., Mikhailova, L., et al. (2004), ‘Injecting equipment sharing among injecting drug users inTogliatti City, Russian Federation: maximising the protective effects of syringe distribution’,Journal of AcquiredImmune Deficiency Syndromes35, pp. 293–300.Robson, G. and Marlatt, G. (2006), ‘Harm reduction and alcohol policy’,International Journal of Drug Policy17,pp. 255–7.Room, R. (2010), ‘The ambiguity of harm reduction: goal or means, and what constitutes harm?’, in Chapter 4,‘Perspectives on harm reduction: what experts have to say’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and DrugAddiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds),Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.Sarang, A., Rhodes, T., Platt, L., et al. (2006), ‘Drug injecting and syringe use in the HIV risk environment ofRussian penitentiary institutions’,Addiction101, pp. 1787–96.Sarang, A., Stuikyte, R. and Bykov, R. (2007), ‘Implementation of harm reduction in Central and Eastern Europeand Central Asia’,International Journal of Drug Policy18, pp. 129–35.Sarang, A., Rhodes, T. and Platt, L. (2008), ‘Access to syringes in three Russian cities: implications for syringedistribution and coverage’,International Journal of Drug Policy19, pp. S25–S36.Small, W., Kerr, T., Charette, J., Schechter, M. T. and Spittal, P. M. (2006), ‘Impacts of intensified police activityon injection drug users: evidence from an ethnographic investigation’,International Journal of Drug Policy17, pp.85–95.Spear, B. (1994), ‘The early years of the “British System” in practice’, in Strang, J. and Gossop, M. (eds)Heroinaddiction and drug policy,Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 3–28.Stevens, A., Stöver, H. and Brentari, C. (2010), ‘Criminal justice approaches to harm reduction in Europe’, inEuropean Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harm reduction: evidence, impacts andchallenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No. 10, Publications Office of theEuropean Union, Luxembourg.Sweanor, D., Alcabes, P. and Drucker, E. (2007), ‘Tobacco harm reduction: how rational public policy couldtransform a pandemic’,International Journal of Drug Policy,18, pp. 70–4.Sylla, L., Douglas Bruce, R., Kamarulzaman, A. and Altice, F. L. (2007), ‘Integration and co-location of HIV/AIDS,tuberculosis and drug treatment services’,International Journal of Drug Policy18, pp. 306–12.United Nations Development Program (2008),Living with HIV in Eastern Europe and the CIS,UNDP, Bratislava.United Nations General Assembly Sixtieth Special Session (2006),Political declaration on HIV/AIDS.Resolution60/262 adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, United Nations, New York.UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) (2009),A century of international drug control,UNODC,Vienna. Available at http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Studies/100_Years_of_Drug_Control.pdf.van den Berg, C., Smit, C., Van Brussel, G., Coutinho, R. A. and Prins, M. (2007), ‘Full participation in harmreduction programmes is associated with decreased risk for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus:evidence from the Amsterdam cohort studies among drug users’,Addiction102, pp. 1454–62.

32

Chapter 1: Harm reduction and the mainstream

van der Gouwe, D., Gallà, M., Van Gageldonk, A., Croes, E., Engelhardt, J., Van Laar, M. and Buster, M.(2006),Prevention and reduction of health-related harm associated with drug dependence: an inventory of policies,evidence and practices in the EU relevant to the implementation of the Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003.Synthesis report. Contract nr. SI2.397049,Trimbos Instituut, Utrecht. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/drug/documents/drug_report_en.pdf.Vickerman, P. and Hickman, M. (2010), ‘The effect of epidemiological setting on the impact of harm reductiontargeting injecting drug users’, in European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA),Harmreduction: evidence, impacts and challenges,Rhodes, T. and Hedrich, D. (eds), Scientific Monograph Series No.10, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.Werb, D., Wood, E., Small, W., et al. (2008), ‘Effects of police confiscation of illicit drugs and syringes amonginjection drug users in Vancouver’,International Journal of Drug Policy19, pp. 332–8.WHO (World Health Organization) (1974),Expert committee on drug dependence: twentieth report,TechnicalReport Series 551, WHO, Geneva.WHO (1986),Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion,WHO, Geneva, WHO/HPR/HEP/95.1.WHO (2009),HIV/AIDS: comprehensive harm reduction package,WHO, Geneva. Available at http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/idu/harm_reduction/en/index.html.WHO, UNODC and UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) (2008),Policy guidelines forcollaborative HIV and TB services for injecting and other drug users,WHO, Geneva. Available at http://www.who.int/tb/publications/2008/en/index.html.WHO, UNODC and UNAIDS (2009), ‘Technical guide for countries to set targets for universal access to HIVprevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users. Available at http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/targetsetting/en/index.html.Wiessing, L., Van de Laar, M.J., Donoghoe, M.C., et al. (2008), ‘HIV among injecting drug users in Europe:increasing trends in the East’,Eurosurveillance3 (50). Available at http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19067.Wiessing, L., Likataviˇ ius, G., Klempová, D., et al. (2009), ‘Associations between availability and coverage ofcHIV-prevention measures and subsequent incidence of diagnosed HIV infection among injection drug users’,American Journal of Public Health99 (6), pp. 1049–52.Wodak, A. and Cooney, A. (2005), ‘Effectiveness of sterile needle and syringe programmes’,InternationalJournal of Drug Policy16, Supplement 1, pp. S31–44.Wolfe, D. and Malinowska-Sempruch, K. (2004),Illicit drug policies and the global HIV epidemic,Open SocietyInstitute, New York.Wood, E., Spittal, P. M., Li, K., et al. (2004), ‘Inability to access addiction treatment and risk of HIV-infectionamong injection drug users’,Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes36, pp. 750–4.Wood, E., Werb, D., Marshall, B., Montaner, J. S. G. and Kerr, T. (2009), ‘The war on drugs: a devastatingpublic-policy disaster’,Lancet373, pp. 989–90.Wright, N. M. and Tompkins, C. N. (2006), ‘A review of the evidence for the effectiveness of primary preventioninterventions for hepatitis C among injecting drug users’,Harm Reduction Journal6 (3), p. 27.Zaric, G. S., Barnett, P. G. and Brandeau, M. L. (2000), ‘HIV transmission and the cost-effectiveness ofmethadone maintenance’,American Journal of Public Health90 (7), pp.1100–11.

33

Background

PARTI

Chapter 2The diffusion of harm reduction in Europe and beyondCatherine Cook, Jamie Bridge and Gerry V. Stimson

AbstractThis chapter traces the diffusion of harm reduction in Europe and around the world. The term‘harm reduction’ became prominent in the mid-1980s as a response to newly discovered HIVepidemics amongst people who inject drugs in some cities. At this time, many European citiesplayed a key role in the development of innovative interventions such as needle and syringeprogrammes. The harm reduction approach increased in global coverage and acceptancethroughout the 1990s and became an integral part of drug policy guidance from theEuropean Union at the turn of the century. By 2009, some 31 European countries supportedharm reduction in policy or practice — all of which provided needle and syringeprogrammes and opioid substitution therapy. Six countries also provided prison needle andsyringe programmes, 23 provided opioid substitution therapy in prisons, and all but two ofthe drug consumption rooms in the world were in Europe. However, models and coveragevary across the European region. Harm reduction is now an official policy of the UnitedNations, and Europe has played a key role in this development and continues to be a strongvoice for harm reduction at the international level.Keywords:history, harm reduction, global diffusion, international policy, Europe.

IntroductionThe term ‘harm reduction’ refers to ‘policies, programmes and practices that aim to reducethe adverse health, social and economic consequences of the use of legal and illegalpsychoactive drugs’, and are ‘based on a strong commitment to public health and humanrights’ (IHRA, 2009a, p. 1). The term came to prominence after the emergence of HIV inEurope and elsewhere in the mid-1980s (Stimson, 2007). However, the underlyingprinciples of this approach can be traced back much further (see box on p. 38). Thischapter seeks to explore the emergence and diffusion of harm reduction from a localised,community-based response to international best practice. Since space restricts anexhaustive history transcending all aspects of harm reduction, we will focus primarily onthe development and acceptance of approaches to prevent HIV transmission amongstpeople who inject drugs. It is these interventions that have come to epitomise the essence ofharm reduction. For the purposes of this chapter, Europe is defined as comprising 33countries — the 27 Member States of the European Union (EU), the candidate countries(Croatia, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Turkey), and Norway,Switzerland and Iceland.37

Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges

Early examples of ‘harm reduction’ principles and practice1912 to 19231926Narcotic maintenance clinics in the United States.Report of the United Kingdom Departmental Committee on Morphine andHeroin Addiction (the Rolleston Committee) concluded in support of opiateprescription to help maintain normality for heroin-dependent patients.Emergence of ‘controlled drinking’ as an alternative to abstinence-basedtreatments for some alcohol users.Grass-roots work on reducing harms connected to the use of LSD, cannabis,amphetamines, and to glue sniffing.

1960s1960s on

The diffusion of harm reduction in EuropeIn 1985 HIV antibody tests were introduced, leading to the discovery of high rates ofinfection in numerous European cities among people who inject drugs — includingEdinburgh (51 %) (Robertson et al., 1986), Milan (60 %), Bari (76 %), Bilbao (50 %), Paris(64 %), Toulouse (64 %), Geneva (52 %) and Innsbruck (44 %) (Stimson, 1995). These localisedepidemics occurred in a short space of time, with 40 % or more prevalence of infectionreached within two years of the introduction of the virus into drug-injecting communities(Stimson, 1994). Analysis of stored blood samples indicated that HIV was first present inAmsterdam in 1981, and in Edinburgh one or two years later (Stimson, 1991). Heroin useand drug injecting in European countries had been on the increase since the 1960s (Hartnollet al., 1989) and research indicated that the sharing of needles and syringes was commonamongst people who injected drugs (Stimson, 1991).It soon became evident that parts of Europe faced a public health emergency (see boxbelow). Across Europe, the response was driven at a city level by local health authorities andcivil society (sometimes in spite of interference from government) (O’Hare, 2007a). In 1984(one year before the introduction of HIV testing), drug user organisations in the Netherlandsstarted to distribute sterile injecting equipment to their peers to counter hepatitis Btransmission (Buning et al., 1990; Stimson, 2007). This is widely acknowledged as the firstformal needle and syringe programme (NSP), although informal or ad hoc NSPs existedaround the world before 1984. Soon after, the Netherlands integrated NSPs within low-threshold centres nationwide (Buning et al., 1990).The transformation brought by HIV and harm reductionHIV and AIDS provide the greatest challenges yet to drug policies and services. Policy-makersand practitioners … have been forced to reassess their ways of dealing with drug problems;this includes clarifying their aims, identifying their objectives and priorities for their work, theirstyles of working and relationships with clients, and the location of the work. Within the spaceof about three years, mainly between 1986 and 1988, there have been major debates aboutHIV, AIDS and injecting drug use. In years to come, it is likely that the late 1980s will beidentified as a key period of crisis and transformation in the history of drugs policy.(Stimson, 1990b)

38

Chapter 2: The diffusion of harm reduction in Europe and beyond

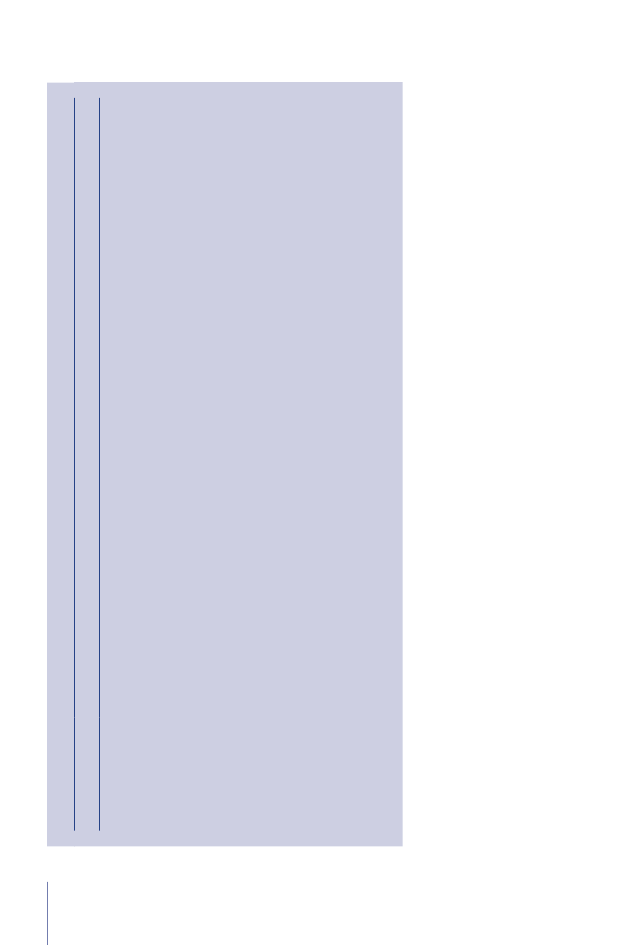

In 1986, parts of the United Kingdom introduced NSPs (Stimson, 1995; O’Hare, 2007b). By1987, similar programmes had also been adopted in Denmark, Malta, Spain and Sweden(Hedrich et al., 2008). By 1990, NSPs operated in 14 European countries, and were publiclyfunded in 12. This had increased to 28 countries by the turn of the century, with public fundssupporting programmes in all but one of these (EMCDDA, 2009a, Table HSR-4). Somecountries were also experimenting with alternative models of distribution, including syringevending machines and pharmacy-based schemes (Stimson, 1989). By the early 1990s, therewas growing evidence of the feasibility of NSPs and in support of the interventions’ ability toattract into services otherwise-hidden populations of people who inject drugs, and reducelevels of syringe sharing (Stimson, 1991).Figure 2.1:Year of introduction of opioid substitution treatment (OST) and official introduction ofneedle and syringe programmes (NSPs) in EU countries

3025201510501965OSTNSP

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

Note: The data represent the official introduction of OST, and the availability of publicly funded NSPs.Source:Reitox national focal points.